THE SCENE: Readings, Happenings, Events, Gallery of Arts

Monday November 17, 2025

A Night of post-Beat Poetry, Beat Poet Memories, and Poetry in the Original San Francisco Tradition with Gerald Nicosia and Ron Myers.

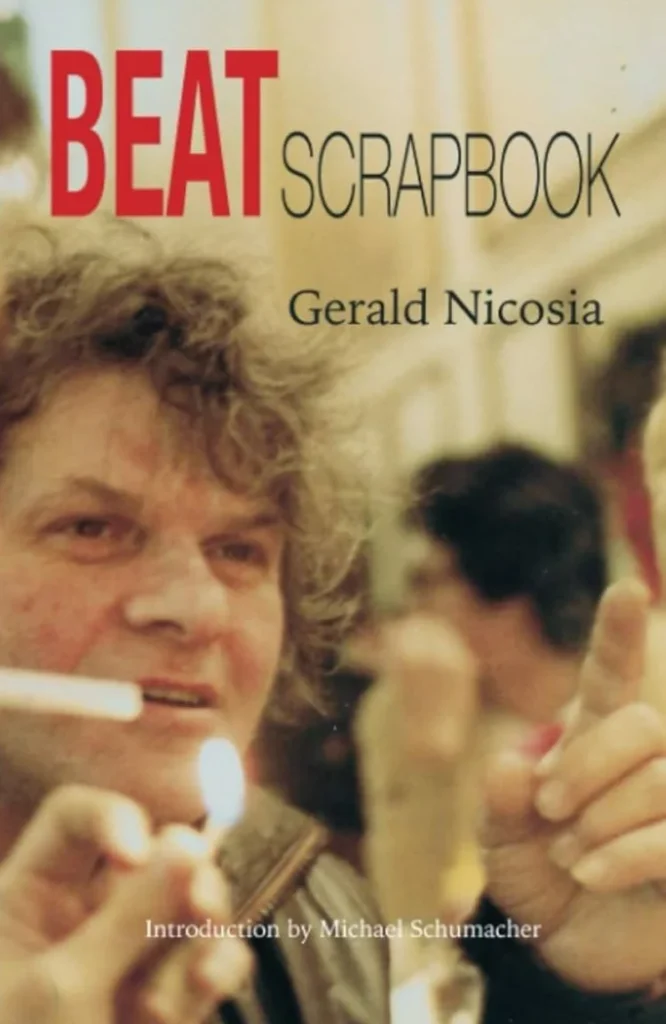

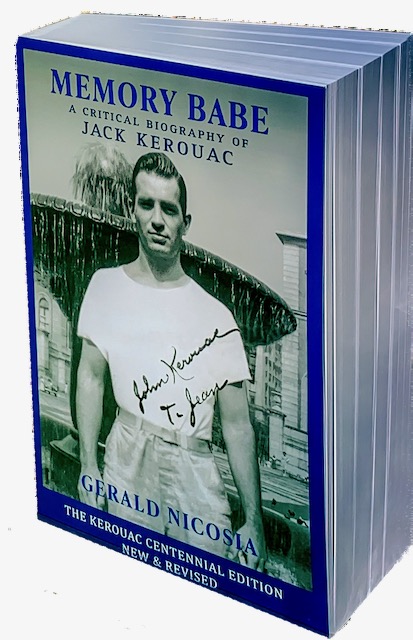

Two poets formed in San Francisco, Gerald Nicosia and Ron Myers, read poetry in the original San Francisco Beat, oral tradition. Nicosia, author of the seminal Kerouac bio, MEMORY BABE, was friends with many of the Beat writers including Gregory Corso and Jack Micheline, and he will read from his recent book of poetry BEAT SCRAPBOOK, which contains narrative-poem memoirs of dozens of the famous and non-famous Beat poets he knew during his many decades in the Bay Area.

Ron Myers, studied under Beat poet Harold Norse in the 1980’s and more recently post-Beat poet Neeli Cherkovski. Myers will read from his recently-published first book of poems, POWER SPOTS, with poems arising from many different San Francisco settings and characters he has known. Both poets deal with the core Beat themes: the importance of interpersonal relationships, tolerance toward people of different backgrounds and orientations, concerns with ecology and ending violent political conflicts, poetry that embodies an activist stance toward life, and poetry that is accessible to all people. The poets will allow time for a discussion with the audience after their reading.

It’s back! Tahoe’s Lit Fest Fall 2025.

Tahoe Literary Festival

Tahoe Literary Festival returned Oct. 10 and 11 in Tahoe City, CA.

The Tahoe Literary Festival celebrates the regions rich and diverse literary community and will feature a variety of free and ticketed events.

Whether you are an established writer, aspiring writer, avid reader, poet or passionate about the literary arts, The Tahoe Literary Festival is set to inspire, educate and illuminate Tahoe’s rich culture and creativity. The theme of this last year’s Festival is the Spirit of Place. The festival was created by Tahoe Guide Publisher Katherine E. Hill and Food Editor and writer Priya Hutner.

Sign up to the Tahoe Literary Festival newsletter to receive updates on the festival at bit.ly/tahoe_lit_fest.

Truckee Literary Crawl April 5th was a big success, featuring 48 creatives including MillValleyLit’s J.Macon King.

Readings at downtown Truckee, CA locations were held with poetry, fiction, storytelling, children’s authors, non-fiction and more from 48 creatives. All events were free.

See J.Macon King poetry and novel here.

J.Macon King acknowledges a poem encore from a full house at Truckee Literary Crawl. Alibi Pub. 3-5-2025. Photo: P.K.

Get LIT and keep us fired up. NEW Free original-design spiral notebook for a donation of $50.00 or more. While supplies last. Donate via VenmoVenmo profile(perry-king-5) or PayPal Info on donating and free notebook here.

From previous issues:

From Winter 2022 Issue 20:

Review of The Beatles: Get Back from Peter Jackson

“Get Back” to Basics

by

Just what the world needs: more Boomer Beatles reflections and recollections, right? Well, we have Peter Jackson to thank, or blame, for that. His masterful slice n’ dice of the miles of Beatles footage from the Let it Be and Abbey Road sessions transported aging Beatlemaniacs from around the world into the Wayback machine (or should that be the Getback machine?) for six glorious hours of sadness, silliness and timeless music.

I was just shy of ten years old, stretched out on the family room floor in my jammies, chin in my palms and eyeing the black and white Zenith, when Ed Sullivan so casually introduced the Fab Four on February 9th, 1964. Of course, we couldn’t much hear “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” or “I Saw Her Standing There” above the screaming teens, but the music was only part of the whole gestalt. This quickly became obvious when we donned our Beatle wigs and Beatle boots and lip-synched the songs with brooms, mops and trash cans.

Like a lot of kids in those days, the Beatles were IT for me, so IT that I spent the next 20 years trying to be one. It was profound, all-consuming. Some psychotherapists might consider adding “February 9, 1964” to the collection of Jungian archetypes affecting their Boomer patients.

When we juxtapose Ron Howard’s 2016 Eight Days a Week doc with Get Back, several truths become self-evident: First, from the Hamburg days to their final stadium gig at Candlestick in 1966, the lads were more or less together all the time. Under Brian Epstein’s and George Martin’s gentle tutelage, they became an entertainment industry unto themselves. Epstein’s death, along with their departure from the road was ultimately the seed of their undoing as a rock n’ roll band. In Get Back, we see them valiantly trying to recapture that spirit.

Of course, much has been written about the chemistry between John and Paul, and, even though they weren’t doing much songwriting together by 1969, there are uncanny musical interchanges in Get Back that illustrate the sort of kinetic mind-reading that happens when the muse decides two heads are better than one. And while the Lennon/McCartney bond is clearly fraying, it’s George who signals that the end is near with his somewhat understated walk-out. Upon his return, it’s clear that George has a soundtrack in his head that doesn’t include John and Paul. Meanwhile, Ringo plays the no-nonsense pro, miffed, perhaps, by the growing discord in the group. Yet there he sits, on his drum throne, day after day.

It’s only when we compare their subsequent solo efforts–Paul’s “Bowl of Cherries” album (aka McCartney), George’s All Things Must Pass, and John’s Plastic Ono Band–that we hear how far apart they were becoming, musically. There’s Paul’s “Granny Music” (as John refers to it on the show), John’s primal screaming and George’s Hari Krishna thing, all of it bubbling under the surface for years.

In the end, I was struck by how hard they worked, and how difficult it must have been with all the new and different music rattling around their brains (not to mention little Heather McCartney wreaking havoc in the studio). Bittersweet, to be sure, but also a timeless testimony to the collaborative, real-time creative process. And that’s when the magic happens.

End

Available to stream from Disney+.Images from Disney+.

See Jeb’s books at amazon.com/author/jebharrison

From previous Fall 2021 Issue #19:

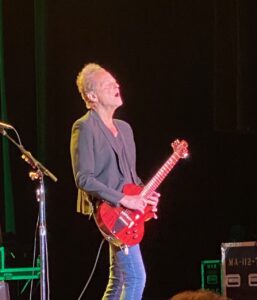

Lindsey Stirling wows Reno!

GSR Casino Sept. 4, 2021

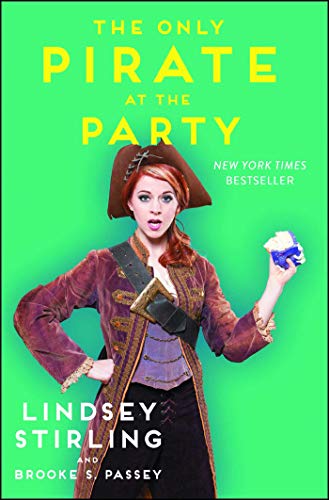

The Only Pirate at the Party

Dancing electronic violinist Lindsey Stirling shares her unconventional journey in an inspiring New York Times bestselling memoir filled with the energy, persistence, and humor that have helped her successfully pursue a passion outside the box.

A classically trained musician gone rogue, Lindsey Stirling is the epitome of independent, millennial-defined success: after being voted off the set of America’s Got Talent, she went on to amass more than ten million social media fans, record two full-length albums, release multiple hits with billions of YouTube views, and to tour sold-out venues across the world.

Lindsey is not afraid to be herself. In fact, it’s her confidence and individuality that have propelled her into the spotlight. But the road hasn’t been easy. After being rejected by talent scouts, music reps, and eventually on national television, Lindsey forged her own path, step by step. Detailing every trial and triumph she has experienced until now, Lindsey shares stories of her humble yet charmed childhood, humorous adolescence, life as a struggling musician, personal struggles with anorexia, and finally, success as a world-class entertainer. Lindsey’s magnetizing story—at once remarkable and universal—is a testimony that there is no singular recipe for success, and despite what people may say, sometimes it’s okay to be The Only Pirate at the Party. (Promo review.)

From previous Summer 2021 Issue #18:

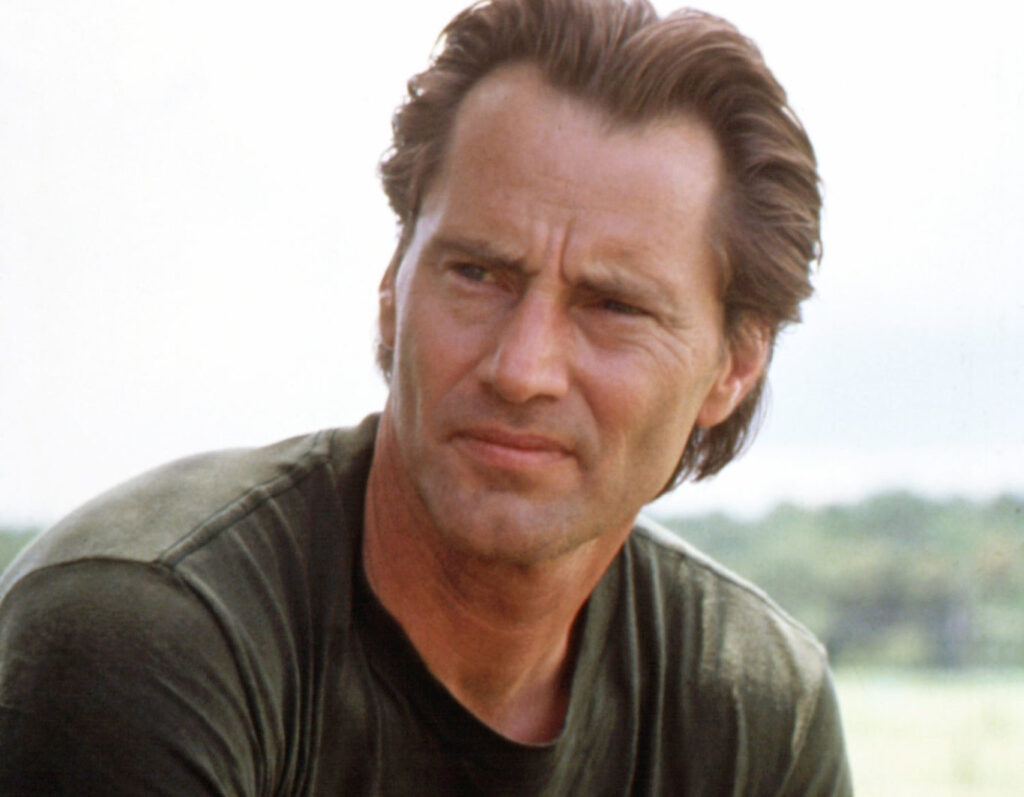

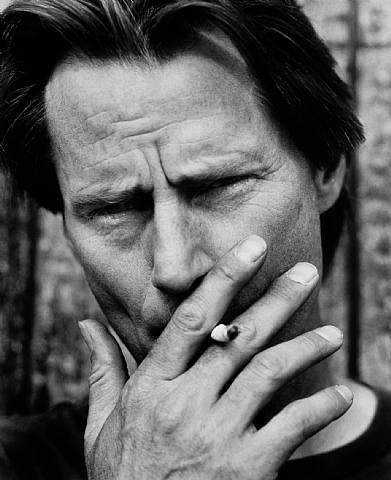

“…at thirty-five, admired by academics as well as rock fans, Sam Shepard would seem to be fortune’s child.”

Theatre scholar, Ruby Cohen.

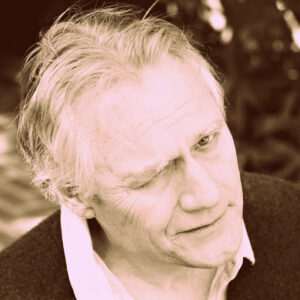

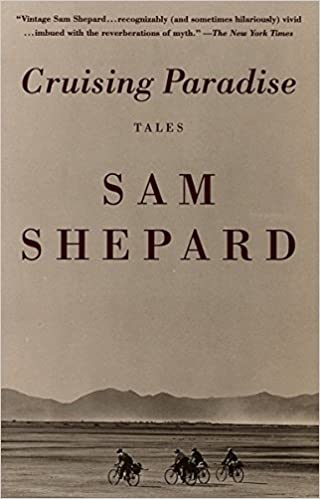

Cruising Paradise with Sam Shepard

By Michael Corrigan

Unrevised version originally published in Atticus Online, May 12, 2015. Note from Michael Corrigan: We lost Sam Shepard on 07/27/2017. He was 73. We will not have another classic Sam Shepard play, but it is hard to imagine a future world theatre without Buried Child in the repertoire of plays produced.

In 1979, Sam Shepard received the Pulitzer Prize for his dark drama, Buried Child, and in 1984, he earned an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff. In 1980, one of Shepard’s most popular “dysfunctional family” plays, True West, opened to acclaim; after three decades, it is often revived. A Lie of the Mind opened in 1985 and won the Drama Desk award that year for best play. In a recent interview, Shepard insisted A Lie of the Mind is a better play than Buried Child. Lie has not one but two dysfunctional families on stage, and possibly because of the split focus and length, A Lie of the Mind is rarely performed.

I worked with Sam Shepard at a 1980 playwrights’ festival in Marin, California. Playwrights invited to participate were selected out of the large number who applied. Originally, I was reluctant to attend. I had found some of Shepard’s early plays and their obligatory monologues to be pretentious, but Tooth of Crime resembled classical tragedy beginning close to its climax. I understood those rock and roll gods, Hoss and Crow, battling to the death. I loved the music, and it had biting, resonant lines: “You’re dancing a pantomime in the eye of a hurricane.” Beckett scholar, Ruby Cohn, saw the play as an exploration of American culture: “Through highly imaged rhythmic monologues and through dueling dialogues, Hoss and Crow reveal themselves intimately, and through them we gain insight into a contemporary cacophony of big business, crime, sports, astrology, art” (Cohn, “The Word is My Shepard,” 183).

The Marin festival grounds were well manicured and a theatre stood nearby. Director Robert Woodruff welcomed us and said the purpose of the workshop was to bring together creative talents and have an exciting festival of staged play readings and full productions. When Sam Shepard appeared, a cinematic image of the moody but doomed farmer from Days of Heaven came to mind. He seemed confident and shy sitting on the grass smoking an Old Gold cigarette, a bit reserved but polite.

“We don’t have to do anything,” he said, “but I have some exercises so that we can create and maybe find something new.”

A few murmured that he looked more like a rock star than a playwright. The Marin playwrights’ workshop included a few pampered wealthy artists playing at being playwrights. No one seemed to have a “real” job. The most successful playwright on the list, Henry David Hwang, never arrived.

Though considered a poet of the theatre, Shepard was wary of anything that sounded like “literature,” and seemed more comfortable discussing the care and racing of horses than theatre or Hollywood. Shepard is an accomplished equestrian, as the opening scene in The Right Stuff suggests. He felt Shakespeare “was a saint” but didn’t understand Chekhov. He admires Beckett and worked with actor, writer, Joseph Chaikin.

One of his main exercises encouraged a present tense, first-person monologue from the viewpoint of a single sense: sight, hearing, touch, taste or smell. The purpose of the exercise was to discover the “voice,” that inner murmur of language that lives in every character. The exercise seemed simple but daunting. It was hard to stay focused on one sense. When one writer said he was afraid to step away from what was comfortable, Shepard said, “That’s great. Fear can give you courage.” Writers read their monologues one by one. Shepard listened, and encouraged others to speak. He was non-judgmental, but one could tell which monologues intrigued him, including one of mine capturing the viewpoint of a blind man sitting in a car. Then we instructed to write another monologue combining the senses.

The next exercise was to create a sense of place and we were allowed two, then four lines of contrasting dialogue. The following is an example:

“Look at those wonderful redwoods. It’s a cathedral.”

“Yeah, it sure is. A lot of board feet.”

Sam Shepard brought in actors and musicians to work with the playwrights to create an authentic voice. Some of the actors later went on to considerable local or national fame: John Vickery on Broadway, Carl Lumbly on television, and Charles “Jimmy” Dean at the Berkeley Repertory Company and then the Aurora theatre. At times, the effect of voices, music and sounds made by an artist with many noise makers, created a striking effect. I was paired with Carl Lumbly, perhaps best known for his work on the series, Alias. A wonderful partner, Carl did a non-verbal improvisation of a mad person picking off imaginary bugs, and I wrote a monologue to match the improvisation. Carl did his improvisation without words, and then read the monologue. Evidently, my “mad” voice fit his remarkable creation.

For another piece, Charles Dean read a writer’s monologue about a ghostly ex-wife’s visitation, then did it in gibberish, and then did it while a Foley sound artist and a musician played along. Despite the pleasant lawn and Marin sunshine, something eerie and magical happened. The long gone ex-wife appeared.

This concept of “voice” perhaps explains Shepard’s skill as a playwright, since he gets inside his characters and finds their unique voices. Perhaps this is his shaman’s magic to bring rootless characters to life on stage. His strength lies not so much with his plots but with his imagery and his ability to create characters around images. He’s an “organic playwright,” and put a live sheep onstage for Curse of the Starving Class. Tilden scatters shucked corn leaves early in Buried Child. When Charles Dean played the condemned man in Killer’s Head, a short play consisting of a final monologue delivered before a convict is electrocuted, Shepard took him for a horseback ride and while overlooking a beautiful landscape, asked Dean to recite his monologue. Nature would inform the actor’s eventual performance.

The paparazzi invaded the grounds on the last day of the festival, driven by a “buzz” that an upcoming film, Resurrection, would make Shepard a film star despite his crooked teeth. They treated him more like a celebrity than a playwright who had received a Pulitzer. It gave the festival a validation to have so many photographers and writers surround us, but it also felt like an invasion. After making Frances with Jessica Lange and their subsequent love affair, Sam Shepard became a very real and very reluctant celebrity. In the words of Ruby Cohen: “at thirty-five, admired by academics as well as rock fans, Sam Shepard would seem to be fortune’s child” (Cohn, 171). As one of Shepard’s characters states, he was “riding in a state of grace.” His appearance in Bob Dylan’s improvised uneven film, Renaldo and Clara, led to Shepard’s casting in Malick’s remarkable film, Days of Heaven.

It is a sad fact but even the most acclaimed playwrights, if they live long enough, will see their plays go out of fashion. George Bernard Shaw was the exception. John Osborne and Tennessee Williams saw this happen, and Sam Shepard has seen his acclaim fade. Tastes change, and the new work seems less effective, the past work somehow dated. Though his career as a film actor has flourished, despite turning down some lead roles and deliberately avoiding exposure, Sam Shepard has not repeated the artistic success of his most celebrated play, Buried Child, often compared to Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming. Both plays have shocking endings, Pinter’s subdued, Shepard’s verging on horror.

I saw the premiere of Buried Child which featured Joe Gistirak as Dodge, a bitter old man who drinks throughout the play. I had directed Joe Gistirak in Krapps’s Last Tape; he was memorable as Beckett’s isolated banana–eating 69-year-old Krapp and extremely effective as the caustic Dodge. Sadly, Joe took his life shortly after the play closed. Buried Child then opened in New York taking the Pulitzer. In the final scene, Tilden, mentally challenged, enters carrying a dug-up corpse of an infant killed by Dodge and possibly a product of incest; he takes the body upstairs to the mother as she describes the sudden garden flourishing outside. It is one of the most harrowing scenes in American theatre.

After A Fool for Love and A Lie of the Mind, the subsequent plays seemed less effective. States of Shock received a mixed critical response. Ages of the Moon was considered an echo of Shepard’s earlier success, and his most recent play, Heartless, opened to tepid reviews in the summer of 2012. After referring to Shepard’s greater works, Buried Child, Curse of the Starving Class and True West, the New York Times critic, Ben Brantley, wrote the following: “Heartless, which opens on Monday night at the Pershing Square Signature Center, provides only flashes of the glorious theatrical glee and anguish that animate those plays.” The critic continues suggesting that the production calls “ponderous attention to its great metaphysical themes,” that Heartless is unique in the sense that it has a large female cast, and Lois Smith has a powerful monologue at the end about seeing James Dean on the screen at a drive-in. (Ironically, Lois Smith herself performed opposite Dean in East of Eden.) For Brantley, Shepard’s “murky play” is somewhat “illuminated” by Lois Smith’s performance. If Heartless proved generally disappointing, Ethan Hawke revived A Lie of the Mind to great acclaim in 2010.

Some critics have dismissed Sam Shepard’s screenplays and subsequent original films, and in interviews, Shepard himself feels they are awkward. They certainly lack the power of the best mature plays, and Shepard has dismissed many of his earlier experimental plays as just that—early awkward experiments.

As Sam Shepard entered his seventies, he had to ask: where do I go from here? Could the late Ruby Cohn’s 1982 article, “The Word is My Shepard,” one day mark the end of Sam Shepard’s power as a playwright rather than a new beginning? F. Scott Fitzgerald famously stated that “there are no second acts in American lives.” Ironically, Ruby Cohn compares Shepard to Fitzgerald in that early article: “Like the Fitzgerald of The Great Gatsby, Shepard is at once seduced by and critical of American wealth and its artifacts” (Cohn, 186).

Though we have not seen a major Sam Shepard play since the late 1980s, a reminder of his origins as an American writer can be found in Cruising Paradise, a collection of stories, tales and anecdotes published in 1995. This book of prose is more personal than the others. Shepard’s earliest memory starts in Mountain Home, Idaho, where his father, a bomber pilot, was briefly stationed during World War II. The chapter, Days of Blackouts, begins with old news bites:

“1943:

…Eisenhower is made Supreme Commander of all Allied forces.

Mussolini resigns.

My dad is dropping bombs on Italy.

I’m born

Without a clue” (Sam Shepard, Cruising Paradise, 17).

The headlines are part of history, but there is something remarkable about a writer describing a childhood scene he could not possibly remember. The Mountain Home experience suggests a war time suspense thriller as Shepard’s father (Sam Rogers) uses a “secret code system” with the mother so she can find the exact room number and meet him. (The war does not allow pilots to reveal their location.) Shepard describes the vanished motor court “laid out in the shape of a horseshoe, with all the identical bungalow units surrounding a shallow concrete fish pond, glowing a pale green from a footlight submerged in the middle of it.” The setting is bleak and austere with “two metal lawn chairs facing the pond, underneath a pair of white pines” (Shepard, 17).

The title, Days of Blackouts, has a meaning beyond bombing raids; Shepard’s father, an alcoholic, ended badly. What happened that night in 1943 seems to provide Shepard with a strong life metaphor:

“The family sits around the pond. As the father holds the infant, the mother points out a fish to the baby, losing a flower in the process. My father makes a lunge for it and loses me. Now I’m airborne, flying towards the shiny pond and the falling hibiscus. I’m suspended, watching the flower touch down softly on the surface without sinking, and twirling like a ballerina, just before I crash into the rippling green light. My blanket is floating beside me” (Shepard, 19).

Shepard conjures up what happens later that night when his infant sleep is disturbed by the father “having a nightmare on one of the twin beds in the bungalow of the motor court in Mountain Home, Idaho.” The child has been placed “in the bottom drawer of the dresser that’s been pulled out on a throw rug.” His blanket is drying by the windows. He can “hear it dripping.”

Ultimately, it is the sad image of Shepard’s father that haunts these pages even as his derelict image haunts Shepard’s plays. In a chapter called See You in My Dreams, Shepard recounts the death of his father:

“They were easy to remember: a very fat Apache woman with bare feet, and a tall, stringy white man with a red beard and a crew cut, both raging drunk. They careened their way from one end of town to the other, getting ousted from every bar until the money ran out…my dad staggered into the middle of the road and met his death” (Shepard, 142).

Even after death, the father presents a frightening image to the son as he stops in front of his father’s one room apartment “afraid to go in” because of “the same fear” that invaded the playwright when his father was alive—“the very same fear” (Shepard, 145).

Buried Child features a dysfunctional bizarre family: the mentally challenged Tilden shucking corn from a garden that shouldn’t exist, a sadistic brother who has accidentally cut of his leg with a chain saw, a mother who often delivers monologues off stage, and Dodge, a kind of cynical chorus and old derelict waiting to die. Shepard’s father saw the play, but did he recognize himself before being evicted for disrupting the performance? At the funeral, Shepard reads from his father’s favorite poet, Lorca, and finds himself, a private man, breaking with very public grief. There is nothing left but a pine box full of ashes.

“The gravediggers turned their backs toward me and lowered their heads. I was grateful to them for that” (Shepard, 150).

With the 1983 death of his father, Sam Shepard may have lost a source of inspiration: the alcoholic father destined to abandon the family and wander the desert. A 2009 arrest for drunk driving indicates Shepard may have inherited his father’s addiction. The disturbing mug shot of Sam Shepard suggests some rough road the playwright has traveled since his striking film debut in Terrance Malick’s Days of Heaven. After his arrest, Shepard quit drinking, but his partnership with Jessica Lange ended quietly in 2010. In May of 2015, Shepard was arrested again for aggravated drunk driving.

At the Marin festival, Sam Shepard led a group of playwrights searching for the hidden “voice” that drives every dramatic character. If Sam Shepard is a writer who loves and fears America’s vastness, he has listened to its voices. It is an American vision, one that may have started that night in Mountain Home, Idaho, when a father dropped his infant son into a shiny motel pond. Though Sam Shepard states at one point that he was “born without a clue,” Cruising Paradise provides a few biographical insights into this enigmatic artist.

In the fall of 2012, Trinity College in Dublin awarded Sam Shepard an honorary doctorate. He read from his work and performed a few songs with Patti Smith with whom he wrote an early play, Cowboy Mouth. Smith recently won a Pulitzer for her poignant memoir, Just Kids. Shepard insisted he will never write a memoir but continued to work as an actor, usually in supporting roles. He appeared in the acclaimed film, Mud. As a writer, certainly Sam Shepard had more to say. In an interview with Carole Cadwalladr, Shepard said that regarding success, “Behind it is a certain horrible emptiness…it’s the writing itself which is important.” Sadly, this unique American voice can never give us another classic play, but there will certainly be revivals for years to come.

END

* * *

References:

Brantley, Ben, New York Times, 2012

Cohn, Ruby, “The Word is my Shepard,” 1983

Shepard, Sam. Cruising Paradise, 1995

Shepard, Sam, The Tooth of Crime, 1972

The author’s journal kept during Sam Shepard’s playwrights’ workshop is available as an eBook: Sam Shepard’s Playwrights’ Workshop: 1980: a Journey of Exploration at https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0768KVWMR

About Michael Corrigan

I was born in San Francisco and received an MA in creative writing from San Francisco State. I’ve been actively involved in theatre, and worked with several theatre and film artists, including Sam Shepard and Peter Coyote. I attended the American Film Institute to study screenwriting. I’ve worked as a teacher of speech communications and English. I have published 13 books, including Mulligan and a road novel, Down the Highway. They are also available through Kindle. I have written extensively about the Irish American experience, and received a Pushcart Prize nomination for the story, “Free Fall.” I am also a folk-blues enthusiast and play acoustic guitar. The arts publication, The Scream Online, published stories from my book, These Precious Hours, in serial form. Alex Hyde-White narrates the audiobook of These Precious Hours and Mulligan, a novel about, in part, the Irish in the Civil War. Confessions of a Shanty Irishman, The Filmmakers and A Year and a Day are also available as audiobooks. A play, Letters from Rebecca, was broadcast on NPR and is an audiobook. My most recent novel is Brewer’s Odyssey, about a reluctant psychic facing a dark future.

*https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2017/dec/17/sam-shepard-remembered-by-johnny-dark-obituary-2017

From previous Summer 2021 Issue #18:

HEM review by Jeb Harrison

Hemingway, the 2021 three-part, six-hour documentary film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. Narrated by former MillValleyite, Peter Coyote.

As a writer, I have tried to avoid digging too deep into the lives of my literary heroes, for obvious reasons. There are few angels there, and, in the case of Hemingway and many of his contemporaries, more devils than any fan would care to hear about.

In the new Ken Burns/Lynn Novick documentary, little new information is revealed about the life of “Papa,” his four wives or his children. Like many biopics on Hemingway, it’s easy to walk away from the Burns/Novick documentary with the prevailing sentiment that he was a great writer and a terrible person, particularly when viewed through the cultural lens of 2021. The same could be said of Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, and many other white male writers from the first half of the twentieth century.

Despite the current tendency to judge the behavior public figures of the past without regard to the belief systems and social context of the times in which they lived, Burns/Novick make some interesting observations about Hemingway, going as far to suggest that his hyper masculine persona was a cover up, or avatar as they put it, to compensate for an androgynous childhood. (Having a trans son in Gregory couldn’t have helped.) While the idea that this supposed psychological conflict pushed Hemingway to pursue extremely dangerous recreations is a plausible theory, I’m not sure it fully explains what appears to many as a “death wish,” pure and simple.

Aside from the moving profile of Hemingway’s tortured soul, and all the salves he applied to soothe it, I came away with two conclusions:

First, “once an adrenaline junky, always an adrenaline junky.” After all the concussions and other injuries, when he realized he could no longer get high off hunting, fishing, sex and ultimately booze, and the critics laid into him like sharks into a hard-fought marlin. He followed in his father’s footsteps and surrendered.

Second: Hemingway wasn’t the first to create a public persona, or avatar, the didn’t necessarily jibe with his writerly sensibilities. But he certainly helped paved the way for celebrities of all stripes to “act a part” that made them appear to be something they were not.

I’m saddened that many of today’s readers allow the lifestyle of the artist to cloud the appreciation of the work. Yet when we witness the flashes of brilliance and the impact of Hemingway’s writing on the literary canon, whether we like the work or not, we can’t deny that genius and madness often go hand in hand. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick make that unfortunate fact abundantly clear.

From PBS TV and available free through streaming channels.

End

Jeb Stewart Harrison is the author of three novels: Hack, 2012. The Healing of Howard Brown, winner of the 2017 Independent Press Award for Literary Fiction and the 2020 Firebird Award. American Corporate, 2019 Independent Press Distinguished Favorite. His short story collection is previewed here.

The following are from previous issues:

Hemingway in Mill Valley?

A “…Mill Valley house with Mount Tamalpais views that was owned in the 1960s by John “Jack” Hemingway, novelist Ernest Hemingway’s eldest son, and his wife Byra…” Paul Liberatore reported in the Marin Independent Journal in 2012 when the house went on the market for “for somewhere between $2 million and $3 million.”

Jack, called “Bumby” in his childhood, was the first-born of three sons of Hemingway. Jack’s godmother was Gertrude Stein. Jack and his wife’s “…daughter, actress and writer Mariel Hemingway, was born in Mill Valley in 1961, the year her famed grandfather ended his life in his Ketchum, Idaho, home with a blast from a silver-inlaid, double-barreled shotgun. For the first six years of her life, Mariel lived in the 400 Vista Linda house with her two older sisters, Joan, aka “Muffet,” and Margaux, a troubled actress and model who died of a drug overdose in 1996 when she was 42.”

It is unclear if Papa himself had visited Mill Valley. See review of Ken Burn’s “Hemingway” in The Scene.

From MillValleyLit Fall 2020 Issue #17:

ruth weiss (1928 – 2020), pioneering female beat poet, died: Friday, July 31 at the age of 92 at her cabin near Mendocino, California. (Note lower case spelling of her name was her artistic preference.) Some say the German-born spitfire introduced jazz poetry to San Francisco and even influenced Jack Kerouac, with whom she became close. She was cited in “Breaking the Rule of Cool: Interviewing and Reading Women Beat Writers.” Her most recognized work, “Desert Journal,” was released in 1977. A 2019 documentary about her life was released titled, “Ruth Weiss, the Beat Goddess.”

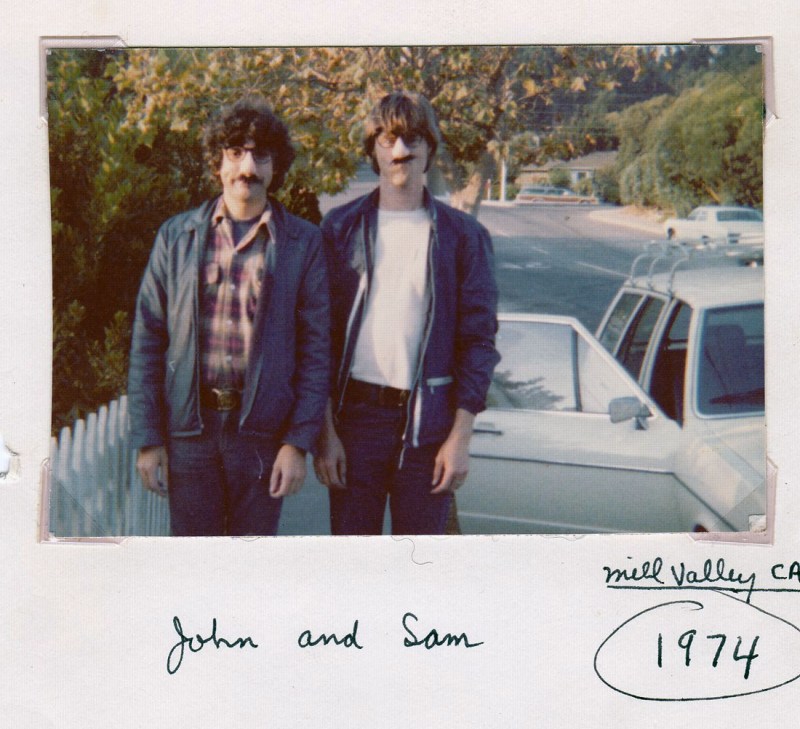

Exclusive photos from Beat expert, poet, writer Gerald Nicosia—

In June 2011, Gerald Nicosia threw an 83rd birthday party for ruth at the Art House Gallery in Oakland. Gerald reports, “We had a mob there that night. I had a giant birthday cake for ruth with 83 candles on it.”

For previous and archived The Scene articles click here: