From previous issue #21:

An Angel Without Wings

by E.S. “Scotty” DeWolf based on a true San Francisco story

Part 1

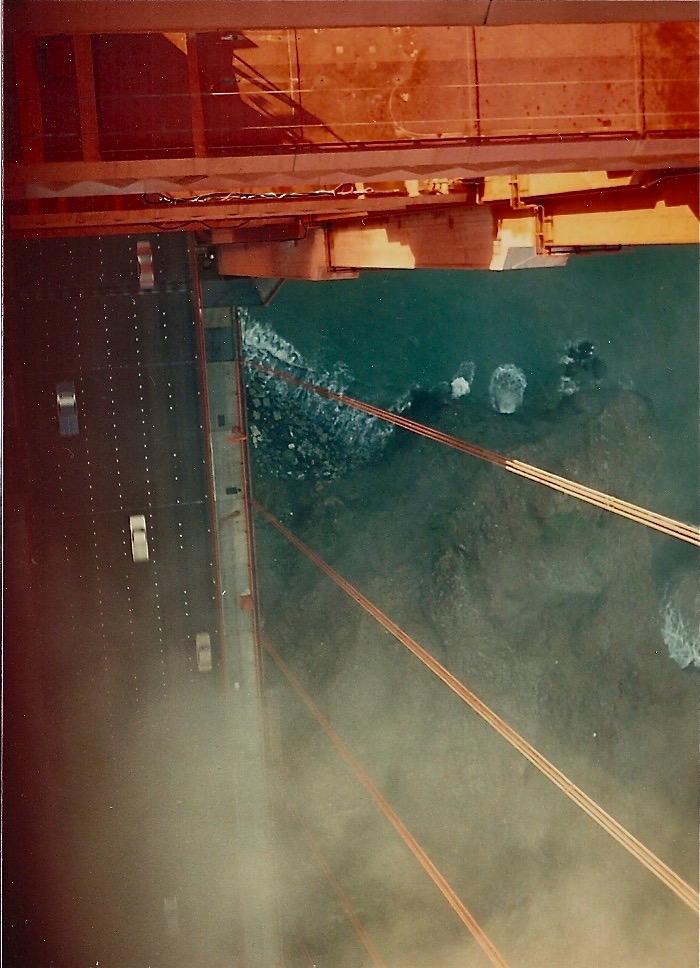

Edward decided he would wait till there was a bank of fog coming in from the ocean, that often creeped up to the level of the bridge safety railings along the walkway. He figured it would be a lot easier to slip off the side of the rail into the fog when he could not see the churning waters below.

Edward had done some research at the San Francisco library and found medical research on falling from that height—that the blood would leave his head and that he would lose consciousness before he hit the water. That was encouraging because he figured he would not feel a thing. It would “be like striking a concrete surface, assuring that death would be swift and certain.” Edward did not realize that this information had proved wrong for a number of mangled wide-awake jumpers from the Golden Gate Bridge.

That night Edward composed several notes to tape on the bridge, until he came up with the one he was satisfied with. He tore up the others, took the note and the tape with him, and not much of anything else…

Two weeks earlier

San Francisco’s famed Palace Hotel features a majestic stained-glass dome covering the entire Garden Court dining room, with Austrian crystal chandeliers dangling like enormous earrings. Edward could not stop himself, amongst the tables of finely dressed diners, to gaze upward at the Victorian splendor. He found himself wondering if his mother had fancy earrings.

Edward had been away from home for the better part of two years and was now barely nineteen years old, living on the streets in San Francisco and sometimes across the Bay in Berkeley. The warm Indian Summer of autumn had set in, and Edward had just been hired part- time at “The Palace,” as those familiar called it, as bus boy and dishwasher. His life was finally looking up.

Perhaps his mother had eaten here. Perhaps even with his father. Wouldn’t that be something? He had no clue, since he had no idea who his real parents were. They could be here right now. He jerked his head around.

Bang, crash, clatter! Nearby diners stared at Edward. His boss glared at Edward. Edward had done it again. Red-faced, Edward the bus boy, quickly trundled his cart with broken dishes toward the kitchen.

Edward would soon discover the dreadfully broken truth about his parents. Edward had a very bad stuttering and stammering condition since he started talking, late at three-and-a-half years old. This made it difficult for him to get any kind of job where communicating with the public was required, and he felt lucky to get this one. He had only had this job for a week, and now aspired of getting a weekly room at the YMCA in Berkeley or San Francisco as soon as he could save up the money. A friend in Berkeley, with a modest apartment, let Edward stay there for a night or two at a time so he could shower, clean up, and wash his clothes for this job.

Not very graceful, to say the least, Edward seemed to have a hard time busing the dishes quietly as he was instructed to do. Several times he had dropped a bus tray brimming with glassware, breaking quite a few dishes.

When Edward picked up his first weekly pay envelope from the Palace Hotel he was very excited. He opened it, and quickly realized that after paying back his friend and his job for food he’d eaten, and buying a few items of used clothing at the Salvation Army thrift shop, he’d have only a few dollars left.

Edward was off work on Saturday and planned to head back to San Francisco to hear a free pipe organ concert at the Palace of the Legion of Honor in Golden Gate Park. Edward had taught himself to play keyboards at less than five-years-old, and shocked his foster parents and the priest when he asked to sit at the enormous church organ and improvised a tune in a perfect pitch.

He had calculated his funds: bus fare from the East Bay, plus the inexpensive San Francisco Muni system, which with a transfer ticket you could go anywhere in the city. And he could afford to get a hot dog or two at the Fun Center on Market Street. The Fun Center was an old-fashioned arcade with Skee-Ball and pinball, and Edward’s favorite hot dog stand right in front. He licked his lips, anticipating the hot dogs because they were cheap and of a good quality, and perfectly slathered with sweet hot dog mustard and relish. First, he visited Chinatown, which felt to Edward as if he were dropped smack into another land. Chinatown produce was super reasonable and he picked up a bag of fresh fruit, and then walked quickly through Union Square to the stand.

“Here it is!…Here it is!”

The vendor had a thick New York accent and would thrust out a hot dog and repeat his mantra, which never changed. The stand was next to the sidewalk so the man selling the hot dogs could pitch directly to the passersby, who were compelled to look to see what the excitement of “it” was.

Just as Edward was about to order, he noticed an old man in a long gray overcoat digging around in the public garbage can right in front of the hotdog stand.

“Hey! Mister. Don’t eat that stuff!” Edward yelled. Edward walked over to the old man, whose head popped up from garbage can. His long gray hair and long beard fluttered in the strong Market Street wind.

“Hey Mister…you could get sick from that stuff. Here…take this bag of fruit for now. I am going to get us both a hot dog.”

The man, in his late sixties or early seventies, smiled and asked Edward, “Are you sure you can afford to do that, son?”

“Sure,” Edward assured him. He added with pride, “I will still have enough to get me breakfast tomorrow before I have to go to work at my new job as a bus boy.”

Edward could tell the man was not a drunk, but just an old guy who was obviously hungry. Living mostly on the streets at that time, Edward had a sincere sympathy for a lot of the old folks who had a hard time getting along and finding enough food to eat. He often would share what he had to eat with such people, especially if they seemed truly destitute.

The old man noticed that Edward spoke very haltingly and stuttered uncontrollably, often stopping on certain consonants he could not get out for the longest time, while his eye-lids fluttered faster as he struggled to get a word out.

Edward noticed that the old man had very caring and kind looking eyes, and seemed very pleased that Edward would spend his money to get him a hot dog. Edward ordered two hot dogs with mustard and relish and one bag of potato chips. Inside of a minute the vendor handed over the food all wrapped up in wax paper, with the chips. Edward planned to sit with the old man at a bus stop bench so they could share the food. When he turned around, the old man was gone.

Market, the central downtown street, was always heavy with pedestrian traffic, and Edward looked both directions to see where he might have gone. He was prepared to chase him down and give him his hot dog. But he was nowhere in sight. Edward turned back to the hot dog man and asked him if he noticed which way the old man went, the one digging in the garbage.

“Whaddaya talkin’ about, pal?” the vendor responded in his New York tone. He stared at Edward. “I didn’t see nobody dere. You was talking’ to yourself.”

Edward was genuinely sad he was not able to find this old guy to give him his hot dog, as he was certain the old guy was pretty hungry to be looking for something to eat in that dirty old garbage can. And he was genuinely mystified. He felt a bit lonely now, and wished he could have shared with the old guy who seemed to have disappeared into thin air. Edward sat at the Muni bus stop bench and ate both hot dogs and the whole bag of chips.

When Edward went back to his job on Monday, the supervisor suddenly loomed before him. He told Edward that he HAD to take extra care not to make much noise when clearing the tables and stacking the dishes in the bus cart. “Kid, you broke several plates and cups and at least three glasses your first week on the job.”

Edward knew he was clumsy that way, but resolved he would try really hard to do things the way they wanted. But try as he did, he was still having dishes and glasses slip from his hands, and making racket even though he was trying to quietly put them in the large cart. And, as hard as he tried, he actually broke a few more dishes than the previous week.

At the end of the week, when he picked up his pay envelope, his supervisor called Edward aside. He politely but firmly told Edward that that this was to be his last pay envelope. The waiter captain said he simply could not have that much noise when the dirty dishes were gathered, and that the hotel could not afford to keep him because of the cost of dishes he was regularly breaking.

Out of the beautiful Palace, and back on bustling Market Street, a sick, sinking feeling welled up in Edward’s stomach. The reality set in: that the job he was counting on to take him off the streets was now gone and he was hardcore homeless again. He could no longer get a weekly room at the YMCA. He felt depressed at the thought of having to continue the homeless lifestyle, and not seeing much chance of that situation changing anytime soon. After his small funds ran out he knew he would be chowing down yet again at St. Anthony’s dining room on Golden Gate Avenue, run by the Franciscan fathers at St. Boniface Church. There he could get at least one meal a day and would have to scrounge and hustle some spare change to be able to survive. The chill and rain and damp of winter was coming and living on the streets would soon be particularly harsh and unpleasant.

There were several mortuaries in the city that had hired him before to play for funerals.

These events gave Edward conflicted moods. His organ playing, the one thing he could do really well, lifted him and filled him with confidence, as it did when he taught himself piano at an early age. He also could become low-spirited, with all the grieving and tears and all, but he felt that the music was important for the effect on the departed’s loved ones. He played Safe in the Arms of Jesus and God Be With You Till We Meet Again as if it was one of his unknown family members lying cold in the casket. His mother, brother, grandfather… as it may have been. Edward hoped that when he passed, someone like himself would play the organ. Edward filled with self-pity, wondering if anyone would come to his funeral, and if, with no money, could he even have one?

The pay was meager for playing fifteen minutes before each service, but every little bit helped. Since he was not very well dressed and unable to bathe regularly, these jobs became fewer, as most did not hire him again unless they were desperate.

#

Edward could not shake his deepening depression no matter what. He felt even worse when he thought back to his foster Mom mocking him when he threatened to leave home. Edward had left home twice before starting at age fifteen, but had always returned.

“The way you talk, and clumsy as you are, I don’t think you could even hold down a job washing dishes. You are stupid and can’t do much of anything except read your damn books.” “That’s all you’re good for. You have been a good for nothing stupid ass as long as we can remember.” “You are really a hopeless case who will have to have someone or some institution taking care of you, since you are totally incapable of taking care of yourself. If you do leave again,” she told him. “You will be back begging for a meal and a place to sleep, mark my words!”

He replied, in his halting stammering way, “I would rather starve and freeze to death rather than come back to this crazy house!”

Edward almost never had spoken up to her like that and she slapped him hard back and forth on the face several times, then clenched her fist and socked him hard in his shoulder where it would hurt for days. He remembered back to that night in June. How scary but liberating when his one friend from high school helped him escape out of the bedroom window. Edward carried only the clothes on his back and a paper bag with underwear, socks, peanuts and candy. He was seventeen with seventeen dollars in his pocket. This time, he knew he would never come back.

His mind jogged back into his present situation. He began thinking that the old lady was probably right after all…Maybe his situation was totally hopeless. With no future where he could hold down a steady job and be able to afford a roof over his head. He headed the Tenderloin district and managed to hang around with some older winos. He bummed chugs off their wine bottles till they wouldn’t let him have anymore Then he bought his own bottle of cheap wine and proceeded to get really drunk.

Edward rode the bus that night to his favorite part of Golden Gate Park, near the Palace of the Legion of Honor. Edward did not know what the word irony meant but he knew what it felt like: the fact that he went from The Palace to this Palace, but he was far from being a prince. Quite the opposite. His options were now bleak.

The Palace was where he attended many free organ concerts. He knew of some nice treed areas where he had previously spent a few nights and he rolled out his sleeping bag undisturbed. No one had ever bothered him there, except the occasional other bums who lived in the park nearby, whose occupation seemed to be bumming a cigarette. Maybe that’s why they called them bums, Edward thought. Edward made his own with a hand operated cigarette roller, called the “Bugler Thrift Kit,” at a fraction of the cost of buying regular packs. As Edward huddled there with his kit, his exhaled smoke swirled, mixing with the fog, now drifting in from the coast with a damp chill.

Nearby was the Golden Gate Bridge, and its fog horns began to blow. As San Franciscans know, the brassy horns can blow either poetically or desolately, depending on one’s mood. Edward decided to walk across the Golden Gate Bridge in the morning, to the quaint bayside town of Sausalito. He liked Sausalito, as Bohemian artists and writers hung out there in the cafes and bookstore, and who seemed more accepting of peculiar mannerisms. Of someone like Edward for instance. Edward heard a crinkle, and in a rip in his sleeping bag he found a few dollars he had hidden there one drunken night. Edward smiled and drifted to sleep with some optimism.

The next day, instead of going to Sausalito he started drinking with some bums in the Park, and then got drunk in the streets of San Francisco, and stayed drunk the whole weekend. The more he drank that weekend, the more depressed he became. Between the guilt of drinking and smoking up his money, the voice of his foster mother began echoing in his ear about his hopeless prospects for a normal life.

On the second evening of his binge drinking Edward’s thoughts became more serious: suicide was the only answer that made any sense to him. He could not consider a gun, as he did not have the money for a gun and bullets, and with his luck, he’d probably get busted by the cops. A doctor’s prescription was necessary for barbiturates to overdose himself, but again, no money .

After studying all the suicide options he could think of, Edward came to the conclusion that the only viable one for him would be a leap off of the Golden Gate Bridge. There was one problem: Edward was afraid of heights. and would get nauseous just leaning over the guard rail of the bridge.

Edward decided he would wait till there was a bank of fog coming in from the ocean, that often creeped up to the level of the bridge safety railings along the walkway. He figured it would be a lot easier to jump off the rail then when he could not see down to the churning waters below.

On the day Edward walked out on the bridge to kill himself, he ate his last meal at an American Chinese restaurant that, for one very cheap price, offered a complete dinner, including a cup of coffee and pudding for dessert. The 85 cents in change left, he decided to leave on the Bridge walkway, in hopes that someone who really needed it would find it and be happy of their discovery.

Into a half pint bottle of cheap vodka, he’d saved, he poured root beer for flavor. He drank it slowly on his walk to the bridge from a paper bag because one could be arrested for exposing the bottle. It was not enough to get him really drunk, but enough he felt, to give him courage.

He used the walkway on the east side so he could have one last look at the city of his birth before he made the final move over the rail. The bridge had a lot of pedestrians and bicyclists going fast in either direction and no one seemed to pay any attention to Edward. The fog had crept up to the level of the walkway by the time he got out to the middle of the bridge. He attached his little note to the bridge railing. He decided the easy and slow roll off the rail would be his best option rather than go feet first or head first. He looked over the side and could only see a thick blanket of fog. Thank God for that.

Edward said a last prayer to Jesus and his Mother Mary, asking them to tell God for him, that he really had no choice and hoped he would not have to stay in purgatory for very long. His foster parents raised him as a Catholic, though he never attended church service after he left home. He figured since God was supposed to know everything, that he would know that he had a good reason to end it all and hope to break into heaven at some point. He ended his last prayer for forgiveness and made the sign of the cross and straddled the round rail. He was now ready for the gentle roll over the side into the thick gray carpet of fog.

With his eyes closed Edward took a deep breath and started to slowly lean over the side. He felt a tap on his shoulder and a familiar kind voice speaking softly to him.

“Don’t do that, son…you are going to make this old man cry? You wouldn’t want to see a grown man cry now, would you?”

Edward instantly opened his eyes and saw the same old guy who was at the garbage can the week before he lost his job at the Palace. He put his hand on Edward’s left shoulder and coaxed him off the rail and back onto the walkway. His face was just a few inches from Edward’s, and Edward could look into his moist sad eyes that seemed so sincere and kind that it kind of shook him up, and he somehow felt sorry for this old guy, that he knew was destitute and down and out himself. He had a strong sense that this old man really was sad at the thought of Edward going off the bridge and dying.

Edward was convinced that there was no one on this earth that would have cared if he lived or died, but this kind old guy seemed to genuinely care. Edward was speechless for a few moments realizing that had the old man come even ten seconds later, that he already would have rolled over the side and on his way down to the angry waters and certain death. The man gently grabbed Edward’s hand and guided him away from the rail, and waved off several folks who had gathered to see what was going on. The old man turned to the group of three or four people who had stopped and told them that everything was all right, that the kid had just lost his balance while trying to look at the view. He told then to go on and not worry, which they did.

Edward looked at the old man and finally said, “Say, mister, I got two questions for you. Number one, why did you run away, right when I was going to give you a tasty hot dog that day you were so hungry digging in the garbage can in front of the Fun Center? I wasn’t turned around a minute when I went to hand you that hot dog, and you were gone, and I could not find you walking in either direction? Why didn’t you stay to get your hot dog from me?”

The old man looked into Edward’s eyes with a kind smile that made Edward feel like he really cared. It occurred to Edward that he would have loved to have had a parent who would look at him with love in their eyes like that.

The man patted Edward’s shoulder and said, “Son, I walked away from you as soon as you turned to buy that hot dog for me, because I figured you were kind of hungry yourself and could probably use both of those hot dogs to fill you up. Besides, it was so kind of you to give me the last of your fresh fruit. It filled me up nicely. I was so touched that you cared enough to give an old bum like me what food you had with you, and then willing to buy me a hot dog when your own funds were so low.”

“So, my other question, Mister, is how in the hell did you get out to the middle of this bridge? This is a long, long walk in a lot of wind, and you are a very old man that doesn’t seem to be able to walk very fast?” Edward noticed that this man, unlike others, seemed very patient and unconcerned that it took Edward a long time to get his words out. And Edward was so anxious to hear the answer to his second question that he could scarcely get them out.

“Son,” the old man said to Edward, “that is not what is important now. I can see that the way you talk has caused you a lot of problems, but I need to tell you that even though it may be hard for you to believe, you are going to meet someone and fairly soon that is going to be able to help you with that speech problem you have, and that is going to change your life more than you could ever know.”

Edward looked at him and figured he might be delusional or senile in his old age. But some part of him desperately wanted to believe it might be true. So rather than hurt the old man’s feelings, he asked him, as if to go along with the gag, “So when do you figure I am going to meet this person who can help me?”

The old man continued to look kindly into Edward’s inquiring eyes and told him, “Very soon, Son…very soon. You will remember me telling you this after you begin speaking very well, and your life keeps getting better, after meeting this man who can help you.”

Something about the way he said this and looked at Edward, nearly convinced him that it was a possibility. Edward picked up the change he had laid down on the sidewalk near the bridge rail, and offered to give the old man part of it. The man said he was going to be eating OK later that day and that he wanted Edward to keep that change for himself. Edward thanked him for saving him from what he was about to do, then offered to help him walk back to the city, and get them something to eat when they got back.

The man instructed Edward to turn around and take the suicide note off the rail and throw it over into the water below. And to say a prayer of thanksgiving to the Lord for saving him that day. After that he would go with Edward back to the city

Edward turned toward the guard rail and took the note off, rolled it up into a ball and before tossing it into the bay below, he did offer a very fast prayer of thanksgiving that was one sentence. His prayer was, “Thanks dear Lord for sending this man to talk me out of this and I pray that he is right that someone can cure my stuttering someday so I can get a job and support myself in the future. Amen.”

In the short time that took, probably less than two minutes, Edward turned around to walk the old man back to San Francisco, and, just like what happened at the hot dog stand, the old man was gone! Edward looked all up and down the straight walkway of the bridge and could not see him anywhere. He looked over the side to see if the man might have slipped and fallen himself. He looked across the lanes of traffic to see if he had somehow darted across to the other side. He asked strolling tourists if they saw an old man with a beard and long hair in an old gray overcoat running toward San Francisco, but no one seemed to have seen him.

Edward returned to spend the night in his well-hidden spot in the bushes and trees of the Palace of Legion of Honor. Edward had left a note on his sleeping bag which said, whoever found it could have it, as he would not be needing it any longer. He was glad it was still there as the drama of the day had worn him out. The reality was beginning to set in Edward’s mind, as to how close he came to ending his life that morning on the bridge.

It took him an unusually long time to get to sleep that night as he kept trying to figure out how that old man got away from him so fast on the two times when he was trying to get him fed. It was a big mystery he could not figure out no matter how much he thought about it that night. For a second or two he even entertained the idea that the old guy might have been an angel, but he dismissed the idea, saying to himself before he went to sleep, “Angels don’t look like him…Angels wear white robes and have wings…”

Then he wondered if there were even a remote possibility he might find someone who would cure his very serious speech impediment, as the old man had promised. Edward finally dismissed this notion as well, as too good to be true. Just before he was finally able to close his eyes for a long sleep, he came to realize that the whole day was a miracle. He had not ended his life, which he had been clearly hell bound to do.

When Edward woke up the next morning, a strangely wonderful feeling came over him as the dappled sunlight hit his face. His deep depression, for some reason, seemed totally gone. He actually felt hopeful that he was going to have a decent day without dark thoughts for the first time in weeks.

Part 2

Edward auditioned for a funeral organist job at St. Francis Lutheran Church, on Church Street in San Francisco, just down from the San Francisco Mint. Rev. Kangas, the pastor of the church, told him, “Many folks have been born, married and buried through this church. You are the best amateur organist I’ve ever heard, and your playing could help our flock through these times. I can’t pay you what you’re worth but I’ll give you what I can from the collection plate.”

Edward agreed. This was a Norwegian church, so he borrowed the hymnal so he could learn their music. Though the money was not enough to get him a room at the YMCA in Berkeley, this would help him get by. Edward played his first Sunday service at the church two days later, and after the Reverend paid him out of the offerings.

He got a bus back to Berkeley where he attended a free event at People’s Park where a couple of local rock bands were playing for a student protest group. Edward enjoyed himself although he preferred classical, country music and jazz, to rock. He had enough money to drink several cans of cheap beer during the performance, and stayed off by himself a distance away from the crowd, so no one would have to hear his stuttering speech. After the crowd left, Edward was sleepy after drinking several cans of beer. When he woke up in the late afternoon the big crowd had gone. He sat on a park bench and started to read a book he brought with him in his brown bag along with a sandwich he had forgotten about. While he was reading and eating his sandwich, a student came up to him to get a light. The student tried to engage Edward in some conversation about upcoming protests in Berkeley, and of course, Edward could only reply in his usual halting stammering speech.

A thin, short old man was walking by him at the time. Edward noticed that he was short and thin, and had to drag one of his legs behind him and walked with a cane. He had a well- trimmed mustache and goatee. The man stopped nearby, waited till the other young man left, then sat on the other end of Edward’s bench.

“Good day, my name is Milton.” The man was a psychology professor and therapist from the Midwest staying with a U.C. professor friend in Berkeley, close to the park. He was giving lectures and doing research at Stanford University. Milton came straight to his point. “Son, I notice you have a serious speech impediment. I have developed some revolutionary ways of curing folks with problems such as you. With hypnosis and therapy. I’m sure I can cure your stuttering and stammering speech if I could work with you long enough.”

Edward was taken aback by the man’s bluntness, but could not help but think of what the old man on the bridge had told him. Sensing Edward’s discomfort, Milton explained that he too had a handicap—one leg was crippled due to childhood polio. He assured that there would be no charge and after some discussion, Milton finally gained Edward’s confidence. They walked to the apartment where Milton was staying so they could begin treatment. At first, Milton just talked with Edward to get him to tell him about his childhood history.

Edward spoke of his mother, who had told him for years that no girl would ever want to go out on a date with him, or go to a school dance with him. “Why would you want to ruin a girl’s chance to go to a dance with a good-looking boy with an athletic build, rather than someone like you, that is skinny and nervous all the time, and can’t talk right. They would just go out with you out of pity!”

These self-perceptions were deep in Edward’s mind, as his mother would tell him every year just before these dances he very much longed to attend, “Why don’t you just stay at home and read a book, since that is all you are good for anyway?”

After an hour or so, Milton was keenly aware that Edward’s self-esteem was extremely low from negative conditioning from the foster home. “I suspect there is more to your story. Such as regular beatings and verbal abuse? Yes? What is the worst incident you can recall?”

Edward haltingly told Milton about the time his foster Dad had gotten very angry at him, and in a fit of rage, threw Edward off the wooden piano bench he was sitting on in the kitchen. He then he hit him over the head with the bench so hard, it split the bench apart. Edward saw double and triple for a week or so and had to stay home from school because he had such bad headaches. He still had a small dent on the top of his head where a big egg had built up. But, he said, the worst hurt he ever experienced was when his foster Mom burned the 165 short stories and hundreds of poems he had written from the time he was eleven to sixteen years old.

“That was the one thing that hurt me worse than the bench busted over my head. Mister, I knew at that moment I had to leave that house or go crazy.”

Milton explained to Edward, that there was literal scar tissue on the Hippocampus of his brain from all the traumas he had been subjected to and that he could not remove those traumas. He explained to Edward that he could would be using hypnosis techniques to literally create a new reality for his subconscious mind to accept, which would include a new way of speaking, with lots of positive re-enforcements.

Milton was fascinated and wanted to use a tape recorder to record their hypnosis sessions, and even though Edward was averse to the idea, he finally agreed to it.

“You see, Edward, you have been told over and over again that you were stupid, clumsy, and hopeless, and other negative things that your brain has accepted as fact for years. I believe that you have dyslexia, which has hampered your confidence, and your scholastic progress. You are actually a highly intelligent boy. The fact that you wrote all those stories and poems! I suggest that your foster parents were stupid for not recognizing your underlying intelligence, and encouraging it. I am already starting the process of changing your perception of yourself, but it will take time and a lot of work to get the desired results. Unfortunately, we do not have it.”

At Edward’s look of dismay, Milton explained. “My work at Stanford is finished in only six weeks. I have never worked with a patient this quickly. But, we don’t have much time and I believe in you. This intensity and frequency will be challenging for me, and you as well. Thus, I must teach you how to hypnotize yourself so you can continue the techniques. Once you can induct yourself and use the suggestions and techniques, you can continue to improve your speaking abilities, even after I have to return home.”

Week 2. Milton was very experienced at inducting patients into a trance state, and he used a Zippo lighter in this process. He first had Edward lie down on the sofa, and would tell him, “My voice will go with you on this amazing journey we are about to take.” Edward was to focus on the flame of the lighter. Milton told Edward to relax each part of his body, starting with one foot, with every breath he took.

Milton had him notice his breathing and how it was getting steadier and relaxed as the total relaxation moved up to the lower part of the leg and so forth, till all parts of the body were being induced to become increasingly relaxed, one by one. Soon, Milton told him that his legs were so relaxed and calm that he would not be able to move them. He continued these gradual relaxation suggestions until Edward’s entire body was in this condition of total relaxation. He even suggested at one point that his body was becoming lighter and lighter, and felt like it was ready to float up off the sofa.

Week 3. When Edward’s eyes closed and his whole body was in a total state of deep relaxation and calm, Edward was instructed to visualize a television screen. “As the TV set is turned on, you will see yourself appear on the screen. See yourself in an idealized condition of looking good, and being dressed well, the way you would like to see yourself. Do NOT look at yourself much at this point, because you have a low opinion of yourself. Instead, focus on two people, a man and a woman, real or imagined, what these people are wearing, and what they look like.” Soon Milton continued, “Add color and detail to the scene. On your TV anything is possible, and on this program, you can see yourself speaking absolutely normally, and smiling and feeling good about yourself. Now, focus on this couple as they acknowledge you, smile at you and say much they enjoy talking to you.”

Positive re-enforcements and praise were said by these two people, although Milton’s voice was taking over their speech. Edward intently watched and listened to their favorable reactions. After this first encounter with this process, Milton told Edward, “You will wake up and go into the bathroom, and splash cold water on your face. The second the cold water hit your face, every cell in your body and brain will embrace and accept the new reality as you see on the TV screen.”

When taken out of the trance, Milton explained to Edward, that it was natural for his conscious mind to initially try to reject some of the suggestions as contrary to his years long negative perceptions of himself. He told Edward that by repeating the exercises over and over again, that he would eventually be convincing his brain to accept the new way of speaking, because he was getting such good feedback and reinforcement that the brain much preferred to the old perceptions of people NOT liking how he spoke when he stammered.

Milton continued to stress to Edward both in conscious conversation and subconsciously during trance, that his foster parents were wrong in the way they beat him so many times with wire coat hangers and boards, and that they were totally wrong about Edward being a mental case or stupid. Milton used many techniques with Edward which began to change his entire self- perception.

By the end of the third week of these strong suggestions during the trance state, a marked change came over Edward. His spirits seemed suddenly much better, and he was gradually able to speak nearly as well as the images he saw on the TV screen of his mind, as he continued to focus on various people telling him what a good speaker he was, and how intelligent he was. There were even suggestions to Edward that he was a good-looking boy, which was very hard for him to believe.

Week 4. Milton told Edward a good analogy for this exercise. “Edward, your low self- perceptions are like a saw stuck in a bind. “What would you do if you were sawing a tree limb, and your saw became stuck in a bind?” Edward responded that he might get the saw out of the bind and start a new place to saw.

“When you start a new place to saw,” Milton said, “often the saw will slip out of that new place you’re working on and slide back into the old bind. The process of continuing to keep trying the new spot on the wood till a new groove was possible, is similar to the conscious mind at first rejecting the positive suggestions as not being what you have perceived yourself to be, for so many years of negative re-enforcements.”

Edward asked Milton why he was insisting that he use the TV screen image in his mind, and Milton pointed out to Edward that if he gave him an open space in his mind to see these things, that his mind would wander and it would be difficult for him to be receptive to the new positive re-enforcements that seemed unreal at first.

Milton said, “Whether you know it or believe it or not, you have already been conditioned for years to believe strongly anything you see on the television. The advertising industry creates new suggestions in your mind that you have already acted on as a result of mind manipulation. The ad folks on Madison Avenue have used the television medium to get you to want and buy brands of soap, razors, toothpaste, beer, soft drinks, clothing and many other things. Edward, because of the years long influence television already has on you, the suggestions my voice is going to make during the hypnosis, are going to be much more powerful and readily believed, and get quicker and stronger results, than if I instructed you to only use a borderless space in your mind.”

Edward understood the logic of this, and allowed Milton to continue these sessions nearly every day that Milton had time for him.

Week 5. To speed the process up and make Edward more susceptible to quick induction for the sake of time efficiency, he had Edward practicing deep relaxation and self-inductions at home as often as he could. Edward began to believe that something could come of this, but as Milton had told him, the secret was time and the repetition of the suggestions and triggers. He began to regress Edward back in time while totally inducted, and got Edward to remember things his conscious mind had forgotten. At some point Milton had successfully regressed him back to when he was only six months old.

He drifted back: It was a warm summer day in Berkeley at that time, and when Milton stopped the induction, Edward found himself on the floor where he had rolled off the sofa. Milton explained to him that he must have hurt his head falling somehow, and that he was in a cold place where he felt he was freezing.

After the session, Edward was so perplexed, yet encouraged he worked up enough nerve to ask his aunt. His foster mother’s sister. He found a pay phone and called. She knew right away that he was different. He told her that he was working with a therapist and making good progress. He needed some answers to help with the therapy. He told her about his regression vison.

She said, “It’s time you knew. You didn’t hear this from me. A baby was abandoned by his birth mother on a back pew of the Church of All Hallows.”

Edward knew where that was—in the poor Bayview District of San Francisco.

“The poor little thing was found the next morning, on the floor, with his blankie slipped off. Hypothermia had set in, and he was rushed to San Francisco General. The baby bottle was found be filled with orange juice, and gin. It was assumed given to him to keep him quiet. The baby almost died.”

“Oh, oh, oh…” Edward said.

“The baby was turned over to Catholic Social Services. This all turned into a big scandal involving the priest at the church. The Bishop was so mad, the priest actually went into hiding in the basement of St. Ignatius Church. You see, Edward, the mother was believed to be a, well, a ‘night worker’ at a local bar. She was doing what a girl had to do in a bar that she lived above. She would tip the landlady for sticking a bottle in the baby’s mouth if it cried a lot, while she worked…”

She paused for a moment. “So, Edward, the baby was believed to be a “gift” to the Father. Your father.”

Edward had suspected that was coming, but he still gasped.

“And the Father, that man was the best organist the church has ever had!”

Edward’s hair stood up on his arms. He dropped the receiver, dangling, stumbled away to the curb, and sat heavily, his head in hands.

Milton became more successful in gradually changing Edward’s perceptions of himself with each intense hypnosis session. Milton noticed that Edward started taking better care of himself, and started bathing regularly and washing and combing his hair, and wearing more attractive thrift shop clothes. Milton would complement him every time he saw any improvements like this, knowing that a spirit like Edward’s, that had been so beaten down for years, could not get too much positive feedback.

Edward noticed that he could now look himself in the mirror without hating what he saw, and had gained a degree of self-assurance he could never have aspired to in the past. He became more cheerful and in better spirits the more these sessions went on with Milton. He even cut down on his drinking by the time a month went by. He was excited that the experiments Milton had given him where he talked well of himself in the mirror at home was working. He was stammering and stuttering less and less with each session with Milton. Soon his speech could be near-perfect for several minutes at a time. Edward eagerly kept up the mirror exercises realizing he would be able to speak normally sooner than he thought possible. Milton kept up the positive reinforcements and triggers during trance with more results being achieved at a faster pace.

Edward knew this was nothing short of a miracle. At several stages of this progress, Edward’s memory went back to that fateful day on the Golden Gate Bridge, when that kind old man talked him out of what would have surely been a completed suicide, and told him of a day in the near future when he would meet someone who would change his life forever. There was no doubt in Edward’s mind at this point, that it could not be just a chance coincidence that he met this professor who was visiting Berkeley. His thoughts often grappled with the notion that, rough as he was in appearance, the old man might indeed have been some sort of angel without wings sent in an old man disguise? How else he wondered could such events be predicted by someone and happen just by random chance?

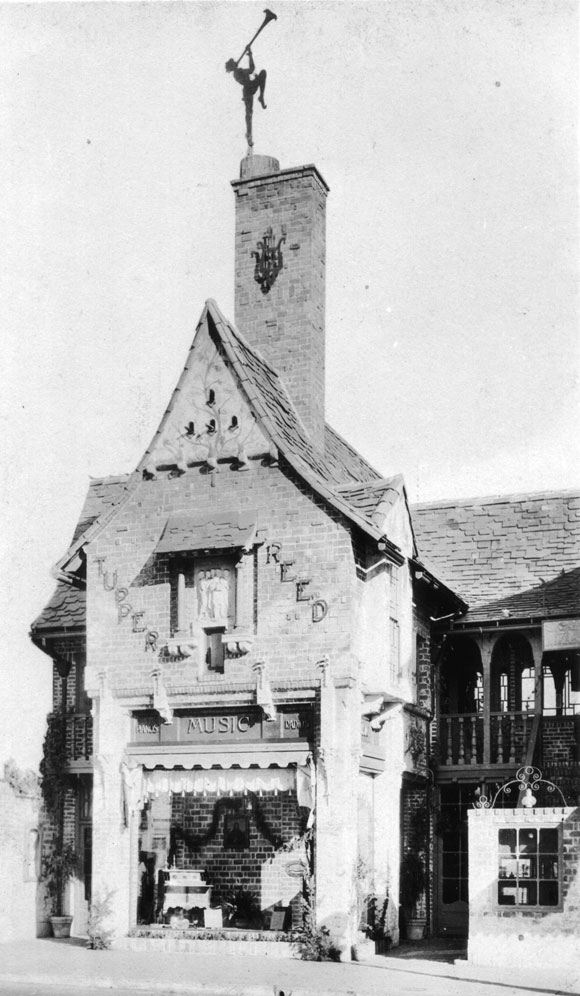

A little after five weeks of Milton’s treatments, Edward realized he could speak well enough to get a job that he actually wanted and could enjoy. He had previously applied to the Tupper & Reed music store on Shattuck Avenue but was rejected more than once. He was certain it was because of his manner of speaking. He went into the music store one again, only this time he dressed well, and was shaved and groomed with a nice haircut. When he talked to the owner who had rejected him numerous times, the man did not even recognize Edward. He explained to the owner that he was indeed the same person, but that he had been taking some recent therapy that improved his speech abilities and that was why he was not recognizing him as the same boy. Edward told them he would like to sell pianos and organs, but the owner said he was too young for that, but he’d be willing to try him behind the small musical instrument counter selling band equipment, flutes, guitars, and sheet music.

Week 6. Edward eagerly accepted the paid full-time job, plus a small percentage of sales as a bonus if he exceeded his sales quota.

Edward wanted to take Milton out to dinner, but at the apartment, Milton’s friend explained that Milton had already gone. He had to leave early for a family medical emergency. His flight time had left no time to say goodbye. The man handed Edward a short note from Milton expressing his pride and confidence in Edward.

Edward was very sad that he had no chance to show his personal thanks to this amazing man. A man who was so small in stature, with a polio disability. In Edward’s eyes Milton was a giant of a man who had the power to change Edward’s seemingly helpless and hopeless life to one of hope and promise. Edward was certain that Milton was the very person the mystical man on the bridge had told him about. Then wasn’t Milton part of the plan from the Lord himself?

Edward went out that night alone, in his sports coat and tie, and dined at Spenger’s Fish Grotto, at the foot of University Avenue. This was a Berkeley landmark, known for excellent seafood and cocktails at a reasonable cost in a classic nautical atmosphere. He felt so naturally good, he did not even have a desire for a drink. After dinner he walked confidently onto the nearby Berkeley Pier. There, he had occasionally dropped a line to catch his own fish dinner when he first left home.

The mile-long pier looked straight out to the Golden Gate Bridge. As he observed the ships come in and out of port, and the expansive view of the Bay and San Francisco, the city of his birth, a feeling of joy and peace came over him like he had never experienced. The sun seemed to quickly set, the lights of San Francisco twinkled on, and the Golden Gate Bridge began to show off her necklace of amber lights. In that moment, old memories of his traumatic past in the foster home, quickly gave way to newfound feelings of hope and confidence for the future, Edward could not have remotely imagined a mere two months before.

END

Read our interview with the author Scotty DeWolf here.

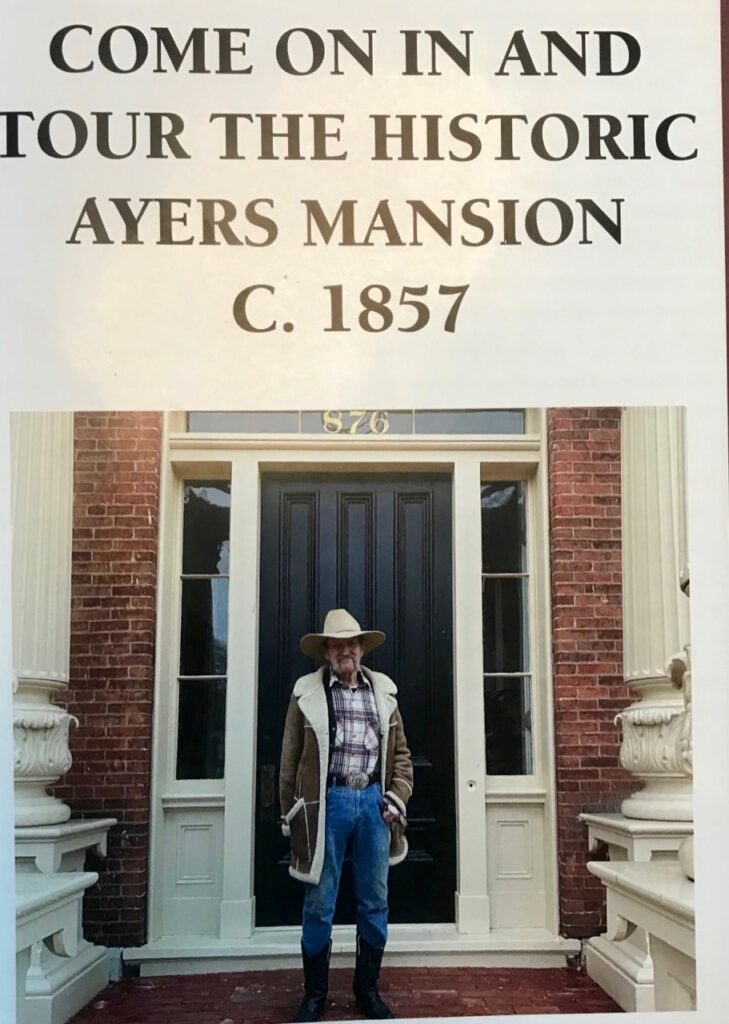

Note from Scotty DeWolf: I am raising a final $150,000 to finish restoring the mansion so we can open up the bed and breakfast business which will become an economic engine to sustain the “Esprit de Corps Academy.” Our mission is providing FREE music and performing arts education here in Jacksonville and many of the surrounding small farming communities who lost their program funding when the State of Illinois’ budget was in recent crisis. This non profit will also outreach to seniors here to keep them engaged in learning new things and staying mentally active. Make a PayPal online donation at

See Scotty’s FaceBook page. At the FB search bar or GOOGLE, enter: “Facebook Villa DeWolf B & B.” Scotty DeWolf in PBS “Illinois Stories.” Illinois Stories DeWolf B&B WSEC TV PBS Springfield

From previous issues:

Issue #19

From Susanna Solomon, frequent MillValleyLit contributor, fantastical musings of Parisian imagination and delight debuted here. This is the final story from her upcoming third short story collection, Night Train to Paris. Window photo by author.

The Teddy Bear

My name is Ezra Pound. I’m a teddy bear. As you can see by my faithful companion, my typewriter, I’m a literary type. Do not be disappointed, this cardboard box is only a temporary friend. My garret is in the 16th Arrondissement. I could tell you that my studio is being painted, but the truth is, it’s hard to climb the stairs up to the second floor. Fortunately for me, Monsieur Souvien, the owner of this store, has made me welcome. So my new home is in this window.

Pardon me for avoiding your eyes, Madame Nina, and staring off into the distance but a beautiful woman is walking down the street—heels, fur coat, of course sunglasses, and a large hat with an enormous red ribbon. I can’t take my eyes off her. If I offend you, I am sorry. All the beautiful women come down the street in this direction. Not that you are not beautiful, Nina, but those young ladies, those mademoiselles, they do draw attention, do they not? Sometimes my neck gets stiff. Enough about me. What about you?

You’re from America? Tourist or expat?

Oh, I see, tourist. Merveilleuse.

You spend your days looking in shop windows and taking photographs. What an odd idea. When I was much younger, the shop windows were quite pretty with snow scenes, miniature people, horses and carts, and sometimes trains. But this shop has been bought and sold two or three times over the generations, so we’re left with these dumb cardboard boxes. But I’m here! Pretty? Maybe not but interesting, n’est-ce pas?

Certainly, you’ve noticed that I’m a bit chubby? You think all teddy bears are chubby? Not true. Once, a long time ago, I was skinny—no reason to imagine it, you’ll make me feel bad—but now, more round. Madame, with me you see what you get and I get tubby. I don’t get out much.

I’ve had a tough life. I do not ask much of you, but please, listen, just for a minute or two. I haven’t always lived in a window. I got in with some shady characters years ago—they wanted my soul! Of course, they couldn’t find it, so they took out my heart instead. I can be loved, but I can’t, shall I be so bold as to say, love back. Shall I show you the scar? No. Never mind, then. Fur covers a multitude of sins. But they broke me when I wanted to leave them. Teddies are a loyal bunch, as you can imagine. All that cuddling!

Anyway, after I relieved myself of command as leader of the bad boys, I went to the States, where they imprisoned me. They called it a hospital, I called it a prison. I couldn’t leave, so what else would you call it? I went crazy! I had no choice, mind you. At the hospital, after many years, they finally let me go. For whatever reason, I can’t tell you—only that maybe they gave up on trying to make me sane.

Then I came back to France and tried to contact the new leaders of the bad boys, but they turned their back on me. And laughed. And now, I wave at the pretty girls and wish I could be proud of who I was then, but I cannot.

No, I was not a teddy bear then. They say poetry makes the man. I’ve written a lot of poetry. But I’ve never looked to help my common man.

God has a weird sense of humor, don’t you think? And he loves teddies. Do you think he’s a Steiff man? Well, I don’t have a clip in my ear as they all do. I have only this scar. Oh no, don’t worry, they gave me back my heart. It’s just changed, somehow.

Let me tell you a story. It was late, in Paris, the night I left my garret with a sheaf of notices—broadsides—created by the bad boys. My job was to distribute the flyers all over Paris, plaster them to lampposts, fences, stone walls. I had a bottle of paste in one hand and a hundred missives in the left pocket of my great coat. Yes, I needed my coat; it was very cold.

For some reason, I found myself down on the quai by Canal St. Martin, a place I don’t recommend for the safety-minded. It was getting dark, but the lights weren’t on. Another strike—you’ve heard of them in Paris, I’m sure. I was pasting these flyers along the walk and nearing the tunnel and locks leading to the Seine. I turned back to return up the stairs whence I’d come, a pair of eyes watching me from the bridge above. He was dressed all in black, like a cat. Coming through the tunnel were several other men, wearing watch caps and coming my way. I headed back up the quai, shoving my hands into my pockets, trying to keep the papers from crinkling and making noise. There were no indentations in the stone wall alongside the quai. No place to hide.

Two men were walking down the stairs. I froze. That made three. And me. A mere poet! A firebrand, but a poet, nonetheless. Two more of them now and I was surrounded. Five against one! They started closing in before I could get it all figured out.

“Pound, Ezra Pound,” I said, putting out my hand. I could talk the legs off a gazelle, if they gave me a chance, but they all spoke at once and came in for the kill. One grabbed my great coat, another the glue, and a third another found my leaflets.

One of them, the largest, turned me around. “No care for the little man, eh, Pound? Fascist pig.” He spat.

They spun me until I was dizzy. Then they splattered the stone with glue and pressed my face, hands, and body onto the cold sticky wall.

“We fought the war to kill all you fascists, yet here you are. Cover him, boys!”

They painted me all over with glue and covered me with flyers. The largest one even took my shoes and socks and glued my feet to the pavement. Then they all ran.

That was a dark night for me—shall I say, my darkest? The glue hardened quickly. My face froze. My hands and bare feet lost feeling. I grew stiff and the pain from not being able to move was unbearable. I cried out for mercy. I cried out to God. At two in the morning, I fainted from the pain and fear. When I woke up, everything was worse, if that was possible. At four I fell into a fitful sleep.

At five, still dark, soft hands touched my shoulders. Whispers filled my ears. Soft caresses. Hands ran over my back, soothing my muscles, though other hands were exploring my pockets. I waited impatiently for my long-deserved freedom. Only a minute, two at most, I could wait for my prayers to be answered.

Two minutes turned to three. Their voices hushed. Sunlight started to break over the tunnel. They were gone, my wallet and money with them.

God came with the sunlight at least. He said he was God. Who was I to disagree?

“I’m not a bad guy,” I said, “just a poet.”

“Well-known for treason, Ezra Pound,” God said. “Honoring fascists.”

“They’re friends of my sister’s. They said they loved me,” I stuttered.

In the approaching light, God didn’t look like what I’d imagined. Of course, he had long hair, a long beard, and a robe. But hairy feet? I was surely delusional by then; I imagined his sandals were fur.

He placed his cool hand on my forehead. It was soft, like a baby’s, covered with fuzz.

“I’ll free you if you relinquish their world of hate,” God said, cackling.

That made me feel very peculiar. I didn’t know God laughed—at least not like that.

He pressed his palm against my face, softer now. “You’ll be all right, Ezra. Just breathe normally. This won’t hurt a bit.”

To remove me from my sticky prison would hurt a lot, I was sure of it. I’d been there all night and would be there forever if he didn’t release me. I winced.

An arm around my waist, a whisper in my ear, and pop. I was free of the wall. My skin stung as feeling returned.

“No more broadsides,” God said, looking at me. His eyebrows were so thick. Fur burst from his ears like one of my teachers in grade school.

“How can I thank you, my Lord?” I asked and kneeled.

“You are one of God’s chosen ones, Ezra. You may go free now.”

As I stood up, I almost fell over. I’d always been a svelte man, but now I had a big round belly and I had to lean back a little, to keep my balance. What had happened to me?

“I always take a little for Myself,” He said, walked toward the water, and disappeared.

The sun was casting bright rays down the cobblestone quai. Flyers were stuck to the walls at odd angles, but none were stuck to me. The wind was up, making them flutter. I went to pull one from the wall, but my hands were different now; they didn’t move like before. Was it the glue? Fat brown pads had formed where my fingers had been. I could barely grasp the papers, much less pull them free.

I squinted at the sun, looked down the quai and toward the stairs. My legs, once long and lanky, were now stubby and covered with fur; I would never have the strength to climb those stairs.

I ambled down the quai anyway, toward the tunnel, toward the Seine. I remembered the ramp from my walk earlier in the week. I could do a ramp. Half-way into the tunnel, fatigue overcame me and I sat down, much as I am now, and rested. For a day and a half, or two days, maybe three, I sat there. I lost track of time. At some point, Monsieur picked me up.

“You poor bear, you poor teddy bear,” he muttered and held my hand tight. He picked me up and gave me a kiss. “Would you like to live in my window?” I’ve been here ever since.

END

More from Susanna Solomon follow:

The Clock

by Susanna Solomon

The third day I was in Paris I hopped the Metro back to Musée D’Orsay. The building was huge; once a train station, now it was a museum. Glass ceilings soared above me. Balconies and stairways led every which way. A gigantic clock, which I’d missed last time, hung outside the window at the front of the museum, just outside the third floor.

You could see all of Paris through the back of the clock. Haussmann buildings, across the river, rose behind the Roman numeral VI. A few tourists looked out the window in front of me. The numbers were backwards, of course, because the clock was supposed to be read by people outside, coming to the train station, not by people inside the building looking out.

It was raining. People were milling about, waiting for the rain to stop. And then they were gone. I took my place behind the VI and looked out at the misty Seine below, at the mansard roofs across the river. I imagined walking through the clock and traveling back in time.

What would it have been like?

To be there during the revolution when the streets were full of blood? To hear the German jackboots pound the streets as they marched to the Arc de Triomphe? To wave American flags from open windows on the day the Americans arrived in their tanks, trucks and jeeps?

I had been a little girl then when Maman pressed a small American flag in my hand. Everyone was lining the streets and cheering as the tanks rolled by. We’d been down so long. I held Maman’s hand tight and looked up. Tears ran down her face. She had tried to protect me, but I’d seen the grim lines of hungry people, the soldiers returning from war, leaning on their wooden crutches, desperation and despair filling their eyes. And I remembered our butcher, Abe, and his family disappearing. Maman had prayed every night, and I with her, my knees on a threadbare carpet in front of the windows, listening to Voice of America.

And back further? I could see through the rising mist, through a dark cloud which dissipated. When the plague came, we were poor and didn’t have the option to move out of the city like so many of our neighbors. Our house was stone, at least, but others, who lived in wooden structures, their homes had been burned down to rid the streets of rats. Two of my friends in our building had died, and Aunt Renée’s baby Ruth was in the worst way and was not expected to live. Why I was spared, I’d never know, but as I grew up, we left our memories behind. No one wanted to think about the time when Paris lost 30% of its population. It took years until I stopped having nightmares about seeing wagons full of bodies roll through the streets.

The clock in front of me clicked as the hour hand slid to 5 p.m., while the minute hand, at least ten feet long, eased along behind. I looked through the glass again. I could see myself, as a young girl, running in the park across the river.

“Come on, Amy! Follow me!” my cousin Jean-Marie from Lycée Fénelon waved me on. We were walking hand in hand in the Tuileries, our mothers fifty feet behind us. Jean-Marie held a ball, a red one, and gestured for me to go back, to run back so she could throw it to me, and I ran, as fast as I could and turned. But Jean-Marie was gone.

“Jean Marie!” I called. I saw no one.

I ran back to where we’d separated. “Jean Marie!” I yelled, but no ten-year-old girl with braids was in sight, just an older couple, walking arm in arm under some mulberry trees.

Fighting rising panic, I ran around in all directions, hollering her name. There had been news in the papers about bad guys kidnapping girls and chaining them up in crates. Had they already grabbed Jean Marie? I ran back, back to the picnic bench where we’d started, eager to find the moms.

The ground beneath my shoes sounded like sandpaper as I ran. I didn’t remember running so far away from my mom and her sister. Had they been standing under this tree? Or that one? In the open or in the shade? I moved fast, covering ground, yelling Jean-Marie, Jean-Marie, until my throat got sore and I just yelled “Maman! Maman!” and that’s when I saw them, our mothers, sitting on a bench. My mom and her sister Francoise who was pushing a stroller back and forth with her feet. I ran closer, panicked. They would blame me, they’d call the police, and horrible things would happen to Jean-Marie.

“Amy!” my mother stood up straight, dropping her knitting on the ground. “Come, Amy. Come, she’s here.”

I ran into my mom, driving my head and shoulders to her belly, and she held me, close, close, as my cries turned into big hacking sobs. “She’s here, dear, right here, don’t worry so, my darling,” Mama said and Jean-Marie came over and held me too. “You had such a scare, my sweet.” I couldn’t stop shivering.

“Everything’s okay, sweetheart,” my mother said and held me for the longest time. My heart was pounding, my hands were clammy and cold, but Jean-Marie was fine. She held the red ball and looked at me with kind eyes. People on benches nearby shook their heads, while a group of Parisian teenagers, all girls, gossiped and laughed as they walked in the open, and I held Mama closer until I felt better, a little bit. It took all day, two cups of chamomile tea and cinnamon toast, two slices, before I felt like myself again.

I backed out of the clock. I’d been in Paris with my own mother, years ago, and she had been wearing her shirtdress as usual. We’d walked the Quai, checked out the books at booksellers along the way, held hands as we crossed streets, and I, so much smaller, had to run to catch up, until she was gone, really gone, and I had been fourteen.

The big clock struck six. A guard came up behind me and said, “Madame, nous fermerons maintenant, we are closing. Merci, Madame,” and I followed a few people down the escalator, out the lobby and into a drizzly rain. I walked around and looked at the giant clock. It was so high up there; I could barely see what time it was, but knew it was time to go. Tomorrow, perhaps, I’d come back, step through the clock, and once again be in my mother’s arms.

END

Susanna Solomon’s stories have been published both on line and in print in literary journals and in two short story collections, Point Reyes Sheriff’s Calls, and More Point Reyes Sheriff’s Calls. Her novel, Montana Rhapsody, sets an LA savvy pole dancer and a farmer in a canoe deep in the wilderness on the Missouri River in Montana where their trip does not work out quite as planned. Currently at work on her absolute favorite – a collection of short stories – called The Night Train to Paris, she hopes to have out in a year or two.

Susanna Solomon’s short stories can be found on line (Harlot’s Sauce Radio, The Mill Valley Literary Review, Foliate Oak Magazine), in print, The MacGuffin, Meat for Tea – The Valley Review, and, Shoal, the Literary Journal of Carteret Writers. Videos of her readings can be found online, in five years of Redwood Writers Anthologies, and in The Point Reyes Light. Susanna is an electrical engineer and has owned and operated her business for twenty years.

Photo credits: Musee clock—web source. Susanna reading, Paris clock—J.Macon King.