Get comfy and let our LITERARY LATTE stimulate your intellect and emotions.

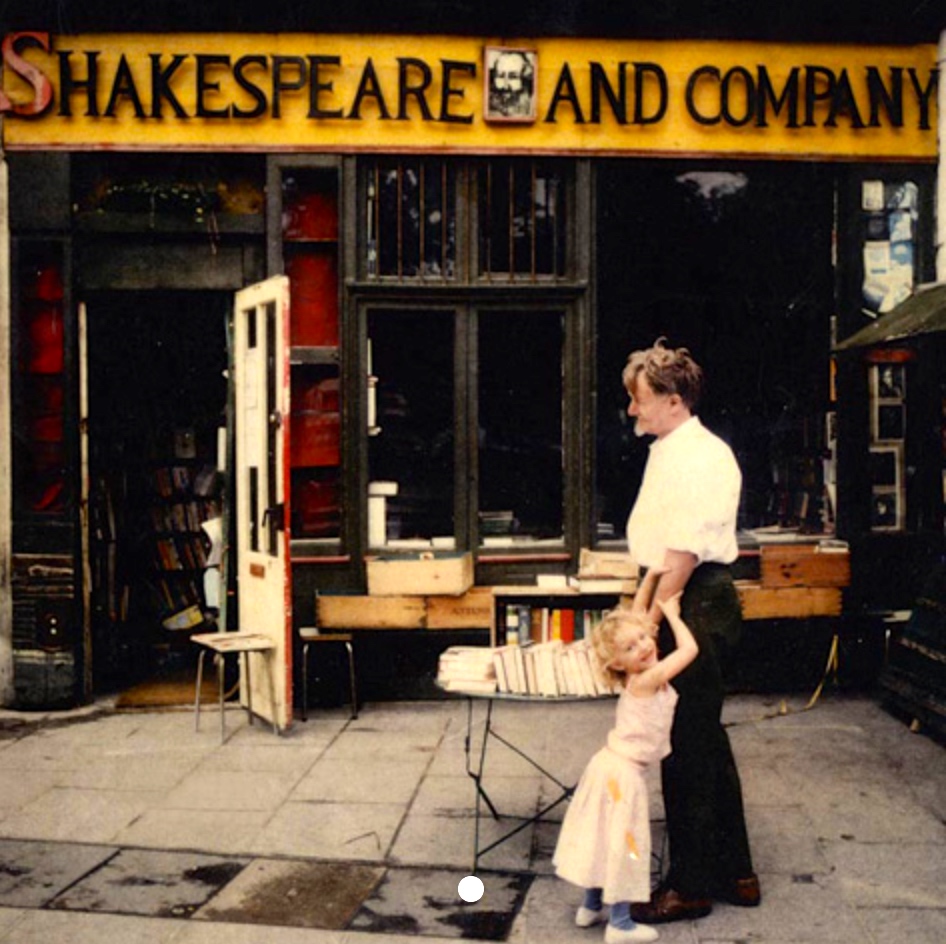

SHAKESPEARE & COMPANY

short fiction by Susanna Solomon

“No, it’s true, I used to live here,” he said with a grin. “Just upstairs.”

“You used to live in a book store?” I asked.

“Can you think of better company?”

I ran my hands along the spines of the books tucked under a staircase at the back of the bookstore, Shakespeare & Company. In Paris. I was there for a week and it was my second visit.

“Name’s Tom,” Tom said, extending his hand.

“They have bedrooms upstairs?” I asked. “An apartment? A studio?”

“Of sorts.” Tom laughed. “Two beds and a fold-out Murphy bed. People stay here for years.”

“Windows?” I asked. I don’t like small spaces and was feeling a little too tucked in at the back of the shop under the stairs.

“A view of the Seine,” he said. “And Notre Dame.”

“Good Lord,” I answered and sat down on a stool.

“You have to ask gently, and not be aggressive in any way. It’s like anything – if you make yourself a pest. There’s a fine line. I wanted, I asked, I got in. Took two years.”

“And now?” I answered, thinking of the comfort of my hotel room with the ensuite bath.

“All you have to do is stack shelves for two hours a day, and read a book a week,” Tom answered, making space on a shelf for two paperbacks he held in his left hand. “But there are stories.”

“Ghost stories?” I asked. Paris or no Paris, sleeping in a bookstore would be fun. “Like Scott Fitzgerald, or James Baldwin or Hemingway?”

“Not at all,” Tom laughed. “A thin ten-year-old in a white nightdress holding a candle.”

“You’ve seen her?” asked an American girl to my left. Too many braces, too much hair color, but her literary appetite was good. Her hands were full of books. My books. For I was an author. I was going to stay silent this time. Tom knew who I was, but not the others, and that’s the way I liked it.

“Two years ago. After the shop closed at midnight. Fernando, the Murphy bed guy, he was out in the Marais, and as for the other resident,” Tom said resident, like res-i-dent, “he had just moved out. So it was just me. Mostly. I remember I was holding a cup of espresso in my hand.”

“You drink coffee that late?” I asked, scanning the owner’s picks. Why hadn’t they picked my books?

“Twenty-four hours a day. Coffee doesn’t do a thing for me – but doobies do.” He sighed. “But I hadn’t even struck a match when I saw her.”

“She was floating by the door?” I asked.

“On my bed actually.” He thought a sec. “Not quite under the covers. Standing over it, like apparitions are supposed to do.”

“A character from a novel you just read?” I asked. “Madame Bovary?”

“When she was twelve, Miss?”

“Mona.”

“Mona. It wasn’t Madame Bovary when she was twelve. No one knows what she looked like then.”

“Holding a croquet mallet.”

“I saw that episode of Endeavor. You’ve been watching too much BBC.”

“What’s not to like?” I asked. “Show me. Show me now. Upstairs. Just up there. Would the owners mind?” I gestured to the front of the store.

“If you buy at least three books,” Tom answered. He towered over me, but still, there were possibilities ….

“Now?” I asked. I wasn’t really ready to choose a book, much less three. “So, tell me, the ghost – “

“The apparition?”

I nodded, my palms sweaty.

“She was crying, sobbing quietly. I asked her why.”

“Tell me more,” I nudged closer.

“’If you’d been stuck in an attic a hundred years, you’d be crying too, buster,’ she said.”

“That’s kind of modern language.”

“Don’t you think she reads too?” Tom replied.

“I guess,” I said dryly, “for how can a ghost read a book, much less hold one?”

“She leaned toward me, I was trying to back up to the stairs – those stairs just above my head, then she stopped, held out her hand and spoke again. ‘Get me out of here, Tom.’ Upon hearing her speak my name, I practically fell down the stairs, they’re steeper than you think.”

“You’re pulling my leg,” I said.

“As she was pulling mine? Not hardly. ‘I won’t hurt you,’ she said. She was wearing a bright white bow in her hair like those photos of those Victorian girls you’ve seen.”

“’I couldn’t find a brush,’ the ghost said. ‘Pardon my somewhat disheveled appearance but there are no beauty supplies here, as you can see.’ She ran her hand through the air and sparks flew out of the ends of her fingers. ‘Guy stuff,’ she said. ‘No good for me. Don’t you guys ever bathe?’”

“How could I tell her?” Tom went on. “There’s a sink downstairs, at the back, and a shower at the Youth Hostel down the street, but – but. She scowled, wagged one finger at me, sending sparks. ‘You’re afraid I’ll be seen, if I go out on the Quai?’ I wasn’t sure what to say, so I sat down on the bed.”

“What did she do, then, Tom?”

“She sat beside me. About 4’-10”, her legs stuck out as her feet in her blue shoes were too short to set on the floor.”

“Did you touch her?” I asked. “Did she feel like fog? Or water? Or maybe jello?”

“And?” I asked.

“Mist, yes, that’s right. She felt like mist. Cool. Young. Beautiful.”

“And sad,” I added.

“How did you know?” he asked. “She had reddened, watery eyes.”

“Not from living a few hundred years too long?” I asked.

“No. From people asking her stupid questions.”

Oh, that shut me up fast.

“You’re the one who started it,” I said finally.

“We spent some hours together. She told me a little about her home in the 9e. The walk she took on her way past St. Sulpice, down the alley, the strong hands who grabbed her. She hadn’t planned on being out after dark, but she’d been playing with Sophie – and had lost track of time –“

“One of the Paris Rive Gauche murders,” said one of the onlookers. His face was lined, his body thin and wiry. He put one hand on the banister going upstairs. “I’ll protect her.”

“No!” Tom cried, pulling up his long form and pivoting so he was at the stairs, his one hand on the stranger’s arm. “She doesn’t handle visitors well.”

Just then an ear-splitting scream came from the front of the store. We all ran. Ten to fifteen of us crowded the front of the shop and pushed our way to the door.

“ça rien, it’s nothing. No one. A pickpocket. He was caught,” a gendarme said. I saw the cop cars, heard the woo-woo of sirens, and thought about the ghost upstairs. She could have used a gendarme that night. I was the first to reach the stairs while everyone was still at the front of the shop.

“Miss?” I called gently, hoping no one would hear the creak of steps as I rose. Two, three, four steps. “Miss?” I pushed open the door, expecting an apparition, a girl not even half my age, a girl who had never had a chance.

“Yes?” answered a voice, a man’s voice, a man with a week-long beard and a gravelly voice. “Customers aren’t allowed up here, Miss.”

I blinked my eyes. “Tom…he said,” I sputtered.

“Ah,” the unshaven man said. “You missed her by minutes. My ‘petit adventure,’ my lover, she had to go to work.”

“Not your girlfriend, kind sir,” I answered, heart pounding in my chest. The …” I felt like a fish out of water, couldn’t breathe, couldn’t get air.

“Ah. Thomas. Again,” the man sighed. “The apparition.”

I nodded. “You seen her?” I asked.

“In my dreams.” He sighed, walked toward me. He was very tall and looked down on my face, then shook my hand. “You are not the first, dear…”

“I should say not,” I answered.

His hand was dry and warm.

“We are in a monument to storytelling, Miss. A library for the greats. A place where dreams are made. Did Tom give you a dream? That you believed?”

I turned my face. I couldn’t look at him.

“Would you expect anything else at Shakespeare and Company? In Paris?” He grinned. “Come have some Kir Royale. You like Kir Royale? Or perhaps Absinthe? Come take a look from here. You are not the first, and you won’t be the last – but you are the prettiest.”

How could I resist? My own ‘petit adventure’. When I reached him he was standing by the window while the sun cast its last rays on the spires of Notre Dame. “I’m Georges,” he said. I was about to tell him my name when his lips closed on mine.

END

This Susanna Solomon story premiered in our issue 18, Fall 2020 and would later appear in her short story collection, PARIS BECKONS. Susanna is the author of several books of short stories. https://www.susannasolomon.com/ For another Susanna story see It’s Your Lucky Day.

More stories follow:

Winter 2022 Issue #20:

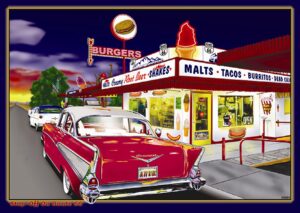

Death at the Drive-In Diner Dance

by Patricia L. Morin

“You always loved the old cars, Irv, and now we’re driving in one,” Rena said, then smiled over at Irv, white wavy wisps peeking out of his NJ Devils baseball cap, sitting tall and proud in their rented ’57 Chevy Black Widow. “Marv will love it!”

“I can’t believe we’re in Los Angeles, the land of tinsel and fake boobs. But, what a great idea Marv had for his fiftieth—a drive-in-diner dance. Who would think of such a thing?”

“Santa Monica, Irv. We’re in Santa Monica, land of skimpy clothes.” Rena opened the Los Angeles guidebook her cousin, Marv, had sent them with the glossy invitation. The Rocket Drive-in Diner was centered on the front, along with waitresses sporting short white skirts and black tops, rolling around on rocket skates, pale blue like the rocket on top of the diner.

“He’s cool, Marv, to invite us this bash.” Irv concentrated on the Pico Boulevard traffic.

“Yeah, he’s the bee’s knees,” Rena teased. “Listen to this. In the 1950s,” Rena read from her guidebook, “this style of building was called ‘Googie.’ I didn’t know that, did you, Irv?” Rena glanced at Irv, who gaped at a light-blue rocket ship that covered the whole roof of a long narrow building rounded at each corner and covered in steel with picture windows evenly spaced apart. “Googies include space-age designs, and bold use of glass, steel, and neon.” Rena placed the book on her lap. “And that’s just what we see now. Wow, must get my camera.” Rena reached behind her, where bulging camera and computer bags sat on the backseat, and pulled her new digital camera from the front bag.

The Elvis Presley song “Love Me Tender” resounded through the parking lot from speakers Rena couldn’t see. The smell of fried food permeated the air.

“Look!” Irv couldn’t contain his excitement, as he pulled closer to the diner. “There’s Marv’s hot Pontiac Chieftain! And look at that classy chassis! Man, can those waitresses move on those blue rocket roller skates. This vacation may rock.” Irv turned into the driveway and scanned the huge parking lot behind the building and the waitresses servicing the cars.

“You don’t have to emphasize every slang word, Irv.” Rena eyed the back screen of the camera and observed the world around her. Click…the pale blue rocket on top of the diner…click…a driveway of fifties cars with varying colors…click…Marv in front of the steel-and-glass doors with red and yellow stools behind the front glass—spotting them…click… Lisa, his wife, behind one of the stools looking at Marv…click…blond-haired waitress on roller skates…click…blond-haired waitress kissing Marv on lips…click…click…Lisa shocked…click…Marv stepping away from the blonde, waving to them as he approached their car…click…the blonde’s feet remained still while rocket roller skates moved on their own.

The song ended, and “That’ll Be the Day” by The Crickets replaced “Love Me Tender.”

“They don’t make cars like they used to, Rena,” Irv commented as he pulled the car closer to Marv. And the other classics.

“No, Irv, they don’t. That’s what I say about my cameras, too. Give me my old SLR any day, just not today.” She shook her head. “Remind me to show you some interesting photos later. Modern technology has its advantages.” She’d be able to manipulate every aspect of Lisa’s photo, as well as identify the other two people standing with her.

Marv had asked her to be one of the photographers, and she thought this would prove a welcome break from snapping pictures of dead people for the Atlantic City Police Department. However, live humans at a party proved more problematic than stiffs.

“Hey, Daddy-O!” Marv approached as Irv rolled down his window. “Nice chariot, a real hottie.” Marv shook Irv’s hand, then leaned against the window and smiled in at Rena. His black, straight, Elvis-like hairdo covered one of his dark-blue eyes. He flipped his hair back. “Glad you could make the scene. Everyone’s here.”

Rena lifted the camera from her lap. Click…Irv and Marv talking cars and guests. The Bluetooth icon appeared on the side of her lens. Click…Marv’s handsome features…click…a pretty dark-haired woman with a poodle skirt…click…off to the right, a lone orange car parked, a Pontiac Bonneville with big rear fins and a front grill that resembled a wide-eyed sneer…click…click…people gathering around several cars alongside of the diner…click…blonde kisser speeding toward lone orange car…click…close-up of face of blonde kisser…click…click…click…Blonde Kisser throwing tray up in the air as skates accelerate…blonde kisser screaming…click…blonde kisser tapping, then jabbing, at the smart phone on her waist.

“Oh my God, look at that!” someone cried from the driveway.

Rena gasped. Two waiters raced toward Marv’s blonde kisser. Marv took off after them. Click…blonde kisser bounced hard off the Bonneville and flew several feet in air…click, zoom in, click…landed on her back and slammed her head on asphalt…click…blood dribbled from her head.

Rena jerked the camera around to the front of the restaurant. No Lisa. She snapped photos of people running in different directions. She shot the entrance of the drive-in-diner, then shifted in her seat toward the back and side of the diner. The rapid-fire on the shutter button hurt her aching forefinger.

“Rena, did you see that?” Irv asked.

Rena set the camera on the dashboard and rubbed her fingers. “Call nine-one-one, Irv.”

“What happened?” Irv asked.

“It looked like the skates ran away with her.”

“What? How could that be?”

“I don’t know Irv, call nine-one-one! Then park the car.” Rena grabbed her camera and computer case. Sirens could be heard from several directions. “Never mind the nine-one-one, Irv. I’m going to inspect the scene.”

“Don’t get too close, Rena. You’re not at work. Poor girl! Poor Marv! His party didn’t even get started.

“I’ll meet you in the diner, just go.” Rena trotted toward the girl and Marv. The world stood silent for several seconds as Marv and Rena studied the lifeless body, her unblinking eyes staring at the sun. Oh my God, Rena thought, she’s dead!

The Platters sang “The Great Pretender” as tears rolled down Marv’s cheeks, and one of the waiters rubbed tears away.

The two young waiters gawked at the dead body, one of them visibly upset, the other not so much. She reached over Marv’s wide shoulders and hugged him. “I’m so sorry, Marv. Someone dead, and your party ruined. Horrible,” Rena whispered into his shoulder.

“Jesus, how could this have happened? My poor little Nellie,” he nuzzled into Rena. “This whole diner-roller-skate thing was her idea.”

“The police and ambulance are here. You’ll have to answer questions. I’m so, so sorry.” Rena ached for Marv.

The sirens screeched as the police and ambulance pulled into the driveway. Thinking and talking became unbearable. Marv stepped away from Rena, and she scooted past him and the two waiters toward the diner.

People congregated in the diner as if taking refuge from a menacing storm. The long row of red vinyl booths with aluminum frames were filled with guests staring from the windows and muttering over half-eaten burgers and ketchup-laden fries. The stools opposite the booths, mainly filled by younger guests, alternated in color from red to a bright yellow. The Teenagers sang “Why Do Fools Fall in Love,” the volume soft. Irv stood in a small circle of men and women near the entrance to the back room, where Rena eyed a wooden dance floor. She heard one woman wonder whether or not to go home or back to their hotel. Irv wanted to stay. Several women and men had dressed in ill-fitted 1950s garb.

“Where’s Lisa?” Rena asked Irv.

“You haven’t seen her either? Why didn’t she come and say hello?”

“I’ll go find her,” Rena said, then spotted college-age waiters and waitresses in the back of the diner, several sitting on the stools behind a big-screen Mac. She bet the music was regulated from that spot.

Sure enough, a surfer-looking man pushed a few keys and “Ain’t That a Shame,” sung by Fats Domino, filled the diner. How ironic, Rena thought. It was a shame.

“Hey,” Rena interrupted them. “I’m Rena, the photographer. Are these songs preset, or are you choosing them as you go along?”

“They’re pretty much preset by Marv. We just make sure everything plays well,” the surfer answered. “We’re monitoring the back room also.”

“Do any of you know about rocket skates? It seemed as though Nellie couldn’t stop them, and that they were taking her for a ride.”

The surfer-man furrowed his bleached-blond brows and looked at her as if she had given the word stupidity its meaning. “The waitresses control the speed of their skates through their smart phones. It’s an app. Something went wrong with her app, then her phone, then her skates. It was an accident, a horrible, horrible accident. The police will probably take the phone and have their techies sync it up to a computer and evaluate it.” He turned his pale-blue polo-covered back on her, and the others left to wait tables. She tapped his shoulder. He jerked around and she modeled her best solicitous smile. “There are two waiters that ran to help Nellie. One is short with dark hair and glasses, and the other is taller with green eyes and has a scar on his right cheek. Know them?”

“Of course, I do. Jamie’s the taller one, and Turk’s the shorter one.”

“Did Nellie work here full-time?”

The surfer turned toward the computer screen, “Ah-huh.”

“Did she have a boyfriend?”

“She just broke up with Jamie, the taller one. He was very upset.”

Yeah, he was; Rena remembered his reaction.

“They were going out for close to six months. She graduated to bigger, older boys,” the surfer added.

“How old was she?”

“Twenty-three.” He shook his head. “A waste of a life.”

“Yeah. Terrible. Did Turk like Nellie, I mean, as a possible girlfriend?”

“He stalked her once, but that stopped after she invited him out for coffee a few times and they became friends, and then she dated Jamie, his buddy. She was sweet, but not an easy … well, forget it.”

Yet it didn’t seem Turk cared about her untimely death. Hmm …

“Who would want to hurt her? Who didn’t like her?”

“See the people in the first booth, old, like you? The guy is part owner. The fat lady next to him, his wife, hated her because everyone loved Nellie and no one likes her. They call her Mama Cassie. She’s a bitch. Sometimes she’d go off her meds, manic-depressive, and all hell would break loose. She’d yell at everyone, but especially Nellie. But she calmed down after Nellie started flirting with Marv. Marv’s wife, Lisa, probably knows about Nellie. I think Nellie and Marv made it. Maybe the two old ladies got together and pushed her?” he said, then laughed, pressing keys on the computer.

“What’s your name?” Rena asked, agitated to hear that Marv may have had sex with Nellie, a young woman not long over twenty.

“Ian, now can I get back to work?”

“So do you work here?”

“Just when they need music. Mainly, I hang out. See ya! Bye.”

Rena glanced at Irv, talking to one of the diner waitresses, probably ordering a hamburger he shouldn’t be eating. Hmm, she pondered, who were the suspects? Jamie, Turk, Lisa, maybe even Marv, but she doubted Marv killed her. Mama Cassie? Maybe she would add Ian to the list for his charming personality. Also, who remembers how long someone dates another person? If you asked her how long she dated Irv, she’d say about a couple of years, not “almost two years” Was Ian counting? If you asked Irv, he’d look at you and say, “So, who cares about years?”

She decided to take pictures of the guests—what Marv wanted from the beginning—and dislodged the camera from its case. Eventually, the party guests settled down, and the ambulance left. The police pulled people out of the diner individually to ask questions. As they returned, they compared notes and what they had seen. Nellie’s death became the new theme of the party. Rena’s Bluetooth logo had vanished when she’d viewed the first booth through her lens. Finicky today, she thought. It had flashed a few times when she shot the diner.

Both Marv and Lisa walked through the door together an hour later, their expressions miles apart. Lisa strolled right up to Ian and whispered in his ear. Bill Haley and the Comets blasted through the diner with “Shake, Rattle, and Roll.” People peeled out of the booths and onto the dance floor.

Rena spotted Irv sitting in the very last booth with a plate of food. He waved her over.

“I’m hungry, Irv.”

“I got a shake,” Irv smiled, “chocolate. Here, steal some of my fries.”

Rena opened her computer to download the pictures from her camera while grabbing some fries, dipping them in ketchup, and savoring the taste. She reviewed the shot of Lisa seeing Marv kiss Nellie. She enlarged the picture. Ian and Turk stood on either side of her in front of the first booth, also watching the kiss. Ian’s eyebrows were raised, and Turk glowered. Lisa pursed her lips and squinted as if she couldn’t believe her eyes, but she could at the same time. The disparity of emotions in this photo could win Rena awards, she thought. She inspected the other pictures, more interested in the pandemonium after Nellie hit the car. Faces glued to the windows with old fifties high-school sweaters, wide-eyed stares, and mouths dropped aghast would have come in as second prize. Every look of horror passed through her hands in photographs, except for one—Lisa. She stood near a red-and-white fiftyish Corvette Stingray, hands folded on her chest, wearing a smirk. Although suspect, there was no proof she somehow tampered with the control of the skates. How would someone do that? If she could discover the answer to that question, she would have her killer. Right now, Mama Cassie and Turk rose to the top of her suspect list, although her gut suspected Ian or Lisa, maybe working together.

Irv’s milkshake arrived with her food. The sun moved from late morning to middle afternoon. “Eat, eat. Stop looking at those photos already.”

“We’re close to catching the killer.”

“Killer?” Irv froze in mid-sip. “I told you, Rena, not to get involved. This is not one of your police cases.”

Rena then explained everything to Irv.

“Ach, no,” he whispered as he studied the picture of Mama Cassie. “Odd she should stand that way, yes?”

“Yes, and check out Lisa and the boys, and the kiss.”

“Marv, Marv, Marv, what are you doing?” Irv yelled at the picture in exasperation. “She’s younger than your daughter, for God’s sake.” He pointed his finger at Rena. “He’s not coming to stay with us when Lisa leaves him, Rena. I tell you this right now. We’re not getting involved in their meschuggaas.”

“Okay, Irv. No one is leaving anyone at the moment.” Rena picked up her camera again. “Seems like my camera’s Bluetooth was pairing with something, on and off.”

“Pairing?” Irv asked.

“Yeah, like when my sports watch pairs with my smart phone and reads the info instantly. That’s pairing.”

“You’re too smart for me, Rena. Luckily, I can still read blueprints and build houses.”

“It’s just that after the accident, the pairing signal broke. The roller skates, Ian said, are connected to an app, and the app went haywire, and so did the skates. So … what if the skates were in pairing mode, and paired to another device, and when I was taking her picture, someone was manipulating the skates? That’s it! I’ll check the timing, pair what pictures were snapped as the Bluetooth logo lit up in my camera. Then, I’ll check to see if anyone was using their smart phone or computer at the same time. I was clicking the pictures of her skates going haywire.”

By the time her hamburger cooled and “Heartbreak Hotel” ended, Rena had her murderer, or so she thought. Now, to find the police and discuss her suspicions. “I’ll be back in a while, Irv.”

“But you didn’t eat enough,” Irv yelled to her back.

No one else had time to take pictures. The incident lasted six seconds, and the skates seemed to be flashing a light every three seconds. They were communicating with something.

Rena left the diner in search of the detective. Caution tape blocked the area and a tow truck pulled up next to the Bonneville. She spotted a middle-aged woman in a navy suit with a white shirt pulled out of her slacks. She looked like a female Clark Kent and Rena wanted to take portraits of her: sharp nose, thin lips, black-framed glasses exaggerating blue eyes.

“Excuse me, are you the detective on this case?”

“Yes, Detective Taylor, can I help you?”

“I think I can help you, but only if my theory is correct.” Rena proceeded to explain her photographic experience with the Atlantic City, NJ Police. “Can I show you my theory? I have my computer inside.”

“Sure,” Detective Taylor shrugged.

Once at the booth, Irv offered the detective French Fries. Rena slipped into the booth and the detective followed.

“Okay, here are the pictures. What do you notice about these pictures?” Rena showed the detective a slow slide show and the Bluetooth flashed with several pictures, more pronounced with the size of the computer screen. Detective Taylor squinted, then furrowed her brows, then one brow rose in questioning.

“What does this mean? The Bluetooth was connecting with the app, right?”

“But I think the Bluetooth was connecting to either of these people’s apps. The light in the camera flashes on these photos. Now these few people are using cameras, and smart phones at the same time as the light flashes.”

“Yeah, I see what you mean. Yeah. Let me check this out with my team. May I borrow the computer and the camera?”

“Sure.”

“Clever,” she said. “I’ll take it from here, but I’ll need to download all those pictures to my computer. And I need to check those skates against who may have paired them.”

She yelled to an officer to bring the skates to her.

Rena watched out the window as Detective Taylor called over one member of her team and showed him the computer pictures and the camera. She could see the Detective’s lips moving and could read some of her words. Yep, Rena thought. The detective believed her, and so did her techie.

First, the detective spoke to Ian, a contender Rena thought, but not the murderer. He watched with interest, and answered her questions nodding as he inspected the photos. Surprise and awe covered his face as she flipped through the same pictures on the computer and allowed him to check the camera.

Mama Cassie’s face turned red. Everyone could hear her scream. “I had nothing to do with that little tramp dying, but I’m glad she’s gone!” She marched back into the diner, and stared at Rena from the door.

Actually, Rena didn’t suspect her. But the detective was saving the best for last and making certain that the murderer watched the parade of suspects. Turk shrugged, and shook his head at the detective. Rena could read his lips. “I didn’t do it. I’m going to miss her.”

It was Jamie that broke down when Detective Taylor accused him of tampering with the skates through the use of the Bluetooth and the apps. Jamie cried as they brought him out for questioning, but cried for a different reason after the detective showed him the photo of him playing with his smart phone, the skates flashing a red light, which meant he previously had manipulated the skates to pair with his smart phone, the timing was exact.

“I was only trying to scare her, so I could help her, and she would see that she needed me! I didn’t know the skates could go that fast. It was an accident, a techno accident!”

The detective shook her head as she glanced over to Rena watching out the window.

The police led Jamie into the police car and left.

Detective Taylor meandered into the diner and edged into the seat with Rena. “Quickest case I ever solved.”

Irv smiled. “My wife’s a genius. Here, have a fry.”

Detective Taylor hand-picked a fry and bit into it. If you ever decide to move to LA, give me a call. I’ll place you on my team.” She eased out of the seat. “Gotta go. Thanks.”

“Welcome,” Rena answered as “Rock around the Clock” shouted over the speakers. Rena looked over her head toward Ian, who smiled and gave Rena a thumbs-up.

“Rena. Let’s go cut-the-rug,” Irv reached for her hand as he stood. “So, it was Jamie, huh?”

“Yep, said it was a techno accident. Just wanted to scare her.” Rena grabbed his hand.

“And to think we used to go to the movies for that. Let’s dance.”

END

Like what we do? Please support writers and help keep MillValleyLit ad-free. Donate at this PayPal link: PayPal.Me/yeslpk or with Venmo: perry-king-5. Subscription info here.

The Visit

by

Patricia L. Morin

We met eye to eye on my back porch. He/she/ it, whatever, didn’t look friendly. “Whatever” studied me, and I could tell by its movement around my crow’s nest, high-deck log cabin overlooking the bay, it was searching for food. I stood perfectly still.

“Looking for something?” I murmured more to myself, not wanting to scare it. As quickly as it came, it left. Maybe it’s hungry, I thought, and I should feed it?

No sooner than my mind flash on its beauty, it returned. “God, you’re fast,” I whispered as its fluttering wings zipped by me, a clicking sound following in its wake. It shone an iridescent red and green, a tiny Christmas tree of cheerful colors soaring straight up into the air like a fighter jet, but then it angled right, and returned back to the porch, wandering over the same space it just left. But then, it flew around me and stopped not two feet away from my face!

I froze.

“Lots of crow’s here, little hummingbird,” I whispered, lips barely moving. “One could snap you up and crunch you like a potato chip. If not them, those black vultures that eat live prey. Ya Hungry? Not many plants for you this year with all those fires up north. California’s burning up, little one. I can smell the smoke. I know you can, too.”

It circled me, and buzzed near my ear as it repeated its route around the porch and hovered over the gallon water jug. “It’s not sugar water. It’s water mixed with plant food for the Geraniums. Not doing well either. But I’ll buy you a feeder and hang it on the porch.” The little shining Christmas-tree clicked a verbal reply and took off.

Yeah, like it understood me. Fat Chance. I wasn’t that stupid.

I drove my ancient pickup truck down the hill to the even older hardware store on Main. I bought a plastic feeder and red sugar water. “They like the color red,” Jerry behind the counter said.

“I know Jerry,” I responded as I paid. At home, I hung the feeder up, about six feet off the ground, just like the directions read. I eyed the circling black vultures, the worst kind of vulture. Not a good year for them either.

The fires.

I waited and waited, but the sun drank the sugar water that summer. Don’t know what happened for certain to the little hummingbird. I envisioned it being chased by one clever crow knowing it would be caught by another, and its neck snapped like a potato chip. But maybe it moved on to a safer place.

Doubted it.

In a weak moment that winter, I was going to buy a little Christmas ornament I saw in the hardware store, a shining hummingbird of red and green that one could clip on a Christmas Tree, but I didn’t. I didn’t have a Christmas Tree.

I was sorry “whatever” didn’t return, but truth be told, I was mighty glad for its visit.

END

About the author:

Patricia L. Morin, MA, CSW, has four short story collections published. Her first two short-story collections, Mystery Montage and Crime Montage were released by Top Publications Ltd., Dallas TX. Her short story “Homeless” was a Derringer and Anthony Award finalist, while “Pa and the Pigeon Man” was nominated for a Pushcart. Her third and fourth short-story collections, Confetti and Deadly Illusions, were released by Tayya Press. She has written over seventy short stories and is in 13 anthologies. She is now writing her fifth short story collection: The Fear of the Number 13, and Other Psychological Mysteries. She is also a playwright.

Patricia L. Morin, MA, CSW, has four short story collections published. Her first two short-story collections, Mystery Montage and Crime Montage were released by Top Publications Ltd., Dallas TX. Her short story “Homeless” was a Derringer and Anthony Award finalist, while “Pa and the Pigeon Man” was nominated for a Pushcart. Her third and fourth short-story collections, Confetti and Deadly Illusions, were released by Tayya Press. She has written over seventy short stories and is in 13 anthologies. She is now writing her fifth short story collection: The Fear of the Number 13, and Other Psychological Mysteries. She is also a playwright.

From previous Fall 2021 Issue #19:

The Birds Will Have My Eyes

fiction by Jeb Harrison

When he finally arose on that wet, foggy July morning, his wife was already gone, leaving him alone with his old brown lab, Lou, the squawking scrub jays, the chittering chickadees, and the curious conversations of the crows over the distant rhythms of the relentless surf. If all went according to plan, it would be the last day he would hear such things, as far as he or anybody else knew.

But what ever went according to plan?

He felt good, which was all wrong. Today of all days, he thought as he brewed his morning coffee. The gnawing pain in his gut, the ringing in his ears, the eyeball twitch, the heart palpitations, the gas, the inflamed and swollen joints, the itchy scalp–the entire symphony of bodily ailments were unusually quiet, as if they were conspiring to get him to change his mind.

Hadn’t this already happened a half dozen times before in the last two years? He might’ve expected to feel uncommonly good, as he had on those other days when he had changed his mind, his resolve undermined by an irrational hope that things had to get better.

Today would be different. Today, when the pain came he would step aside and let it come, let it overtake him mind, body, soul, spirit, so that there would be no second-guessing, no questioning, no balking, no rationalizing. All he had to do was set the process in motion and wait. And if he happened to run into anybody he knew between home and his destination, he would tell them he was going to Russia. Only his most literate local acquaintances would get the Dostoevsky reference, and he couldn’t think of a single literary local acquaintance. After five years in Bolinas, he could count the names he knew on one hand, and those that he might call “friend” were exactly zero.

He was glad of the cold, swirling mists in the Monterey pines and cypress outside his window. He was glad he could hear the ocean, but could not see it, just as he was glad that the marine layer hung over the Point Reyes National Seashore like a thick rag wool sweater. The chances of anyone hiking, mountain biking or horseback riding in the dense Douglas fir and Bishop pine forest on the ridge between the coast and the Olema Valley were slim. The ridge was an arboreal carpet, thick with ferns and verdant as the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest–and even if he did see someone on the trail, he would be going cross country not long after.

As before, old Lou knew something was up. His master ignored the ball when Lou dropped it at his feet. He didn’t give him his morning treat, nor did he give him the long luscious tummy rub he was used to. Instead, his master had a cup of coffee and a breakfast bar, packed his knapsack with several items Lou was not familiar with, dressed in jeans and a flannel shirt, grabbed his hiking stick and windbreaker from the hall closet, laced up his hiking boots and walked out the front door without even giving him a goodbye behind-the-ears scratch.

He packed minimal food: a couple of protein bars and water to sustain his all-day hike, along with the fifth of J&B, the Klonopin, and a thick, hemp rope. As he approached the trailhead, he thought of the hastily scribbled note he had left behind:

The birds will have my eyes

Before you find me

He had almost left it at that, then, thinking mostly of his grown children and hoping that they might miss him, if just a little bit, he added: I’m sorry. Sure beats Brautigan’s farewell note, he thought, which had only said: “Messy, isn’t it?”

The trail was, as he had hoped, socked-in and deserted. Gossamer tendrils of swirling grey mists snaked through the heavy branches while heavy droplets fell to the damp earthen path before him. He hadn’t gone far when he realized that the old trail was nearly choked with poison oak, at times growing so high he had to push the poisonous three-leafed vines out of his way. Instantly he conjured his conditioning: I better take a hardcore lava-soap shower when I get back he thought, but then he caught himself. Even if his entire body was inflamed with poison oak, it didn’t matter. None of it mattered, anymore.

In the first mile or so, the man felt all his age-old aches and pains rise to the surface of his awareness: first he noticed the ratchet-like grinding of his arthritic hips, after which came the burning, tingling nerves in his damaged feet. Then his right eye began to twitch, and he noticed that his heart was fibrillating out of rhythm again, making him woozy. Even his nipples ached, and the tinnitus in his ears was so loud, there was no room for clear thought. I haven’t had a clear thought in years, he said to himself. I don’t know why I would expect to start thinking clearly now.

Then, as if the notion of clear thinking was in itself a form of clear thinking, the man’s physical maladies faded into the background and he was consumed with memories. Every step up the overgrown trail seemed to conjure a crippling regret, and with each regret, the memory of an egregious lie. It was the lying, or the memory of all those lies, that he now felt was fueling his inextricable march into this dense forest of no return. The physical ailments were annoying, for sure, but he could live with them.

Humans are the most adaptable creatures on the planet, he thought. If pain is my reality, then so be it. He paused on the trail, took a sip of water. But can we adapt to regret? Can we adapt to the fact that we’ve lied our way through our existence, lied not because we knew the truth, but because we didn’t know the truth?

As usual, his recollection of the various lies he’d foisted on his parents, his children, his wife, his associates, his dog; it all made him think about sin. The resulting stains on his soul–ugly, oozing black lesions filled with pus and blood, as he imagined– had blotted out the pure, white, phosphorescent goodness his soul once held. Had he been a good Catholic, he would have known that God and his sidekick Jesus forgave him, and that his sins could be washed clean with a few dozen Hail Marys, a couple of Apostle’s Creeds and several Our Fathers. But he was a lapsed Catholic, not even born of true Catholics (Dad was a Baptist and Mom a Methodist when they arrived in San Francisco, but upon finding themselves surrounded by Italians, Irish, and Latinos, they converted, if only for social reasons) and felt deep down that those born to the Anglican tradition would never be successful Catholics. Sometimes he even thought that gaining the keys to the Catholic heaven required a genetic predisposition, or at least a rudimentary understanding of Latin.

Now, his only desire was to shut it all off–the regret, the mistakes, the pain, the longing, the love, the hate–they were, after all, just thoughts. Awareness, perception, emotion; all of it nothing more than electrical impulses, firing synapses, vibrating neurons. Nothing, he presumed to have learned, could stop the thoughts: not booze, not drugs, not exercise, not meditation, not sex. Sometimes a creative exercise–playing his guitar, painting a landscape, cooking a meal–might focus his thoughts, drowning out the greek chorus of naysayers in his head. But nobody could play music, paint or cook all the time, and it was rare for any of the focused clarity of creativity to spill over into the rest of his waking life.

After several miles, the man thought he heard footfalls on the path ahead, and before he knew it, a group of elderly women in broad straw hats, each plodding along with their hiking poles, eyes on the ground. It was too late to dive into the bushes, so he simply stood aside, intending to let them silently pass.

“Oh!” the lead hiker cried when she noticed the old man standing in the brambles. “You scared us!”

The man chuckled quietly. “Sorry about that.”

The woman looked him up and down as if he were trespassing on their private hiking trail. “Do I know you?” she asked. She took off her glasses, wiped them on her sweatshirt, and, replacing them on the bridge of her bony nose, asked again: “Don’t you live in Bolinas?”

The man was caught off guard. “No,” he quickly replied. “I’m up in Point Reyes Station.”

“Oh really?” One of the women down the line piped up. “I live in Point Reyes Station, but I don’t think I’ve ever seen you there.”

“I just moved there,” the man explained, fidgeting and eager to leave.

“Where from?” the hiker from Point Reyes Station asked.

Before he knew what he was saying, he blurted out, “Saint Petersburg.”

The women stared up at him. “Saint Petersburg, Russia?”

Visions of Dostoevsky’s fictional character, Svidrigaïlov, the soft-hearted but morally reprehensible antagonist, stumbled across his nervous mind. Why did Svidrigaïlov equate going to America with blowing his brains out? Was he prescient?

“Oh no. It’s a little town up near Alturas,” the man said, hoping none of the members of the grandma hiking club had ever lived in Alturas, since there was no Saint Petersburg in Northern California.

“Oh. Never heard of it,” said the lead hiker. “By the way, if you want to get off the ridge before it gets dark, you’re going the wrong direction.”

“Thanks,” said the man. “I’m studying great horned owls. They come out at night.”

The women gave him a curious look. “Okay. Good luck!” chirped the second in line. And, hiking sticks at the ready, the women continued down the trail.

Later in the afternoon the dense fog began to dissipate and the sky lightened to a milky grey. He stopped, shed his windbreaker, took a drink from his water bottle, and, peering into a thick stand of Douglas fir and tan oak, decided to avoid any further chance meetings and leave the well-worn trail to wade into the thick undergrowth. He assumed his tracks would be undetectable in the tall sword ferns, stinging nettle, and the dead detritus from the trees above. At the same time he thought What difference does it make? The birds will have my eyes before anybody finds me. But another thought was gnawing at him. What if my wife files a missing persons report, it goes up on the text alerts, and one of those old gals says she saw me.

Quickening his pace,he soon discovered that the cross country route–what he and his friends referred to as “bush-crashing” in their young, exploratory days–was far more strenuous than he expected. After ten minutes he was gasping, bathed in sweat. He stripped down to his tee shirt, took a drink, then placed his thumb and forefinger on the carotid arteries in his neck and took his pulse. 158 beats a minute he said aloud. Jesus. And it was far from a steady rhythm. Had he been at home he might’ve popped 25mg of metoprolol to slow down the racing, the lurching, the flopping of what felt like an ocean perch dying in his chest.

He plopped down in the undergrowth, opened his backpack and quickly ate a protein bar, a bag of almonds, and a tangerine. He was tempted to take his usual after-lunch nap–the forest floor was soft, inviting and fragrant– he wasn’t worried about the brambles of poison oak that, on any other occasion, would light his thin, mottled skin on fire. But he did worry that he might fall asleep for several hours and possibly be discovered, so he decided to soldier on.

Around dusk, after several hours of clawing his way up the ridge, he finally found a fir tree on the edge of a deep ravine, The tree was perfect, hidden in a dark, dense stand with thick, low limbs–it was a tree that, in his youth, he would’ve called a “climber.” Still, he struggled. The lowest branch was about five feet up, and, while he could easily get a grip on it, he could not pull himself up. The frustrating weakness in his 72-year old arms only strengthened his resolve to climb the tree. If I can just get to that first branch, it’ll be like climbing a ladder. I just need something to stand on.

He peered into the fading light as tendrils of mist began snaking up the ravine. Nothing looked like it might make a decent stepladder, but there was a lot of dead wood nestled in the brambles. Thinking he might be able to build a rudimentary platform, he began searching for suitable logs, branches, rocks–anything he could pile up at the base of the tree that might make a good first step. Stumbling through the underbrush, he found not just one log, but a whole pile of logs, neatly cut as if by a chain saw. The ridge had not been logged for many years, but the National Seashore rangers came through every spring, sawing up tree trunks that had blown over the previous winter, but usually just the ones that blocked trails. He tried not to hypothesize on how these particular logs ended up in this dense stand of firs so far from the main trail, and instead focused on ripping them through the web of poison oak, stinging nettle and bluebush, then tossing them underhanded toward the base of the tree.

After twenty minutes of heaving and tossing, the man was exhausted. He sat down on what little remained in the pile, wiped his brow and took a drink. The fog had dropped a thick, wet, impenetrable blanket on the ridge, and he was glad of the moist air that cooled his steaming body. It wouldn’t be long before it was completely dark, though he knew there would be a full moon above that would provide some weak illumination through the clouds and fog.

As he stood up, he noticed something moving under the dead leaves on the forest floor. Poking at it with a stick, he discovered an unusually large salamander, as orange as the tangerines in his backpack, squirming for cover. My God, he thought, what a strange and wonderful creature.

He carefully scooped the slippery salamander into his palm, where, to his surprise, it seemed quite contented. Marveling at the amphibian’s brilliant orange skin, he began to imagine what life was like on the forest floor. Or under a rock in the creek at the base of the ravine.

“Are you blind?” he asked.

Then, as if the silent salamander had hired a team of spokesmen, he heard a rustling in the forest canopy, followed by a cacophonous chorus of crows: squawks, grunts, clicks, caws. Have they come for the salamander? he wondered.

He gently returned salamander to the thick undergrowth, took a deep draught of dank forest air, and walked over to his makeshift step stool at the base of the fir. Now he was a mere few feet from the bottom branch, close enough pull himself up, twist over the limb, and, using the tree trunk for balance, stand up. From there, it was as he hoped: he could step up from one branch to another, both hands firmly gripping the wide trunk, until could park himself on a fat branch about 30 feet above the forest floor, now barely visible in the dark.

Once he caught his breath, he situated his back against the trunk, legs hanging from either side of the thick, solid tree limb, stood his backpack between his thighs and began fishing through his supplies. He extracted the thick hemp rope and lashed one end around the tree. The other end of the rope was already prepared, so, like a gold medal Olympian, he draped it around his neck. Then he fished out the fifth of Scotch and the bottle of Klonopin. Down several dozen pills, chase it with firewater, pass out, fall off the branch and boom: game over, he thought.

The forest was dark, but the fog in the sky diffused the light of the full moon so that he could see, in silhouette through the canopy, the tangled limbs of the tall pines. He imagined that he had never seen the air so still and quiet.

Then he saw it.: something hanging from the broad branches of a Monterey cypress tree across the ravine was swaying against the grey sky in the stillness, as if in a gentle breeze.

What is possibly causing that branch–it has to be a branch, right? Broken off from further up the trunk and caught in the lower branches on its way to the forest floor, now hanging vertically and perhaps wishing a gust might dislodge it so it could join it’s rotting friends in the ferns below–what was making it sway like that?

Then the man noticed an odd twist, a curling, of the tip of the branch, causing him to realize that whatever was hanging from the tree across the ravine was not a branch at all. A thick hemp rope, perhaps? The remains of a tree fort?

What difference does it make anyway, the man thought. Didn’t we agree that we weren’t curious about anything anymore? Didn’t we say that curiosity will only prolong this…this…

He couldn’t say the word. Not even in his thoughts.

Right. I know. We agreed not to think that way. We’re just moving on, is all.

Slowly, almost studiously, he unscrewed the red cap of the scotch bottle and, after a slight pause, pitched the cap at the mysterious object hanging from the tree across the ravine. But it fell to the forest floor below, far short of its target.

“Shit,” he muttered, tilting his head back and pouring the searing booze down his gullet.

Perhaps it was the sound of the bottle cap clicking against the rocks and timber fall, but whatever it was in the tree across the ravine took notice. The object swaying in the non-existent breeze was not a broken branch that had been arrested on its descent to the forest floor. No. It was a tail, and it was attached to a full-grown mountain lion, a cougar, a puma. And, leaping gracefully from branch to branch, the beast landed on the forest floor with a guttural chuff that made the man’s hiccupping heart jump into his throat.

He took another swig of Scotch, then reached for Klonopin. He struggled briefly with the childproof cap, his arthritic fingers catching and popping in a hurried frenzy, until, just as he was about to pour a fistful of pills into his mouth, the cougar screamed from somewhere in the darkness below.

The man stopped in mid-pour. His hands shook violently while sweat burst from his brow as if his entire head were about to explode. He closed his eyes and tried a few deep breaths, but all he could manage were a few ragged blasts of nerves. He tried rationalizing the situation: obviously it’s not death I’m afraid of, he thought. But to be eviscerated by a mountain lion? Uh, that wasn’t part of the plan.

He could hear the mountain lion quietly slinking down the steep slope and through the underbrush in the ravine, thinking the beast must have detected his scent and was now stalking his prey. In a moment he would be able to smell the big cat’s musky odor, even though the forest floor below was enveloped in dense, foggy darkness. Then he thought of the note he had left for his wife and children:

The birds will have my eyes

Before you find me

I’m sorry.

Below, the massive, snarling cat had begun to circle his tree.

I would prefer birds, he thought, as if I had a choice in the matter. He laid his head back against the massive tree trunk, grabbed his bottle of Klonopin, and, just as he was about to pour a heaping helping of pills into his mouth, the big cat screamed.

But you do have a choice in the matter!

Unbidden, his arm jerked spasmodically, launching several pills into his mouth and the rest, along with the jar, onto the forest floor.

“Aggh!” he yelled, quickly washing down the remaining pills with a pull on the fifth, spilling scotch all over his belly. “Aggggh!” He screamed again, throwing the almost-full scotch bottle at the growling beast below. Then he unleashed a string of epithets that no mountain lion, or human being, had ever heard, a poetic epiphany of sorts.

God damn motherfucking sons of bitches

God damn your promises

God damn your heaven, your hell, your purgatory.

Then, as an afterthought, he added:

And God damn your evil child molesters

Fuck you.

The wild beast below was not discouraged by the human howls of the drunken, drugged man with the noose around his neck. But the broken bottle of Scotch at the base of the tree made such an awful stench, the cougar, knowing poison when she smelled it, became disinterested. Snarling quietly, she padded quietly through the dense underbrush, down into the ravine and on to less dangerous hunting grounds.

*****

A day later in Marin General Hospital the man could not remember the helicopter searchlights combing the Olema Ridge in the grey pre-dawn, or the rescue team that found him, still perched on his limb, in a deep, dreamless sleep against a tree trunk 30 feet above the forest floor with a noose around his neck.

The only things he could remember clearly were the lies he told the grandmas in the hiking club, the salamander, and the screams of the giant cat. And the poison oak, now manifesting itself in burning, itching, angry blisters on his matchstick arms. But he could not remember the tree-climbing, not the noose, not the scotch, not the Klonopin. But he remembered one more thing:

Why did I even think of Svidrigaïlov? Why is this idea of going to America, for 19th century Russians, mean suicide? If Dunya had loved him, accepted him, opened her heart to him, would things have worked out differently?

After a cathartic, if somewhat uncomfortable, conversation with his wife and son, he now lay alone in his hospital bed, flooded with regret.

“Dad,” his son had said, “Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem.”

A temporary problem? A temporary problem that just gets worse and worse, day after day?

“Besides,” his son continued, “I made a reservation up at Indian Creek Lodge in November, so we can fish the Trinity for steelhead.”

The man smiled and said, “Okay. It’s a date. I promise.” He hoped his son would arrange a drift boat, because his days of stumbling around on a rocky riverbed in a powerful waist-deep current were over. Or perhaps that’s how I solve this temporary problem, swirling face down in a freezing eddy.

“And I’ve made arrangements for us to spend Christmas in Sayulita,” his wife chimed in. He smiled again, slightly bemused. Sayulita had been fun in his tequila-drinking, body-surfing days. Now, the prospect of all that cancer-causing sun made him pine for a shot of Cazadores Reposado, which would most certainly trigger his palpitating heart.

“Fantastic, honey! I love Sayulita!” he cried, feigning enthusiasm.

Now, alone in his hospital room, he looked out across the Corte Madera creek to the mountain–Mount Tamalpais, the Sleeping Lady–and wondered what might have happened to the cougar and the salamander. He closed his eyes and tried to picture them; living, breathing beings, wonders of the natural world. I am not part of the natural world? he wondered, mindlessly scratching at the welts on his poisoned arms.

Those critters are out there someplace, he thought. Maybe me and my boy can track them down.

Just then, a flock of mallards descended on the wide creek, coming in low, scooting across the murky water like they were having the time of their winged lives.

What do they know that I, apparently, do not?

A hint of a satisfied smile crept across his face as he closed his eyes, picturing the trail through the prehistoric ferns, the statuesque conifers, the swirling fog, and, for a brief moment, he thought he could smell the thick forest, the dense undergrowth, all of it growing and rotting, all of it living and all of it dying, in tandem.

After a minute, he gently massaged his eyelids, just to make sure his eyes were still there, and, setting the pain, regret and despair aside, thought the birds are just going to have to wait.

END

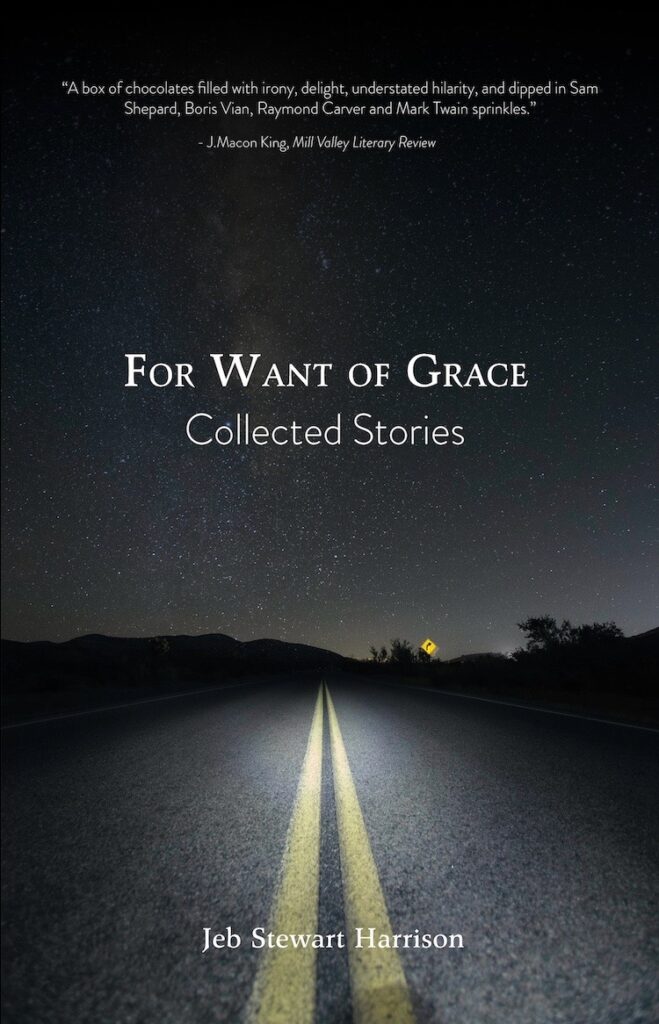

The above story is from Jeb Harrison’s new collection.

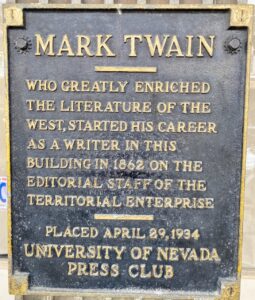

“A box of chocolates filled with irony, delight, understated hilarity, and dipped in Sam Shepard, Boris Vian, Raymond Carver and Mark Twain sprinkles.”

J.Macon King, Mill Valley Literary Review