The Power of the Magazine

In The Power of the Dog movie the callow youth finds mythic Bronco Henry’s stash of magazines depicting nearly-nude muscular men in homoerotic poses. Like many cinematists, I appreciated The Power of the Dog sets, settings, lighting, intense performances, and psychological tension. However, I find it hard to say that I enjoyed the film, or would watch again. Desire for a repeat performance is a measuring stick I’d use to judge “Best” or the size of the trophy. With twelve Oscar nominations and only one bone tossed to the dog (Best Director), the Academy obviously listened to me.

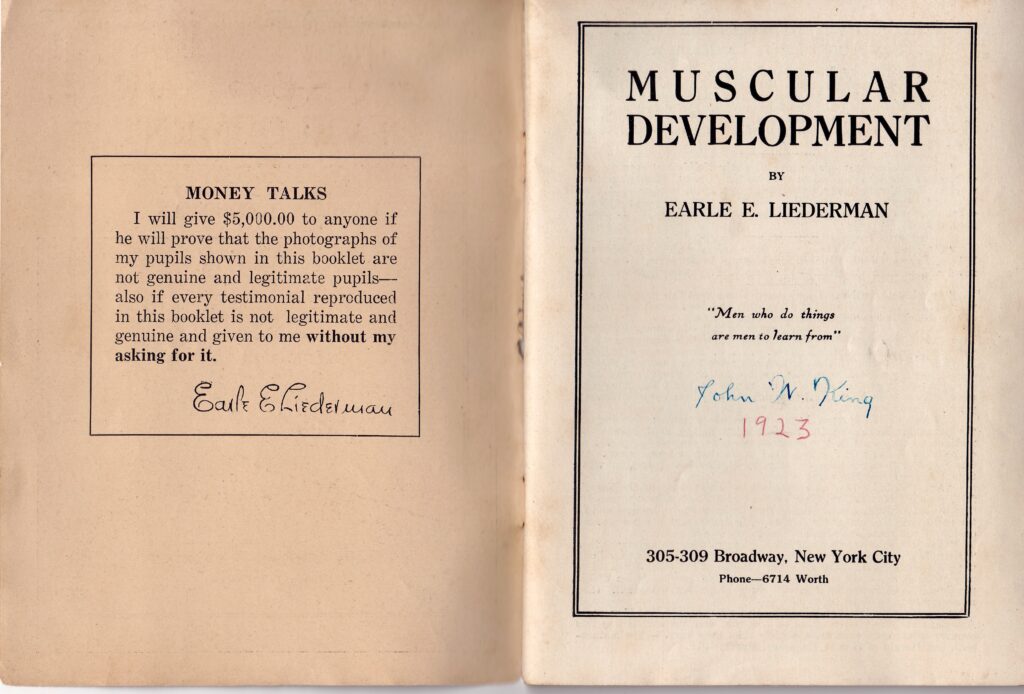

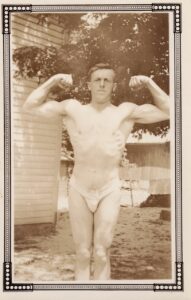

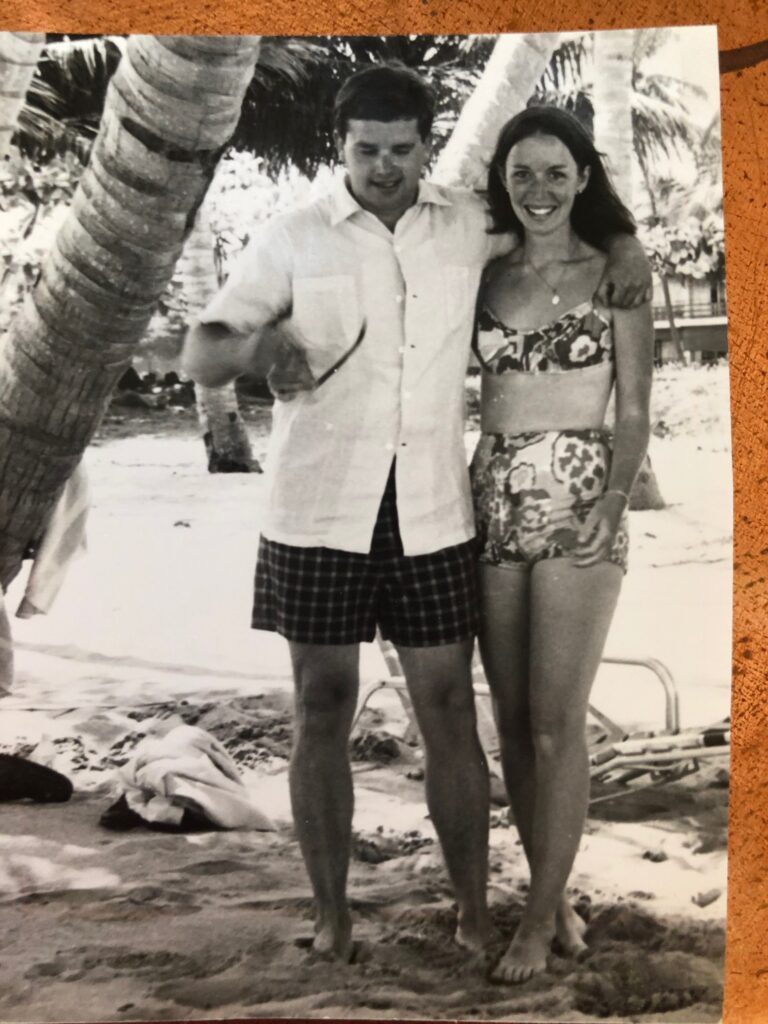

The magazine depicted here was from my my father’s prodigious stash. Dad’s stash also included “sexual medical journals” of dubious need and counsel. I found all these (in a cabinet, not in the bushes) at an age-appropriate time to appreciate such things. The magazines appeared to be popular with various people for various reasons. Dad was not a big member of a gymnasium. But he was The Collector of butterflies. (Not the John Fowles variety.)

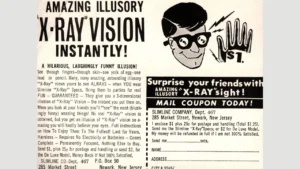

Here’s the interesting part from the inside cover:

END

Hey guys!

Careers available in the

Glamorous, High-Paying, High-Flying

{{{FIELD of POETRY}}}

“It works every time!” says U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Dee Collins.

Amaze your friend(s)!

Confound your enemies!

Learn the art of Seduction!

with Poetry Parle Parlor Tricks!

Learn:

Slight-of-tongue techniques

pedantic incongruous word usage

poetry Cheats and Hacks

Secrets of Sinonym Synonyms

Illiteration as Alliteration

Here’s how to order!

Send now for your

How to Write Poetry Good Guide

only $4.92 in U.S. postage stamps.

Not available in any stores –

Act now and we’ll throw in

a groovy free gift of your choice:

1 X-RAY Specs or 1 Sea Monkeys!

(Allow 4-6 months for delivery)

(Money-back Guarantee or Your Money Back – if available)

(Limited supply of free stuff)

Issue #20 follows:

The Literary Agent Who Lived the Plot of My Novel

memoir by Jeb Harrison

Some people say life imitates art. Other people say art imitates life.

Here’s a true story that clearly supports the “life imitates art” argument, and when it does, life can turn out stranger than the art it set out to imitate in the first place.

It goes like this: At the turn of the century I wrote the first draft of Hack, a novel which, after 12 years and several close calls had just been published by Harper Davis Publishers. In it, the protagonist fakes his own death and returns under a new identity to bilk fat sums of dough from greedy rich guys.

Hold that thought.

I signed on with my first literary agent, Melanie Mills of North Myrtle Beach, SC, on August 26 2002.

Dear Mr. Harrison:

I have reviewed your work titled “Hack” and have reached a positive evaluation of the property. I feel this property could have a great market appeal and if you choose I would like to market this book for you.

A “positive evaluation of the property”? Hallelujah! I worked on the manuscript through the winter and in the spring, we submitted and got four “good” rejections. Melanie was encouraged: all four editors agreed Hack was a riveting story with quirky characters, but the premise was too far-fetched to be believable.

Then it was Spring Break, and by chance I found an almost-free timeshare in Myrtle Beach, which in April promised family fun and a face-to-face meeting with my agent.

And so I went to meet Melanie Mills. Beyond the paved roads and onto rutted single tracks snaking between shacks on stilts crammed together, I found her: a tiny elf-like being, hunched over the deck railing of her falling-down shack. She was scraping at some old paint, a cig dangling from her lips, and a blonde wig, teased and blown into a platinum rat’s nest, resting atop her pointy little head.

We sat on her deck overlooking the slough. She talked while I noticed that it smelled more like the county dump than the salty seashore. She showed me the handful of rejection letters as she pounded back Dr. Peppers, puffed on pack after pack of Dorals, and drawled like John Wayne on Dilaudid.

She even explained that her great legs (she stood up to show me) were due to six-miles-a-day beach walks. She also mentioned that she was hosting a writers’ conference during a Harley rally in Myrtle Beach the following month, and another in the fall in Banff Lake Louise.

At her suggestion, when I got back to Fairfield County I made some broad- brush changes to the manuscript, such as making the female protagonist “less of a bitch” (Melanie’s words) and sent it back to her. Her assistant, Kat Baker told me that Melanie was traveling in Germany. I waited three weeks, and when I didn’t hear from her, I contacted her office again. I received this email in reply:

Last week, during her trip to Europe due to a death in the family, Melanie Mills had a fatal car accident. Therefore, all submission to publishers have been retracted, all events cancelled, and all existing publishing contracts have been reverted over to the individual authors. I’m very sorry. This has been, and still is, a very emotional time for her entire family and friends,

Good luck to all of you,

Kat Baker

Assistant to Melanie Mills

Never mind that she looked like Dobby with a fright wig and sounded like The Duke, I had sipped 7UP at her table in Myrtle Beach. We shared laughs. And we had talked about Hack, my story of faked death and identity fraud.

So, when I heard this news, I felt as if someone had kicked me in the crotch. I couldn’t breathe; I lost the feeling in my hands. And I bemoaned my bad luck. Now what was I going to do? My literary agent was dead!

I began scouting for a new agent. I didn’t think it would be too hard — “Hey, my agent died, would you mind reading a few chapters of the novel she was representing?”

I was right. I had many tire kickers right away, and by the following spring a new agent with a whole notebook full of new ideas for Hack. But somewhere along the line, someone suggested I look at the website “Writer Beware”. And it was here that I discovered what really happened to Melanie Mills.

She didn’t die in a car wreck in Germany. Not only did I learn that my former agent was still quite alive, but that she had roughly 15 aliases and that she was wanted for real estate fraud across the southern part of the United States, including, of course, Myrtle Beach.

She was also wanted for the attempted murder of her own mother who she pinned to a cement table with her car, crushing her pelvis.

Oddly enough, she had also published a mystery novel under the pseudonym L.R. Thomas. Her pitch letter to publishers began: “What would you do when your mother, who leads you to believe she had died, shows up months later and tries to kill you?”

Melanie Mills obviously had a thing for resurrection.

So how did she finally get caught? As it turns out, before she “died” she did organize that writers’ conference in Banff Lake Louise, that she’d mentioned when I met with her. Ironically, she did not encourage me to register, supposedly because I already had an agent (her).

The conference advertised big name authors, publishers, and agents, all drooling to make a six-figure deal. She organized and published the schedule on a dedicated website, advertised on all the sites where unpublished writers troll for agents, deployed a reservation system and started collecting money.

After defrauding writers of the fees for the conference, she took off for Germany and was killed, unrecognizably mangled in a bloody wreck. Of course, the planned conference attendees, upset though they were by her death, wanted their money back. But when the authorities went looking, they found not a trace — no bank accounts, no real estate, nothing to indicate that she had ever existed.

And in Arkansas and Myrtle Beach, where she was wanted for real estate fraud and attempted murder, more authorities started to follow her trail. With the help of Writer Beware, they made the connection between various aliases and found her. Last I heard, she has yet to be extradited to Arkansas to face attempted murder and fraud charges, and a judge had declared her unfit for trial: She’d shed her orange jumpsuit in the courtroom and was commando underneath, leading to a diagnosis of acute schizophrenia. I suppose she won’t be doing any Martha Stewart-style hard time soon.

So we’ve got life imitating art all over the place here, and yet, Melanie Mills never charged me a nickel for her services. Usually literary agent con artists charge a reading fee, an editing fee, a submission fee and then they don’t shop your book. I guess Melanie Mills was ever the anomaly, or perhaps playing legit with me was her way of thanking me for giving her the idea for her biggest con.

I will probably go to my grave wondering if Hack‘s fake death, and his return as a swingin’, Harley-ridin’, Mexican with a ponytail and pencil-thin mustache, along with his plan to rip off as many people as possible, got Melanie Mills thinking — maybe such a plot isn’t so far-fetched after all? I guess she found out.

THE END… or is it?

Read Jeb Harrison’s review of The Beatles: Get Back.

Like what we do? Please support writers and help keep MillValleyLit ad-free. Donate at this PayPal link: PayPal.Me/yeslpk or with Venmo: perry-king-5. Subscription info here.

From previous issues:

Fall 2021 Issue #20:

Tolstoy for Knudsen

memoir by Thomas Kenneth Fitzmorris

Part I

U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay, Philippines. July 23, 1976.

Aloft, the warm harbor air wafted through the rigging. The algae-and iodine-scented breeze felt almost cooling, so the tropical sun was almost but not quite completely intolerable. The waters of Subic Bay rippled 70 feet below my feet. Across the water, F-14 Tomcats thundered, pressurizing my chest from a mile away, where they hurled down the runway at Naval Air Station Cubi Point and leapt skyward all day long. Stuck on a ship, I liked the furious sound.

Twenty minutes earlier I had stood outside the bridge with my Midshipmen Training Officer, Lieutenant JK “Long John” Pierre. “Fitzmorris, you need to know the layout of the entire ship. Go aloft to learn what the Tripoli looks like from overhead. Since we’re not underway they’re doing radar maintenance and it’s danger-tagged out. Just check in with your running mate first.”

“Great. What happens if it gets energized while I am up there?”

“Well you sure would not want to stand in front of the radar antenna. The radiation would cook you and you’d be blown right off the platform. It’s a long way down. Of course, you’d be already dead so it wouldn’t matter. But a lot of paperwork for Master Chief Craig since he’s your running mate.”

Navy guys had a great sense of humor. Comedic visions of death and destruction kept the monotony from killing them.

The USS Tripoli (LPH-10) was a marine amphibious assault ship and an aircraft carrier for helicopters, hence the designation, “Landing Platform, Helicopter.” Crew of 80 officers and 638 enlisted men, and capacity for 1,700 marines, the Tripoli was 603-foot-long, fully loaded displacement of 19, 500 tons. It was a small city. To join it I had boarded a C-135 at Travis Air Force base, to Yokosuka, Japan, bivouacked for three days, then four hours on a violently loud C-130 Hercules to Okinawa where I checked aboard. We steamed under way for a week and set anchor in Subic Bay, just the night before.

Not precisely acrophobic, I have not been one to enjoy leaning out of hotel balconies. So climbing the mast was not precisely terrifying, just really intimidating. CPO Craig didn’t bother to explain exactly how to climb the mast.

“Chief Craig, do I need gloves? How about a safety harness?” I asked.

“Nope. We’re sailors. Just follow the ladders and don’t pussy-foot around,” Chief Craig replied.

Ladders led to more ladders. I pulled myself up one vaguely-greasy rung after another, slick I suppose with the fear-sweat exuded by the last midshipman to crawl up. The way to climb a 70-foot radar mast is the following:

- Never put two feet or two hands on one rung because if you do, that will be the rung that fails.

- Do not look up too much, do not look around to enjoy the increasingly impressive view, and for God’s sake NEVER LOOK DOWN. Instead stare at the tower inches in front of your nose. It is steel, it is solid, and it is your constant companion.

- As you climb meditate on God’s everlasting love for you as he holds and protects you within his bosom.

Reached the first radar 50 feet up, “Fuuuck,” I sighed in relief. A plastic milk crate took up half the footprint of the crow’s nest. In it were a grease gun, a gallon of # 5 Standard Navy Gray and curiously, perched on the paint can, a tattered copy of Tom Wolfe’s, Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Apparently someone came up to read.

“Good work, Fitzmorris.” Chief Craig was keeping an eye on me. He called up from below, “Of course, you could stop there like a pussy, or climb the rest of the fuckin’ way up. Hell, the last middie we sent up was already at the top by now.” This was all said in the typical Navy Tone, serious but good-natured and without malice. What Chief Craig actually meant: “Get-your-ass-up-there, college boy.”

Skyward I climbed in response, stepped onto the top crow’s nest and leaned against the mast. Wine-dark waters below brightened to teal in the outer harbor. Beyond the harbor the wind frosted the navy-blue ocean with white caps. I ignored the brooding thunderheads slouching against the horizon, loitering with their hands in their pockets. Below me lay the point of the spear of America’s military-industrial complex. Vast Subic Bay Naval Base, at 262 square miles was the size of Singapore. Dockside, the aircraft carrier USS Kennedy and a dozen other warships were tied up. Numerous combat and supply ships lay at anchor or were putting out to sea. Behind me, Cubi Point NAS and its thundering F-14’s dominated my eyes and ears. Fighter squadrons VF-1 and VF-2 had been flying the Tomcat less than two years; pilots were ecstatic to leave the F-4 Phantom behind. Designed as an air superiority fighter, its climb rate of a frightening 30,000 feet/minute, and top speed of 1,544 mph, was without equal. I felt a tingly pride, but my impending descent made contingent my joy.

The blazing sunshine urged me down. Being with the 7th Fleet was an eye opener, but so was the weather. It was Monsoon season. So, slightly lower temperatures but oppressively humid. As a California kid I had never experienced heat on top of humidity so heavy that you had to push your way through it. And the rain. Visiting the old Fort Santiago in Manila I walked from one guard tower to the next. It started to rain. Running for cover over less than 50 feet I was completely drenched. So, “raining in buckets” is real.

I descended, focused on the mast inches from my nose, freshly painted with # 5 Standard Navy Gray. The acetone that wafted off the paint buzzed me like a gin and tonic, while my feet felt their way down on their own. The breeze freshened as those clouds, which in retrospect had not been loitering, raced toward us, painting whitecaps onto the darkening harbor.

I was midway between the two crow’s nests when the squall struck. Vast sheets of rain slammed onto the harbor around me, churning the surface like sardines leaping from marauding blackfin tuna. My inner rabbit emerged from my amygdala and we froze in terror, hoping I suppose that the squall wouldn’t notice me. Instead 9 mm raindrops pelted me from the side, so I wrapped my arms around the rungs. Then felt my way 10-feet down to the first crow’s nest in time to watch the wind levitate The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test above the can of # 5 Standard Navy Gray, then blow it right off the ship. The mast started to move. Not much, but one degree of ship’s roll at 60 feet is 1 foot of sideways motion. The rabbit came out again at two feet of sway. Then, as suddenly as it appeared, the squall wandered off to harass something else. The sun baked the rain away in seconds. Squalls come and go quickly, and Tripoli got a glancing blow. Relieved, I climbed down without stopping. Chief Craig only said, “Well, you’ll remember that climb. Good job.”

We Midshipmen were expected to learn not only our ship’s operation but also the traditions, the culture, the Navy Way. I learned three things:

- Anything that moves is noisy.

- Everyone smokes every chance they get.

- Nobody can say a single fucking sentence without using the word “f*ck” for every fucking part of speech. I mean fuck, everything.

A week later my rotations put me in the engine room, then the boiler room. Even at rest in the harbor the steam plant had to be powered, and the boiler fired up making steam. This city ran on steam. The engine room was 100 degrees and not a dry heat. Sweat poured constantly, soaking my tropical-weight Navy khaki uniform. Did I mention loud? No one wore earphones or headsets. They just shouted. The boiler room, incredibly, was worse. I never knew but guess that decibel levels were perhaps 100 – 110 dB, like a Led Zeppelin concert from the front section. It was so loud that I discovered by pressing my ears closed I could understand what the chief was saying. Apparently, his sound traveled through my neck and head, better than through the air. No one seemed to be aware of the dangers of hearing loss, which I have today. One year later, at my next job, operating a giant machine was a cakewalk even for a city-boy like me.

I jumped a ride on a Marine UH-1 “Huey” helicopter to Manila. Looking back, flying over those rice paddies was something right out of Apocalypse Now, without the napalm. It was deafening with the doors open. Headsets were helpful. Some Navy pilots I met had a constant look of relief behind their eyes. Invariably they had been flying in the war.

Mad-Mike, our Huey pilot yelled over the roar, “Tell you what Fitzmorris, you are fuckin’ lucky to be born when you did. A lot of my buddies never made it out of ‘nam. Three years ago I was dodging fuckin’ gook gunfire and rockets. Two years ago, Jackson here replaced my co-pilot in time for ‘Operation Frequent Wind’, airlifting fuckin’ Vietnamese officers and their mistresses out of fuckin’ Saigon. Peacetime is fuckin’ great.”

“What happened to the other co-pilot? Finish his tour?” I asked.

“Hit in the throat by 14 mm round from a fuckin’ ZPU-4.”

Two weeks later, August 19, 1976.

“Fitzmorris, there has been an incident in North Korea, and we are waiting for orders,” said Lt. JK Pierre. “Two army officers were murdered yesterday with axes at the DMZ. Midshipman on board the USS Kennedy off the Korean coast have been flown off because WestPac Fleet has gone to DEFCON 3.”

“What does this mean for me?” I asked.

“All leave is cancelled for all personnel and midshipmen are to stay aboard ship.”

The next few days were hectic in the West Pacific as nuclear-loaded B-52’s circled Korean airspace. War was avoided and the Subic Bay returned to post-Vietnam normalcy. My tour wound up. “Fitzmorris, you did well, finished your cruise manual, but I wonder if you had your heart in it. Are you going to stay in?” said Lt. Pierre.

I reflected on the interesting people, the impressive engineering, the hazards, the boredom and the noise. Then there were the eyelid-lifting libertine liberty calls. The Sirens of Anthemoessa had nothing on the bar maids of Olongapo City. Vietnam was over but the Navy still partied like it was 1972. “It’s been a great experience. I guess I have some thinking to do,” I replied, although I already knew.

I embarked from Clark Air Force base bound for Travis via Anchorage. The familiar Sitka Spruce and Alder trees outside the terminal windows gave me a shiver of gladness. Landing at Travis Air Force Base I walked down the stairs to the tarmac with beautiful California sunshine blowing arid air through my hair. I wanted to kiss the ground. Instead I walked to the terminal and caught my flight home to Los Angeles.

Part II

Rehrig Pacific Company, Vernon, California. June 16, 1977.

Ten months prior, as we almost went to war with North Korea, being in the Navy’s 7th fleet in the West Pacific, was cool. But the prospect of 7 years of boredom was not. Before Christmas 1976, I asked to be released. My ROTC Class Officer, a bad-ass Marine Lt. Colonel Jacque Pays D’abord, wouldn’t let me. The Navy had too many history majors to fill billets in Nuclear Engineering; I studied physics. “Fitzmorris, I will agree to a leave of absence. Then decide this spring.”

But by Spring I made it final and needed a job.

Vernon is a town with no residents. Its citizens are companies. Five miles south of downtown Los Angeles and 5.2 square miles, it‘s an industrial area that the west coast Farmer John packing plant still enjoys calling home. With its Philadelphia sibling, Rehrig produces 85% of the cases that shippers use to transport and store milk and other liquid containers. Many have ended their lives on the back of motorcycles or in college bookshelves. Rehrig has operated at 4010 East 26th St. for decades. My twin brother Jerry and I showed up for the summer of 1977 with the confidence of all tall college athletes. Not on scholarship, we showed up because we were broke.

Being the Engineering Student, Jerry got the engineering intern job, $4.50/hour working directly for Bob, our supervisor. Being a Physics Student, I worked the presses, $3.10/hour. But hey minimum wage was $2.30/hour. Each 10-ton Cincinnati-Milacron injection molding machine was as big and heavy as a small locomotive. The building held twenty of these dragons, storage warehouse, shipping and receiving facilities and administrative offices. The molding machine galley had no air conditioning. Summertime in central L.A.: it was hot and loud. Felt like I was back in the Tripoli’s boiler room.

This is what the machine operator did: Close the door panel. Push start. The two sides of that mold would come crashing together, like a freight train. The power, speed, and noise where startling. Plastic pellets were fed into the extruder. The extruder exerted ten tons of pressure onto the plastic, liquifying it so that it fed into a mold which was a negative of a milk case.

The machine had one safety feature; a switch on the sliding door prevented the mold from cycling with the door open so the mold would not spontaneously ram close, clamp down on your arm and make a milk crate out of it.

The entire injection molding cycle took about one minute, only 15 seconds during which the operator was busy running the case through the hot-stamper to stamp “Knudsen” or whatever onto it. I quickly got bored watching nothing happen, so I brought in some reading. I opened my book and propped it on top of the operator’s console. Our boss had never seen this before from the Hispanic workers who were my brethren machine operators.

“What are you doing with a book on your console?”

“Reading.”

“Seems like a distraction, which makes it a Safety Hazard,” Bob thrusted.

“Keeps me from being bored and drowsy, which are Safety Risks,” I parried.

“Fair point. Whatcha reading?”

“For now, War and Peace. A really a great yarn as well as a great piece of literature. Part of the opus, the western canon.”

Bob, who had received his engineering degree from a reputable school in Manila, was uncertain whether I was giving him college-boy horseshit. He pivoted, “How far can you get in one cycle?”

“A paragraph at least. You know, Tolstoy could write quite a paragraph so it’s entertaining at two levels- great story and competitive reading,” I said, trying to look unsmug.

“Just don’t let the plant manager see you. I’ll deny I knew about it.” Sword sheathed, Bob sauntered off.

Bob couldn’t think of any reason why I should not do this, so he let me be. After all, I showed up for work every day, had all my fingers, and spoke English as a first language.

After working 16 days straight, we managed to get the fourth of July off. Jerry and I went to our friends Sally and Dick Beamish’s party (also twins). A little 250 cc Yamaha motorcycle in the driveway looked like fun so I borrowed it. It becomes significant that although I wore a helmet, I wore no protective clothing. A cooling ocean breeze blowing onshore flowed over my bare arms and legs raising tingly goose bumps as I purred along Sunset Boulevard then down into the Eucalyptus-shaded canyon on West Channel Road, and finally cross over to Santa Monica. The traffic was light, and the shifting wasn’t hard to figure out. Joy bubbled laughter out of me.

At the top of the canyon West Chanel Road meets San Vicente Boulevard. When the light turned green, I put the bike in gear to turn left. It so happens that a bike does not turn like a car simply because you turn the handlebars. The accelerating bike zipped enthusiastically across the intersection yet only half-heartedly curved somewhat leftward. Bang! Up the curb, grazing the traffic signal pole, scraping me onto it before falling on its side, stopped, wheels still spinning. Cracked helmet, and my right ribs hurt so I could hardly breathe. Lying in front of me the milk crate was still bungeed to the back of the bike. Big white stamped letters said, “Knudsen” and a small imprint said, “Rehrig Pacific”; fuck, I mighta made that case. I wondered if it was an omen. I staggered to the corner house and they let me call Jer at the Beamish party.

“Where are you?”

“I crashed. I think I need to go to the hospital. But don’t tell Mom and Dad.”

“What about the motorcycle? How did it happen?” Males always ask what happened while females ask if you are all right.

“Motorcycle seems OK. Just pick me up.”

Jerry and Dick showed up 15 minutes later. Dick rode the motorcycle back and we drove home, since I couldn’t go to the hospital without the parental’s knowledge.

“It hurts to breathe. Maybe I’m dying.” I offered, looking for sympathy to paper over the distain from Jerry for being so unmanly to crash a little motorbike.

“My friend Mark fell on a guy during a league basketball game. Hurt like hell and he could hardly breathe. Turns out it was a cracked rib. You probably have that.”

We tooled down Sunset Boulevard through the Pacific Palisades village. Our 1965 dark green Mustang we called the Toad, four on the floor with a 289 V-8, was not overpowered but could move right along. We couldn’t afford anything like tires so in retrospect what happened next was not surprising. Driving downhill and zipping around the Self Realization Fellowship Shrine, the Toad spontaneously pirouetted 90 degrees to the left. Astonished, we looked at each other thinking the same thing: Which way do you turn the wheel?

“Turn left?!” I offered. We were 75 feet farther down the road, sideways.

“Turn right?” Jer pondered. Another 50 feet.

Neither of us remembers what way Jerry turned but probably it was the wrong way, or perhaps it didn’t matter. Suddenly we were sliding backwards down Sunset Boulevard at 45 mph into oncoming traffic. Miraculously the few oncoming cars poured around us until we slowed enough to whip a uey back onto the southbound side of Sunset. This adventure turned out to be helpful. We had a good story to tell Dad instead of what had happened on my (last-ever) motorcycle ride.

While I operated hot, loud, dangerous equipment, Jerry, the Engineering Intern, performed Quality Control, counted enormous stacks of crates, and generally got to fuck around and do whatever he wanted to do. One fine day Jerry walked down the galley past one press after another and stopped at my machine.

“Tom, I’ve been in the warehouse all morning and it’s so chilly I thought I’d come here to warm up.” Jerry shouted at me after my press rammed shut, interrupting my Tolstoy.

“Fuck you, Jer, Mr. Clipboard.” I yelled over the din without malice.

Jer, bent over, laughing. A citreous puddle of oil on the floor interrupted his gaze. Hmm, curious. And a Safety Hazard. Jerry looked around to see where the oil may have come from. No suspicious oily boot prints leading to a careless worker. No leaking containers. In fact, no obvious source.

“Plip.” A drop of oil landed in the puddle sending little ripples outward. Hmm. Odd.

“Plip.” Another drop.

The drops sent out nice little concentric circles like a stone dropped onto a pond instead of skipped across it. The 200-foot long concrete-floored galley had 30-foot ceilings with vertiginous industrial skylights far above. Jerry, being an Engineering Guy, knew that, as improbable as it was, the oil must be falling from above. He looked up. The skylight 30 feet above his head had a strange black circle, as if someone had spray-painted graffiti on a transom window. Wonder of wonders.

Jerry wisely found Bob. They approached the puddle. “Jerry, don’t move. Tom, step way back from your press.” Bob took a piece of paper from his notebook, stepped over to my 10-ton press and passed it over the one-inch hydraulic hose that powered the beast. The paper sliced neatly in two. A fine invisible stream of oil from the 3,000-psi hydraulic hose was shooting up 30 feet onto the skylight and then dripping down. “That would take your arm off.”

I was impressed but not shocked. In the Tripoli’s boiler room, the year before, Chief Craig had shouted through the din, “Last month a seaman apprentice heard a hiss and reached behind the steam lines with a fuckin’ wrench to find the goddamn leak. Live steam is a gas and you can’t fuckin’ see it. That pressure becomes fucking high velocity in a leak.”

“What happened to the sailor?” I had asked.

“Steam hit the wrench so hard it fuckin’ broke two fingers, almost took his eye out too. He was lucky, guys have lost their arms. Funny, he used to go aloft and read, some fuckin’ book about Kool-Aid and electricity. He ain’t doing that anymore.”

The other job for the machine operator was to run the hot stamper. A customer like Knudsen Dairy would order 1,000 cases and each case would get labels hot-stamped onto it. This is how that happened. The operator pulls the hot case out of the Dragon, takes two steps to the right, slides the case onto a horizontal steel plate. Checks that the plastic roll tape is in position, then with left and right hands simultaneously presses the buttons on the two handles, known as a dead-man switch. The press would only stamp when two hands pressed the two buttons. The upper stamp plate, heated to 350 degrees, presses the tape with five tons of pressure, melting it into the case, permanently Marking It for Knudsen. The tape would stick as it cooled. So, operators would lift any sticking tape off the case with a sawed-off broomstick, then added the case to the growing stack for delivery to the warehouse.

August 18, 1977. Day after the hydraulic hose leak. We arrived at 7:20 a.m. to find Bob sorting out commotion at the hot stamper line.

“Jerry, here is why I told you to never let the operators over-ride the dead-man switches. You know how these night shift guys try to tie down one of the dead-man buttons?”

“Yea, so one hand operates the press, the other hand is free to run the stick under the tape. Faster so less sticking,” Jer said.

“Well Jorge not only taped closed one of the buttons, but also used his hand instead of the broomstick. Must’a’ pressed that button at the wrong time. Anyway, the press stamped while his fingers were in the way.”

Two fingers were still lying on the ground, breakfast sausages. Maybe it was a crime scene, so they didn’t want to disturb anything. It sure disturbed me.

Lunch. We walked to the taco truck, which was a bit like walking over to Mexico—hot, sunny, concrete buildings and friendly muchachos. Naturally no one spoke English.

“Hola, Tomas. Hola Mister Boss.” Normally there would be grinning teeth and laughing eyes everywhere. They always called me “Tomas.” And Jer they called “Mr. Boss.” Funny they didn’t call him Senior Boss, like in the movies. Mister Boss. Today more workers than usual had gathered. The Guatemalans in their straw hats were queued at the truck as usual. The Mexicans stood in a circle in their cowboy hats, all talking at once. In the middle, stood Jorge, the guy from the accident. We knew this because he waved his hand at us, bandaged with two fingers missing.

“Hola Mister Boss, ¿Puedo trabajar en el almacén?” (Can I work in the warehouse?) “No puedo hacer funcionar la máquina ahora, no tengo suficientes dedos.” He waved his two-fingered hand at Jer.

“Jorge, I’ll will ask my boss, Mister Bob.”

Jorge’s teeth were smiling but not his eyes. I give him one thing, he was tough.

On the drive home that evening, The Toad felt like our get-away car as it rumbled down the Santa Monica Freeway. In our moody silence, my eyes wandered to the two-inch gap between Toad’s bootless-gear-shift and the transmission tunnel and then on to watch the freeway flow by.

“Jer, what the hell are we doing here anyway? Feels like being swept through rapids without a boat.”

“I dunno.” Jerry paused. “Calmer waters ahead and I bet someday we’ll be glad we learned what it’s like to sweat for a living.”

“And we got stories to tell our kids and grandkids.”

We glanced at each other, laughed, and resumed our silence as the freeway flowed around us, two rocks in the river.

Safety rules were reinforced, and thankfully, no one lost their arm, or eye, or more fingers that summer. Production demand sagged so Jerry lost his cushy supervisor/QA job and had to work on the Dragon Monster like me. Jorge was given $500 and a bus ticket to Guadalajara. I soldiered on for the last month. Like Pierre watching the carnage of the Battle of Borodino in Book Three of War and Peace, I remained horrified by the errant fingers. Yet managed to finish the summer intact while I read Tolstoy for Knudsen.

END

Postscript

Jerry, degreed in Chemical Engineering, worked for a year as a process engineer, and then walked into the Pasadena Navy Recruiting office. First, Officer Candidate School Newport, RI, next Nuclear classroom training, Orlando, FL, and finally Nuclear reactor training, Ballston Spa, NY. After training he completed one tour of duty in the West Pacific (and we’ll never know where else) on the USS Pollack, a fast-attack nuclear submarine on which they did shit that to this day remains unclassifiable. Then trained and qualified as the US Navy’s 440th ever Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle (DSRV) dive pilot.

I got my Physics degree and worked on cool Star Wars stuff at Lockheed Research: By the age of 24, I had helped build a prototype laser system that hit moving targets the size of an orange from 3,000 miles, and a battle-tank gunsight protection via ultra-fast spectrum-scanning optics so fast it detected incoming lasers and blocked battle-field enemy laser beams before the operator could be blinded. Also married my sweetheart and started having kids. The Navy would have been a good move but not the only one.

About the author:

Thomas Kenneth Fitzmorris stepped into writing with Stanford’s Creative Writing program in the Fall of 2019. His second class was a workshop for which he wrote, Down to Peru. The memoir was awarded second prize in Blue Institute’s writing contest, prose category. A father of four, grandfather of five, his other passion is surfing. Beyond the California coast (Santa Cruz!), Tom has surfed Bali, Australia, Hawaii, and in several Latin American countries.

#

From previous Issue #18:

“(Sam Shepard) drew another audience through his movies, and that was outstanding. He was a very handsome, popular young man. It was a form of mass hypnosis. He played Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff, the man who broke the sound barrier, and people literally thought Sam broke the sound barrier.” (See story following current piece here.)

“Sam Shepard remembered by Johnny Dark” Obituary 2017 in The Guardian.

From Spring 2020 #16:

Follow the Devil to the Deep Blue Sea

by Christie Nelson, excerpted from her memoir “The Biggest Gamble of My Short Life”

“Zander, you bastard,” Drew shouted into the phone from the kitchen. “How in the hell are you?”

I shifted my weight and balanced The Brothers Karamazov against my belly that barely revealed any sign of pregnancy. Ah, Zander, the devil’s playmate. Did I hear a thunderbolt rip across the sky, or was it just a car backfiring on the street?

“No kidding,” Drew said. “Those were good times.” He paused. “No shit. Really?”

I could hear Drew opening the refrigerator and then closing it. Water ran in the sink. A rhythmic tapping sounded against the linoleum, the slap of his bare feet. The air was filled with the feeling of inevitability.

“Well, I appreciate that,” he replied. “Did you know Chrissy is pregnant? Yeah, a big surprise. We found out after we got back from Amsterdam. The baby’s due in October. How’s your kid?”

Another silence. When Drew spoke again, his voice was louder. “Let me talk it over with her. The main thing is don’t let us hold you up. I’ll get back to you. Say hello to Frannie.”

He wandered back and behind his horn-rimmed glasses, his eyes glittered. I could feel the hand of fate brush against my cheek.

“Let me guess,” I said. “Zander’s bought a new boat and he wants us to join him.”

“He and Frannie are down in Miami. They found a double-masted schooner. They’re ready to sign the papers.”

I rolled onto my side and propped a pillow under my head. “What’s to prevent this boat from blowing up?”

“That kind of shit only happens once.”

“I’d say we were lucky.”

“Admittedly, we shouldn’t have been on the Atlantic in November,” he said.

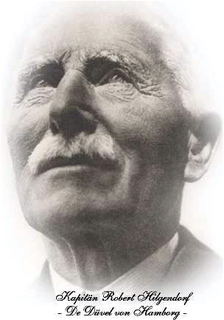

No, we shouldn’t have, I thought. My mind wandered backwards five months to the frigid morning when Zander’s boat was tied up to a dock in Portland, Maine. The tide was out, and the dock that reeked of creosote hovered eight feet above our heads. In truth the boat wasn’t yet a boat; it was a monster hull—117 feet long and built like a Gloucester dory; long, tall and narrow, a square-rigger in the making. Powered by a ’56 Chevy V8, rough planks formed the deck. The hull was ballasted with hardened steel shafts reclaimed from a closed New England textile mill, and buried in the bilge under concrete. Zander had named the ship Hilgendorf, in honor of a legendary German sea captain known as “The Devil of Hamburg.”

Master of 66 sailing trips around Cape Horn.

Sailors believed he could control the winds with black magic.

We had been motoring from Northeast Harbor down the Maine coast heading for Miami with a small crew of friends. Once there, the ship was to be fitted with masts, rigging, and sails, and we were going to begin a trip around the world.

The miserable grey morning when the boat blew up was so bone-chilling I could see the breath of my shipmates turn cloudy around their faces. We had been trying to keep warm and stay busy with chores. A refueling tug bumped against the side of hull, pumping gas into the fuel tank in the bow. Suddenly an explosion ripped through the air. A static spark had ignited the gasoline and blew a hole as big as a truck through the deck.

I remembered Drew yelling my name. I was below deck. His hand reached through the rear hatch as he hauled me up into an inferno. Flames licked high across the decking from stem to stern. Smoke and fumes swirled in sickening waves. “Jump on the tug!” Zander yelled. Around me our shipmates were hurling themselves overboard. The distance between the tug and the boat was farther than I had ever jumped. Zander leapt first, landing on the tug. Below, seawater lapped against the sides of the hull. Frannie and Drew leapt in turn, each spanning the breach. Gripped by panic, I willed myself to jump. I hit the railing and felt arms yanking me up onto the tug. Zander pulled a bowie knife from the sheath on his belt and slashed the gas line. He shoved the dazed skipper aside, took the controls, and sped away across the harbor.

In a thick mist, dazed and in shock, we watched the ghost ship burn. The Portland Fire Department blew foam onto the flames and chopped holes in the deck. The Red Cross put us up for the night. The next day, November 22, 1963, at a bar on the docks, we waited to hear how much scrap dealers would give Zander for the metal in the charred remains. The news that would signal the end of Camelot flashed on TV: John F. Kennedy, our beloved President, had been shot by an assassin and pronounced dead in Dallas.

Back in our studio apartment, recalling those events, I shivered at the memory. “I’ve never been so cold,” I told Drew.

“You wouldn’t be cold in the Caribbean,” Drew answered.

“Can we be lucky twice?”

“Look at me. Am I lucky or what?” he asked. “I’m like a god-damned cat.”

I couldn’t argue.Drew had been thrown out of a prestigious ivy-covered college after his father found him drunk in a snowbank. There had also been the matter of cutting his wrists his senior year of prep school. This improbable act of desperation seemed at odds with his bigger-than-life personality. He was committed into a “nut house,” as he sarcastically called it. “When I realized the docs were serious about keeping me in,” he told me, “I figured out how to play their game and get out.” He headed West. Fueled by Kerouac and the Beats, he landed a stint at lumberjacking in the Oregon forest for a summer, and then hitchhiked down the coast to San Francisco.

“Okay,” I said, pushing him away. “Tell me about the new boat.”

“They’re taking it down to Nassau. Zander said we deserve a trip.”

“The plan is to sail to Jamaica through the Windward Passage. Zander’s papa has a spice plantation in the hills above Ocho Rios. Horses and all that kind of shit.”

I rolled onto my back and gazed up to the ceiling. I knew my days in the apartment were numbered. I had promised myself to never set foot on a boat again. But I could already hear the snap of the wind in the sails and smell the sea.

***

Meeting Zander and Frannie was an innocent twist of fate brought on by a phone call from a schoolmate of Drew’s when we were visiting his parents in Greenwich, Connecticut. “There’s someone I want you to meet,” the friend said. “The guy and his wife are building a square rigger in their backyard. I’m going over tomorrow night. You interested?”

On the drive over, we heard about Zander and Frannie. “She’s a trust-fund baby of a wealthy Philadelphia family,” Drew’s old buddy told him. “Zander’s the black sheep of the founder of one of America’s biggest financial institutions. His family endows libraries and museums. Each quarter the bank wires him a check bigger than what I make in a year. Let me warn you, though. He’s been in and out of Menninger’s more than once.”

“Just my kind of man,” Drew laughed. “We’ll get along fine.”

I listened, fascinated. His remark sounded like confinement in a mental institution was the same as membership in an exclusive country club. My world was spinning faster than I could have imagined.

The house Zander and Frannie had rented was a rambling mansion with a backyard that extended to a dark wood. The hull of the ship, constructed of steel and lumber, was held upright inside a wooden crib. We picked our way across the driveway, stepping over tools and around debris to find the front door.

Inside the house, blueprints, charts, and sheet music was strewn over the furniture and on the floor. White rabbits skittered in and out of a cardboard box stationed in a corner of the dining room. In a frenzy, Zander pounded the keys of a baby grand piano. A wild-haired Beethoven in rumpled jeans and a flannel shirt, his piercing black eyes acknowledged our arrival. Frannie was a blonde waif in need of a hairbrush and a dental appointment. She didn’t take her eyes off Zander, who went on a rant telling us about the boat, the Hilgendorf, and how they intended to take it to Maine, and then sail around the world. When we said good-bye, I was sure I’d never see them again.

***

Ours was a blue-eyed boy. When our son was three months old, we flew from San Francisco to Miami and hopped a flight to the Bahamas. At Nassau Harbor, I squinted down the dock. The schooner’s masts rose high above the other yachts. It was, as Zander had promised, a fine ship. Off we sailed–two certifiable inmates, one woman who could navigate by the stars, a woman who hadn’t passed the Red Cross safety swimming test, one infant, our son, and one child, just a year old, Zander and Frannie’s son.

For the next month, we sailed through the Windward Passage like vagabonds, going ashore at nameless islands, fishing, swimming and diving. Before we left the Bahamas, Zander gave one of his lectures, his hands flying to his hair as if he could pull it out by the roots.

“Getting to Jamaica from here is a long haul. We won’t see land until we get there. It could take a week if the winds are high, or two weeks if the winds die. When the winds stop, we stop. At no time do we run the motor. We’re sailors, not god damn mechanics.”

Our course was due southwest heading between the eastern tip of Cuba and the western fist of Haiti. I imagined the guns of Guantanamo aimed at our prow. On the third day in open seas, past any threat from Castro, the skies clouded over and the barometer dropped. The wind had a nasty whine to it.

We huddled in the cockpit, Zander at the helm. The barometer kept plunging. Rain began to spit from the sky. The wind picked up speed. My nervous system radioed danger, shooting electrical currents through my arms.

“We’re sailing into a mother of a storm!” Zander yelled above the wind. His black eyebrows furrowed into a continuous scowl. “Frannie, take Chrissy below. Strap down the kids and store every goddamn thing you see. He tipped his chin toward the darkening sky. “Have at us, you bastard. We’ll take what you’ve got.”

The wind howled and shrieked. The boat was like a pendulum. It rose on a wave, hesitated, and slammed violently over to one side. I braced myself in a doorway and stopped breathing until the boat righted. The sensation was a series of sickening freefalls in which there was no up and no down, only inevitable impact and collision. Once again the boat began another slide down the trough of the next wave before it was broadsided again. The grinding squeal of the boat’s ribs was deafening. The adrenalin in my body pumped so hard that all nausea vanished in an instant.

Frannie and I struggled toward the hatch. Rain dumped from sinister clouds. Cold and lashing, it came down in sheets. We pitched down the stairs into the main cabin, losing our footing as the boat crashed into a wave.

I tucked pillows around and over our son and against his head, leaving a little air space for breathing. I ripped sheets into strips and lashed his body tight to the bunk. I removed anything that could fly off the walls or floor and strike him. He was quiet as a lamb, his eyes closed, his body compliant. I knew if I climbed into the bunk to hold him, the force of a wave hitting the boat could send me on top of him and I could smother him in an instant.

Frannie shouted that she was going back on deck. She grunted against the hatch. I felt the wind’s blast as seawater streamed down the stairs and splashed into the main cabin. Then she was gone.

***

I cringe to remember that night. There were years when the demands of everyday life as a parent required all my energy and fortitude, and the memory of that night lay dormant in the recesses of my mind. We told ourselves that the only life worth living was the one where death was a possibility. What did we know of death? Of risk? Of responsibility? We thought we were invincible, but we were fools who were spared disaster only by providence. And so, the biggest gamble of my short life became my biggest folly. It would be an index of recklessness against which I would measure other choices, though none so mad as to board a ship with my three-month-old infant and sail onto the open seas.

And what of the others on that ship of fools?

Long after our adventure, Zander ended his life by his own hand on an island in Maine. The devils that hounded him finally found their mark. Frannie survived to settle on a horse farm in Connecticut. Drew rode away on his own star—far and wide. Our marriage was one that could not last.

And me? When I bolt awake in the middle of the night, my body soaked in perspiration, my heart is racing. You’ve been dreaming again, I tell myself. In the dream my son is drowning and I’m trying to find his precious little body in the waves. I wait for my heart to slow, and settle back onto the bed. Thank God, I tremble. What was I thinking? How could I have been so reckless? Now in the hours before dawn when the silence is deep and the air cold as a coffin, I am the one left to join the uninvited ghosts. I am the one left to remember.

END

Note: in this memoir some names have been changed.

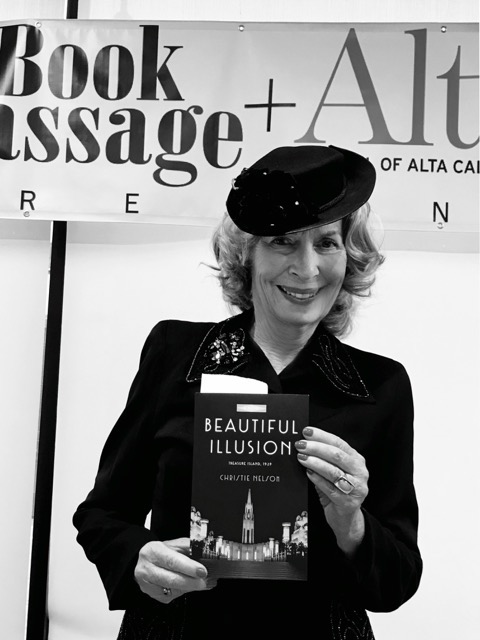

About Christie Nelson

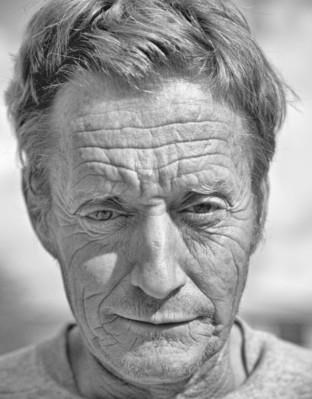

Christie Nelson ,1963, by Jack Welpott, used by erstwhile The Tides bookstore, Sausalito, for cover of their highly regarded literary magazine Contact. Reading at Book Passage Corte Madera, CA from her historic fiction novel in 2018.

Christie Nelson is the author of three novels, including Beautiful Illusion: Treasure Island 1939. Christie Nelson was born and raised first in the San Francisco’s Marina and then in the outside lands of Park Merced, within earshot of the roar of the lions in the zoo. She’s a graduate of Dominican University where she was influenced by the beauty of Marin’s wooded valleys and the majesty of Mt. Tamalpais.

While other dreams and forces took her far away, there are no places that have imprinted her as deeply as San Francisco and Marin. One part of her wanted to travel, another part wanted to dance, and yet another part wanted to write. In the end they each won out. Christie was last seen in these pages with her Mediterranean travelogue — Fall 2018 issue.

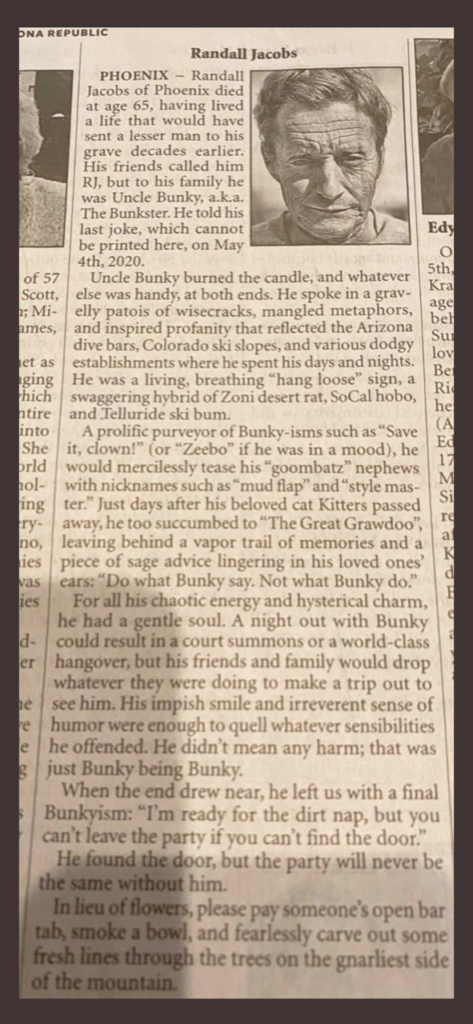

And, the Pulitzer Prize for death notices…goes to…

“Uncle Bunky burned the candle, and whatever else was handy, at both ends,” obited Jacobs’ nephew, Chris Santa Maria.

“When the end drew near, he left us with a final Bunkyism: ‘I’m ready for the dirt nap, but you can’t leave the party if you can’t find the door.’ “

It’s officially gone viral. “To commemorate his uncle’s fearless life and times, Santa Maria is now working with O.H.S.O. Brewery in Phoenix to produce a beer in his honor. Taking things a step further, Santa Maria and O.H.S.O. Brewery barrel program manager… hope to donate proceeds from Jacobs’ brew to local dive bars struggling amid the coronavirus pandemic.” From Janine Puhak, Fox News report.

Metafiction by Jeff Kaliss

Inspired by Bob Will’s legendary hit song “San Antonio Rose.” Wills, the bandleader of the “Texas Playboys,” is considered the co-founder of Western swing and was widely known as “King of Western Swing.”

Thing about being a muse is…

Thing about being a muse is: there’s no retirement, no vacation, nothing like that. Time off ain’t really time off, it’s more like just looking for someplace to be. If that sounds easy to you, just remember you’re a human being reading this, you ain’t no muse. Even though, if you’ve somehow been tricked into reading this story, you’re probably one of those types who’s had the hots to find a muse, for most of your supposedly creative life.

I know, I shouldn’t be that way with you. Listen, I hope you do find your muse, whatever you’re looking for, and that you deserve each other. Hey — have you imagined what a muse looks like? Do you want him to look like that smiley dark-haired guy you watched grasping an IPA at that bar downtown last weekend? Should she be wispy but strong, with long legs and a small hand to guide you on to enlightened bliss? Or maybe something like that exotic je-ne-sais-quoi you wanted to get to dance with at that club in the gay part of town?

Ha-ha. Just thought I’d ask. Well, no, you don’t always have to see a muse, but for you humans it’s probably better if you think you can. Me? Hell, you can see me anyway you want, and probably a lot of folks have. And I’ve been changed up by Whatever Does the Changing, over the millennia. Muses sound different to different folk too, did you know that? Do I sound a little “country” to you right now? That’s no accident, ‘cause for this ride, I’m gonna let you see what happens with one particular (and particularly famous) country-and-western song and one particular country music artist, just so you can see how it works. You college types have always fantasized about riding with a cowgirl, or being one, but you never were able to find a cowgirl or a horse on campus, were you? Anyway, if it works, you can just think of me as your Cowgirl Muse, for this short ride. Are you down with that?

Oh, and where we’re going? The song I was talking about is “San Antonio Rose”. It was the biggest hit, long before most of you were born, a big hit for a very successful songwriter, fiddler, bandleader, and sometime cowboy movie star named Bob Wills. Here’s a bit of what you call “encyclopedic” stuff: Bob Wills, who was born and lived in Texas for much of his life — 1905 to 1975 — created a music called Western Swing, because of how it tied up traditional instruments and melodies in jazzy packages. More western than country, really, Bob never did cotton to country. Though when he was a kid, he did pick cotton, in Texas. That’s when he also started picking up music and jig-dancing from the Negro kids who were out there with him in the cotton fields. Aside from the blues, Bob was never a guy hung up on color, not where it came to the skin color of anybody sharing music with him.

“Rose,” the sound and sway of it, came into his life at the start of his career, long before all that fame, around 1927 or ‘28, just before his and Edna’s little Robbie Jo came into their lives, when Bob was still cutting hair over in New Mexico, amongst a bunch of Mexicans. He found himself sweeping up the sounds of their fiddles and the rhythm of their polkas, along with their locks of lovely dark hair, and the tune that he borrowed, he titled it “Spanish Two Step.” And that’s all it was, a fiddle tune — no words. Me, the Muse, his muse, I helped him out with that, slithering around in his brain and making sure he got the modulations right — that’s when a certain section of a song shifts to another key. He wouldn’t have seen me, though, except maybe when he’d been hitting the bottle, which was his one bad lifetime habit, if you don’t count an allergy to monogamy, and maybe you should.

Anyway, around Thanksgiving time, 1938 — Bob was onto his third wife and his famous Texas Playboys big band, probably spending a lot more of his love on the latter — Columbia Records, that big business in New York, decided Bob Wills needed to wax some fiddle tunes. And Bob, who had fiddle strings going back in his family for several generations, was only too ready to comply.

What was I up to? Well, when I wasn’t helping Bob get out of barbering, I was musing around with a bunch of other musicians. I was beginning to notice — and it was rather to my satisfaction, I may tell you — that those artificial useless fences human beings set up between different kinds of music were beginning to collapse. Country music was grazing over into pop music and vicey-versey, long-haired Jewish guys like Aaron Copland were putting country into classical stuff, and so forth. I had a lot of fun stirring up people’s souls and integrating their minds, racially and otherwise. The Lord’s Work, if you will.

So now Bob needs me again. He’s yearning back towards that “Spanish Two Step” I got him hooked on, but his Columbia boss Art Satherley wants him to rename it “San Antonio Rose,” to give it regional flavor but keep it inside the U.S. of A. Couple years later, there’s even more interest in that old shit-kicking tune: Fred Kramer, from Irving Berlin’s company, also back east in New York — this is just about the time Mr. Berlin, another Jewish show biz guy, was dreaming of a “White Christmas” — this Kramer offered Bob three hundred bucks to put lyrics to that “Rose” tune. Kramer’s people would publish the song, and then Bob and the Playboys could record it. None of ‘em had any clue how big it’d be.

But I had a hunch of what would happen, as soon as I saw how far Bob had gone with my inspiration. That word, “inspiration” — you smarties may know this, but you should take note of it again while I have you on the line — comes from “the immediate influence of a god,” and even further back, from “breathing in.” Breathing in. Try it. Consider it your creative yoga workshop. Better breathe out, too.

And now, listen and learn. ‘Cause I’m gonna try to show you how it worked with good old Bob and his hit song, and with the rest of those Playboys, at that session in the middle of April 1940 in Dallas, Texas. America was pulling out of the Great Depression, and wasn’t yet in the War, it was pretty happy times for Bob and everyone else, despite his problems staying married and on the wagon. This “Rose” was a tune, remember, with history for Bob.

So, here’s how muses work with this kind of thing, how we can do stuff you can’t, unless you sort of recruit us. Some of what we do, is with stuff that’s been lying around in someone’s soul for a while. Some of it is what you’d call in-the-moment (there’s your “inspiration”). Some comes from other souls you’re keeping company with, or used to keep company with, it just kind of rubs off on you. Some totally flashes in and out of time and place, so fast, so pretty, you can’t even tell the hell where or when you are. Or even who you are. Are you Bob? Andrew?? Philip?? Gloria??? Well, you don’t have to be able to tell, not most of the time, and not right now. Just enjoy the ride with this Cowgirl Muse. Even if you don’t know this Western Swing classic (yahoo, there’s always YouTube), see if you can make out how I managed to herd Mr. Wills into the aromatic pastures of creation, into leaving himself and his band and the rest of the human race something they could love as long as they keep listening to it, a bouquet of sound. Here’s the music and meaning and magic of “San Antonio Rose!”

*

I have Bob start this song in the key of B-flat, which is good when you have horns in the band, and the Playboys have a slew of trumpets and saxes, something you wouldn’t get with your run-of-the-mill country string band. But the first thing you hear — it might have been on one of those old scratchy 78 rpm shellac discs — is Twin Texas Fiddles, in this case Jesse Ashlock and Bob, invoking the melody of that old “Spanish Two Step.”

Lots of open fifth chords, they’re not crowded chords, they’re open and rather sweet, like sucking on a piece of sugar cane from down on the Rio Grande. I remind Bob that you can start opening your heart up in those chords, big enough to polka through with whomever or whatever you’re in love with, sweet enough to sweeten your tears of joy. I get Bob to work every part of his top-notch band, like a fit cowboy with all his body parts ready to ride in a rodeo or make love. Listening, your heart gets pumped by Son Lansford’s big boy bass, your joy gets all the time tickled by Al Stricklin’s tinkly piano.

Need to be reminded that you’re in cowboy country, with a cute-as-a-button Cowgirl Muse? Okay: here’s a little slidey break on Leon McAuliffe’s steel guitar, and that brings on the first of Bob’s trademark high-pitched cry-outs of “A-ha!” You hear ‘em on practically all his recordings, plain as day. And they always sound somewhere between a wise-ass crow and one of the wild mules he used to mount when he was a little dark-eyed tyke in West Texas. “Some of ‘em was dad-burn hard to ride,” Bob said about those animals once. The grown-up Bob, when he gets on top of the music and brays this way, is maybe thinking both of wild mules and wild women, and maybe a bit of the Wild Turkey he had a few nips of before he began the recording session.

But Bob, the song is moving on and you have to get back to your half of the Twin Fiddles, before Tommy Duncan starts in on his vocalization of the lyrics, in that I’m-as-solid-and-straight-as-a-pine-tree kind of baritone-tenor of his: “Deep within my heart lies a melody . . .” That melody, in this song, has already had two beautiful rises and falls, like the two pretty ears on a cantering horse. Bob urges here, “Ah, tell ‘em, Tommy!” ‘Cause this story is gonna be everybody’s story: Bob’s (who wrote it), Tommy’s (who sang it), and even you folks’s who’re reading this now and will be listening to Bob and Tommy on CDs or the streaming service du jour later on.

“A song of old San Antone,” Tommy stays singing. For six beats, Tommy holds the long ‘o’ on the last syllable of that colloquialized name for that South Texas city, sounding like an owl perched on the famous but broken-down wall of the Alamo, which, you might not know, is now within walking distance of the San Antonio Holiday Inn. History lesson? Product placement? Indulge me, and enjoy it.

“When in dreams I live with a memory.” Same chord structure as the first part of the tune, but with a change of the melody line; that’s nice, Bob. Like the different ways you find to tell a guy you love him, when you’ve been loving the same guy for a long time. And Bob shouts out, “Yes, yes, go on!” because he’s in on this dream, he wants you in on the dream, that’s why you row-row-row your boat and ride your wild mule.

“Beneath the stars all alone.” All alone, in the middle of the Lone Star State. You’re in a star, as well as beneath them. Does that help you belong to eternity? And you’re resolved, on the tonic B-flat note. But not for long. Because love, or the looking for love, will never leave you alone, Bob.

Here comes yet another stroll along that same chord progression, with that flirty shift from B-flat to B-natural on the C7 chord, which always makes you think, Oh, what’s this then? Ain’t you cute, to ‘B’ so “natural??” “It was there I found, beside the Alamo” — I told you — “Enchantment strange as the blue up above.” Isn’t it enchantment which makes the blue strange, though, Bob? That’s what happens when the love which wouldn’t leave you alone gets under your skin. It fills an ordinary unclouded blue day with rainbows and clouds that look like pillows you’d like to lie down upon with her or him.

“A moonlit pass that only she would know.” Did she know it before you took her out there with that rough striped blanket, Bob? Would it matter if she did? You might be the better for it, actually. “Still hears my broken song of love.” Resolved back on the tonic B-flat, is Bob resolved to have to walk, or ride, through that pass alone, with a broken song? Well, in a lovely lyric like this one, it probably makes for a better story ballad than just trotting back down the pass with some new, quick señorita or caballero or cowgirl or cowpoke or whoever.

Now, here comes the part of the song where it shifts keys, from B-flat to its dominant key, F. It’s an irresistible thrill! Bob might have looked for this kind of thing in a bottle, sometimes. But, we might say, if you’re from a different part of the Southwest, it might be like the fireworks in your brain, after you chewed up that peyote you copped from a friendly cactus and got past the obligatory puking. You’re still polkaing, or two-stepping if you prefer, but you’re in a higher key!!

“Moon in all your splendor, know only my heart.” My heart is now the splendiferous moon! Metaphor without simile! And with a blare of jazz which Bob imported from New Orleans, or maybe even New York, where Charlie “Bird” Parker would have just gotten “Cherokee” off the pop reservation and had begun to rebop it under his title, “Ko-Ko”. With my recommendation as a hybrid breeder, Bob makes sure we hear the jazz in the trumpeting of Everett Stover and/or Tubby Lewis. It animates that moonshine! (Sidecar (or is it sidebar?) : Did you know that Bob was part Cherokee, on his mom’s side, and that he had another hit with “Cherokee Maiden,” a year after “Rose”?)

“Call back my Rose, Rose of San Antone.” This Rose, whoever she is, is the heartthrob of the title, the girl in so many guys’ song lyrics. And maybe, with that F modulation, the guy’s heart is throbbing loud enough to sound like a tom-tom, or tambora, or whatever Rose’s people respond to, and to get her to give the guy another chance. Bob?

“Lips so sweet and tender, like petals falling apart.” C’mon, Bob. “Petals?” Wasn’t Rose a little bit more actively involved in the kissing thing? Yeah, I know, it’s supposed to be your song, as your Muse I should know my limits. Or should I?

“Speak once again, of my love, my own.” This time, the long ‘o’ is holding (four beats) on the note, E-flat, which returns the song to its original key. And after the high of the ‘F’ bridge section, it feels like a homecoming, a lying down on your own bed, with or without Rose, but with different words, words of consequence for this romantic musical quest.

“Broken song, empty words I know.” Another reference to a broken song, but here’s where we, the listeners through time, may have to stand apart from the forlorn teller of this tale. Because, to our ears, the song has been as strong as it has been stirring, and the words maybe fuller and lovelier than Rose ever was or could be. I’m taking some kind of credit for that, folks.

“Still live in my heart all alone.” No, not alone, because your heart harmonizes with our hearts, and in big bands and in timeless tunes, the glow in the company of other folk shines on the cold silence of mortality. “For that moonlit pass by the Alamo.” We’ll ride it with you, Bob, again and again, after we toke up behind the Holiday Inn. “And Rose, my Rose of San Antone.”

After finishing his sing-through of the song, Tommy is comforted and congratulated by Bob (and by me) by means of a snappy guitar solo by Junior Barnard, a white man in a Stetson, channeling Negro-electric-guitar-pioneer Charlie Christian. Listen to how Bob moans over Junior’s magic. That’s a moan of color-blind delight, and maybe the pride of a bandleader who has led his boys where no band had gone before, and likely would not go again.

Then, there’s a flashback to that high bridge, the splendor this time shared by a mini-choir of cowboy angels — three guys, not identified in the notes but credited in our memories — and Bob jazzing and fingering his fiddle to a climax way, way up on the fingerboard. Finally, with no need of pretension (this ain’t the Basie band), Tommy finishes with a reprise of the song’s last four lines.

*

And there you have it. How a muse works through some good music. Did I already tell you that ‘music’ dates back to the Greeks, where it meant, “the art of the muses?” Though, I don’t think they had much to work with. Could you have squeezed out as much joy as Bob Wills did, if all you had was a lyre and pan pipes? Maybe, it you’d squeezed enough grapes to go with it.

But I’m sure all you writer types are hoping that a muse might make herself available for more than just music, and you’d be right about that. Or “write about that,” for a cheap wordplay You gotta give me that, I’m a little tired. I told you, we don’t get any vacation, like you guys do. Remember this: Bob loved mules, and ‘muse’ is only one curvy letter away from “‘mule.” Much obliged.

(Dedicated to Andrew Joron and his Speculative Fiction Playboys and Playgirls. Joron is a writer of experimental and science-fiction poetry and was of the circle of late Surrealist poet Philip Lamantia. He currently is in the Creative Writing Department at SFSU.

END