“We planned to cover 1,100 miles from Lima to Ecuador in one week and attempt some of the longest waves anywhere.”

“Fortune goes to the prepared. Disaster hunts the others.”

Down to Peru

by Tom “Longride” Fitzmorris

Rockaway Beach, Pacifica, CA, February 20

“You might have more fun if you don’t always chase the longest waves,” my best surf-buddy Nick yelled. “Or the toughest.”

I dragged myself and half a surfboard onto the black sand of Rockaway Beach. We were just a few miles north of Mavericks’ legendary giant waves.

“Damn, a pit opened up in front of me.” I said. “I wrapped my legs around the board bronco style, leaned backward to avoid going in. The lip of the wave guillotined my board in half!”

“I saw the other half getting sucked out in the rip-tide. It’s gone.” Nick said. “That’s why I came in early, too many ‘pits of doom.’”

I partially unzipped my wetsuit and sat down on a big rock next to his. I took some deep breaths. “Part of me wants to be as good as I can,” I said. “I got attention as a kid by being good at things. Be the A-student, do my chores. Now, chase waves.”

“You must’a been a boring kid.” Nick laughed.

“When I was eight, my mom forgot to pick me up after a Cub Scout meeting,” I said. Twenty minutes I had stood on an empty street, only the full moon for company. “When I walked in the door at ten p.m. there was Mom and my seven siblings. She apologized. Not only did she forget to pick me up, she hadn’t even noticed I was missing.”

“Sounds like you confused being good at something with being Good. It’s always the parents, ha ha!” Nick’s eyes twinkled below arched eyebrows as he gooned at me.

“This frigid water is so dense and heavy.” I looked out to the fog above the crashing waves. “We need to find some nice warm-water point breaks, Nick. Our surf trip to Central America was great but too hot. Hey, let’s go south. Let’s go to Peru.”

Nick leapt to his feet. “I’m in. Down to Peru, Tommy!”

Tongue Tacos

Santa Cruz, CA. April 18

Nick’s red Subaru slouched cliffside, our rooftop longboards visored the enthusiastic morning sun. Seagulls circled overhead, calling, “aylah! aylah!” as cool iodine-laden air puffed on-shore into the car, crinkling the skin of our faces with its coolness. Glare glittered off the Steamer Lane wave tops that rolled into the cove, rising feebly. An occasional wave broke into the cliff. Blip…blip.

“Well, it was a beautiful drive! April is chancy for waves, let’s have some tongue tacos!” said Nick.

Tacos made with beef-tongue were a specialty of our local post-surf dive Mexican restaurant. Nick always had the next good idea and after 40 years, still exuded joy ditching Chicago for northern California.

“Let’s keep going west, find some waves; we gotta stay fit for Peru,” I said.

I wore worry too easily because life was after all a contest. Both of us raised in big Catholic families, we knew Hell was real, but Nick’s “have fun since we’re all going to hell-haha!”contrasted my lifelong demon-wrestling and my, “even if we behave, we’re all doomed” vibe. But surfing, a “don’t tread on me” ethos, and fondness for adventure linked us.

We passed the Lighthouse into the Westside at Mitchell’s Cove. Three to four-foot waves rolled in crisply. Three surfers sat together. Nice wave, nice day, nasty locals? Hmmm… The further west in Santa Cruz the more heavily local the vibe, until out past Natural Bridges you better be Jason “Ratboy” Collins’ roommate and surf better than the locals if you are not known.

“Wave looks fun. Think they’ll heckle us or slash our tires? It’s your car,” I said.

In surfing the guy who drives is 100% responsible for his car’s fate. In return, he makes the ultimate surf spot choice. The question was half in jest but only half.

“Let’s try it. We’ll just avoid them, surf that inside wave,” said Nick.

Twenty minutes later we have both caught chest-high glassy waves. Glassy means our connection to the wave’s energy is perfect. We paint our ride with white contrail “S-turns” up and down the face. During the ride everything inside has that “ah!” feeling of plunging into cool water on a hot day. The set has emptied the lineup as each surfer caught a wave. Seduced by empty outside waves, we abandon our “avoid-locals” strategy and paddle out to their spot. Surfers clump together like the metal filings a magnet collects when dragged through kid’s sandboxes. Thus, Nick pops up on a wave and drops in on a local, already on the wave. Local-guy runs down Nick, shoves him aside, shouting something worse than “You ahoy, you dropped in on me, get the fuss out!”

We embraced our moral failure and paddled in, additional friendly local surfers’ farewells chasing us. We fled to the car, peeled off wetsuits, and loaded our boards on a war footing.

“I’ll buy you some tongue tacos. Forget about your wave of shame. Let’s go celebrate your intact board and tires,” I said.

Las Palmas’ non-rancid cooking oil, tongue tacos, Negra Modelo and a West Cliff Drive location made it the best such Mexican grill. Actually, the only such. The family took over a fried chicken shack in 1974, apparently only removing the abandoned cars from the parking lot, then lit the fryers. Ever since, they had resisted any remodeling urges. We always went there after a glorious surf. Today we mostly needed a beer.

“Tommy, surfing’s not supposed to be this painful,” said Nick.

“You know, in the real world you didn’t do anything wrong, you only broke a rule in the surfing world. So now that we’re here eating tacos did you even break a rule?” My second beer was clearly beating the tacos in the race into my bloodstream.

“That’s deep,” said Nick. “I’m cutting you off.”

“Remember that time, out by myself, I got hypothermia?” I asked.

“You were starting to chase bigger waves,” said Nick.

I had been surfing Middle Peak at Steamer Lane, Santa Cruz’s iconic break for about two years and improving to where on this day I was taking on waves whose faces were eight to ten-feet high. The best northern California surf comes in the fall and winter. This was a cold winter day, 48-degree air, 52-degree water, in a wetsuit that in hindsight was spectacularly inadequate.

“You know the drill, sit outside Middle Peak watching the horizon, the approaching sets. The first decision is, can you make the wave?” I said.

“And if you can’t, whether to paddle left or right to outrun it—or it lands on your head!” Nick shouted into the bottom of his second beer. Nose-ringed patrons stared, mid-taco.

“Exactly,” I said. “I waited too long to move; took two waves on my head. Some local dude volunteered, ‘kook, you don’t belong out here.’ He meant that I sucked, but he helped me understand I wasn’t reacting to the oncoming waves.”

I had paddled in. Then with one foot on the rocks, the other in the ocean, five minutes to wrap my leash around my board. Only then did I understand: I was so cold I didn’t know it. Padding toward those frigid waves I was that deer who stares into oncoming headlights after foolishly jumping onto the road. Cognition had retreated in the face of hypothermia. Reaching my Jeep, I was too weak to remove my wetsuit. Drove the forty miles home, heater blasting.

“So, you’re telling me you were a fuckin’ idiot. But you still ARE an idiot, so I guess you didn’t learn!” Nick guffawed. Nick grew up in Chicago and when he laughed, this origin was evident. Like a Brooklyn accent but with more corn. More “cuoffee” than “coffee”.

“We’re about to travel across the world to surf, you’re dropping in on guys, and I can be reckless,” I said.

We planned to cover 1,100 miles from Lima to Ecuador in one week and attempt some of the longest waves anywhere.

“For me surfing is not just the wave and Peru’s more than just a surf trip, said Nick. “Don’t surf anything that you’re not up for. I won’t. You’ve trained hard. You have the lung capacity of a dolphin. Heck, you’re drown-proof. We’ve already paid for the guide and the airfare and, WE’RE GOING TO PERU!”

Points South

Surfing in Central America can be challenging, with its faster, hollower surf–especially for us fifty-year-old longboarders. So, two years prior, we had surfed the “Seven Sisters of La Libertad” the famous pointbreaks along the Salvadorian coast. By 2008 El Salvador was relatively safe if one surfed with a local. We had Wilber, the Central American Longboard Champion. All the thugs were his friends. The surf was fabulous, but there are only two air temperatures: muy caliente and “oh my God!”

So where next? In spring if one heads far enough south it becomes fall and cools off. The southern equatorial current keeps Peru dry and temperate.

Down to Peru

Sixteen hours: SFO-MIA-LIM, we landed at ten p.m., dragged our gear to the domestic terminal gates, rested on our boards for the night, surf bags as pillows, snug in fleece jackets.

“You know Nick, I started surfing because it was fun, continued surfing for the thrill; now I surf to collect memories. Ten years ago on Kuai I surfed during an amazing sunset. The entire face of that wave glowed, mirrored lemon-yellow sunlight into my face. I can replay that right now.”

“Tommy, please replay it quietly. I’m sleeping.”

My Manic pressed on. “I’ve wondered what creates recall experiences. Maybe the brain stops thinking and the body experiences the world directly, experiences the wave kinesthetically. The cost is I may take my body places I shouldn’t, maybe you too.”

“Like this terminal in the middle of the night.”

Overcome by fatigue, we non-slept fitfully under buzzing mercury lights and air-conditioned breeze, until the rosy fingers of dawn peeled our eyelids open three hours later.

Prescience

Peru day 1, May 10

A red sun popped up over smoggy Lima as our plane headed for Trujillo. A glowing tanned man with a surfboard awaited us at baggage claim. This was Riquero, our Incan-god surf guide.

A blue Toyota Corolla crouched outside. We loaded up and headed into bad-ass Trujillo. Riquero drove with vigilance. The streets were gravel, the locals sullen. Our ridiculous rental Corolla-with-longboards ensemble shouted “not-local.” Crammed in the back seat, I asked Nick, “If we fall off a Pacasmayo wave during a big swell can we catch the next one? I counted seventeen waves in one photo!”

“I’ll bet you can get back on them anywhere in the bay. I wouldn’t worry,” said Nick. Knowing better, Riquero pretended not to hear. After all, drownings were rare.

“I had a dream last night,” I said. “I fell off one of those waves. Wave after wave came, all uncatchable. I was caught inside endlessly.”

“How’d you get out?”asked Nick. Riquero kept quiet.

“It was so disturbing, I woke up,” I said. “Once my brother-in-law, a competitive swimmer, was bodysurfing in Hawaii. He got caught inside a ten-foot wave and was held under for three or four more. Said he almost drowned while his family watched. They had no idea.”

“What happened?” asked Nick.

“Every time he went under, his blood-oxygen dropped further. Not enough air-time to recover. One more wave, he’d have drowned. Fortunately, the set ended first. The ocean let him go.”

#

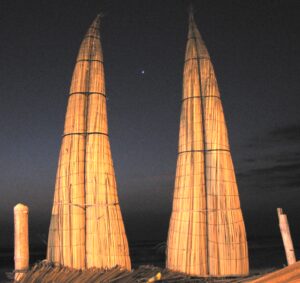

Ninety minutes north, Pacasmayo hove into sight. The pleasant seaside fishing community sits on the bay, bordered by a point, off which peel some of the planet’s longest breaking waves.

Storms rise up in the Southern Ocean far below Chile. Sixty knot winds can blow for days across vast distances. After 5,000 miles, wave energy has organized itself into widely spaced corduroy energy lines in northern Peru. Near-shore shallow water causes waves to slow, so as open-ocean swell encounters a point, it wraps into the bays along the coast…. Pacasmayo and Chicama bays have perfect sandy bottoms so the waves can peel for a mile. On a big south swell the sets virtually never stop. Fortune goes to the prepared. Disaster hunts the others.

Caught Inside

Peru day 2, May 11

“My friends, let’s go surf.” Our Peruvian surf-god guide greeted us. Elegant nose, deeply bronzed skin and impressive biceps, Riquero appeared as if he had stepped off an Incan frieze. “Are you ready for good things?”

Awaiting us in front of the hotel was the blue Corolla-with-boards at the ready.

From a bluff we studied our Ocean at El Faro, Pacasmayo’s main peak. Ten-knot side-offshore winds turned the water steel grey-blue, rippling her surface. Waves twisted into rolling lumps with seven to nine-foot faces. She looked tricky.

“Nick, we slept overnight in the terminal, I still can’t remember a single wave I surfed the next morning, and we’ve surfed four times in two days. But we only have two more sessions with long waves,” I said as I swept my hands across the water.

“So, you need to go more than you want to go. Sounds like a bad idea. Tommy, your manic OCD is flaring up!” Nick laughed.

“I’ll go if Riquero does and if we ride the Zodiac boat.” The waves peeled so far that local entrepreneurs sold rides on rubber pontoon boats with outboard motors to run surfers out to the break.

Riquero and I paddled out. Nick watched. We caught waves, rode the Zodiac back out together buddy style. Inevitably the ocean and the 300-meter rides separated us. I surfed well but fatigue was building. The sets were getting bigger. On an eight-foot wave under a windy blue sky I floated on the lip a second too long. The wave left me behind. I waved at the distant Zodiac. No one surfed where I was, so they never saw me. Disappointment peeled away my energy and exposed my core fatigue. Caput. The water wasn’t cold, but I felt clammy. My fingers wrinkled and numbed as my body protected its core temperature. Just as a fan blowing across a pan of water in the warm desert can freeze it, so too can hypothermia attack a fatigued surfer in temperate conditions.

Too tired to paddle out, I aimed for shore two football fields distant. The horizon disappeared behind stacked set-waves barreling toward me. Hopelessly out of position, I paddled grimly, forcing tired muscles. Too steep to catch, the oncoming wave collapsed in a cataract that drove me eight feet down. Folded, I tumbled in green darkness…

The Red Crab

Popping up, I pull my leash to fetch my board. Remarkably, a battered half-a- surfboard floats nearby, a little red crab perched atop. I hoped the guy made it in ok on the other half. How long was this board abandoned that a crab could be perched on it? I shiver but feel less alone.

Ten seconds to catch my breath, suck in iodine-seaweed scented air as I paddle. The swell was hitting, sets getting bigger. Second wave approaches, nine-foot, lifts my board. Paddle quicker! My board lifts, accelerates, but the wave’s lip, already pitching, drives me under. Fuck! Tumbling, ears-pressured. Caught my leash, climbed up to the surface. Red Crab’s board still floated shoreward. He scurried up onto it. If he can do it, I guess I can, I thought.

I tamp down fear lurking in my mind. It’s possible to catch waves with a “no-paddle take-off.” The third wave’s shear face, ten foot, levitates my board. I have trained for Peru, but fatigue and oxygen debt rob leg strength. I end up on my knees. This is the worst position in which to attempt a fast-breaking wave. Pitched. Ocean holds me under carelessly then releases me, but her waves keep coming. Too much time underwater, blood-ox low. Hard to think.

Struggled onto my board, notice Red Crab is gone. On my own. Fear pops up out of my subconsciousness: my prescient dream from two nights back was being fulfilled. I attempt to boogie-board. Fourth wave thunders, hammers me deep. My buoyant board tombstones vertically above the water. The leash stretches, then severs as the collapsing wave presses me under. Vision-narrowed, time slowed, world shrunk. Like a shark, Ocean has no mercy. She is beautiful, but she consumes.

Fetally tumbling.

Eternal chaos.

Board gone, I hit seafloor. My fear was replaced not by panic but rather by melancholy. A cradle-Catholic, I have an abiding belief of a God from which I was created. This did not mean my request would be granted, but I knew I was not broadcasting to an empty universe when I prayed to God, “Help or I’m going to drown right here.”

I was out of oxygen and ideas. I submitted to the Ocean, as my cognition faded. My mind left my body to fend for itself in the present. It re-inhabited that crystal lemon-lit wave I rode in Kauai a decade prior. Vision-narrowed, time slowed, world shrunk.

Sputtering, gasping, I popped up, vision dark, board gone. Fifth wave loomed. Broke. Pushed me forward. I swam and was pushed the last fifty yards to shore. Ocean had delivered me. Nick descended the bluff, rescued my board and greeted me.

“Looked tough out there,” said Nick, sympathetic but unknowing.

“Not good,” I said, empty-faced.

Ten minutes later Riquero emerged dripping. A glistening, grinning surf god. “I lost you out there. Good surf?”

Alone hours later, I stared out at the wine-dark sea, breaking waves bouncing sound-thumps off the hotel’s front porch walls. The rising moon glittered ruddy light off the wave tops. The night before Venus had hovered in the twilight sky poised between two Huanchaco boats, like set waves, an omen that I had missed. Venus, the goddess born from the sea, and the epitome of the feminine which drives men into chaos.

Nick appeared, offered a beer. “Don’t beat yourself up Tommy; you surfed well.”

“I broke the cardinal rule: self-reliance.”

“No surfer can predict everything,” said Nick.

“Perhaps. But I was one hold-down from drowning and couldn’t save myself.”

“Tommy, that set was endless, so why did it stop? I think God let you go.”

I wept quiet tears. No one said anything. Fragility of spirit present. Ocean’s waves glittered moonlight. Cool salty air wafted onshore, filled the porch. Geckos watched with wise understanding perched astride the walls…

Wind thrushed.

Waves thumped.

Moon.

Silence.

“Do you remember the night of the millennium’s first full moon?” asked Nick. “We surfed Cowells until dark, then floated, waiting for moonrise. All those cliff-top crystal-chanting, bongo-drum players, the smell of ganja.“

“Yep, everyone went quiet when the sky started to glow, then the cheering when the moon’s edge appeared.”

I remembered the spark of that moon’s crimson light had grown into a ruby line on the water straight to us. Mother moon’s red tendril.

“Surfing’s not just the ride. It’s fun waves with friends, and tongue tacos at Las Palmas afterwards,” said Nick.

I walked to the porch rail and looked out at the night sea, her wavetops now golden.

“Remember my dream in the airport, of being held down? How is it my mind then, knew what would happen today?” I said.

“You’ve had a deeply meaningful experience. Maybe meaning is beyond time. Or maybe events in time ripple forward and backward. But is it worth it to push yourself so hard? You said yourself you can ride that Kauai wave anytime.”

“Not obvious I have a choice. Part of me is driven to see across. In those events I think I’m glimpsing through Paul’s glass darkly; reality’s veil is lifted for a moment. True, the other part just wants a couch and a beer. Do you have any more?”

Big Day

Peru day 3, May 12, Daybreak

“Nick, Surfline says central Peru buoy is one and 3/4 meters every twenty seconds. Damn, sounds like double-overhead at the point!” I jumped up and down.

“Better start doing your pushups, Tommy!” Nick chortled.

Riquero and the eager blue Corolla bristling with surfboards sat together waiting out front. “Let’s go my friends, today is why you came to Peru!”

A chilly mist wrestled with the low morning sun and softened the Ocean. Horse-tail clouds aloft in cerulean sky flagged the offshore breeze. Southward, point after point jutted into the Pacific for twenty miles. Southern-ocean corduroy swell lines wrapped every point, endlessly marched past Chile, past Lima, past El Faro. It felt cold.

“Surfers get out on a big day in a Zodiac. Or paddle north from below the point, approach the wave from the sea. We don’t have a boat,” said Riquero.

We stood in wetsuits studying the waves, boards under our arms. Strong swells formed endless waves breaking vigorously. Nick eyed me; no one spoke what both felt: Crap, how do we get out, and what is waiting for us?

“Guys we wait for a lull, paddle like crazy, get out before the next set.”

We made it out to deep water where the swell rolled harmlessly under us then paddled for the point. I felt the break approaching because every few seconds the air itself pressurized my chest and face, very low frequency. The feeling-sound long-distance swell generates, unloading as the wave births. As each wave’s energy felt seabed, water sucked up the face, the top overran the bottom, then pitched fifteen foot down, water driving down through water.

Smooth water and offshore breezes were in our favor, and we sat safely twenty yards behind the wave’s peak. The wave’s back was an anxious six feet high. I shivered. Twelve guys already there. Nick and I paddled to Riquero, little chicks under hen’s wings.

“Auto-crowd” muttered Riquero.

“Brazilians always travel in packs, and they hog the best waves. They are good and very aggressive, so we Lima guys harass them back.”

Nick gathered his courage and paddled for a wave. A Brazilian cut him off, Nick fell, and the wave took him down. Riquero retaliated: he later dropped in taking the same wave as the Brazilian, knocked him off his board. Every Peruvian in the line-up knew Riquero. Every Brazilian did not know Riquero but recognized that this man was really good, really strong, and really Peruvian.

Guide or no guide, the Pacasmayo point break wave had room for only one rider. Surfers forced deep takeoffs into the wave’s steepest biggest part or even behind the peak. Intimidating when we’d never surfed this wave this big.

“Nick, this is like climbing down the side of a house moving eighteen miles an hour.”

“…while someone tries to knock you off your ladder. But: these guys are dropping off the waves early—they only surf the biggest section. 100 meters north we’ll catch empty waves,” said Nick.

Surfing is best approached with focused understanding, maybe compassion. Nick approached surfing with calm joy. We paddled to the waves’ birthplace out of the swell-lines. From down the line I watched Nick’s take off: he paddled-quick as the swell lifted his board. As the wave emerged from its swell-mother he popped up on the youngster before it grew too fierce. Nick angled down to the trough to bottom-turn then leaned on his left rail which shot him up the face. He was coupled to the wave. I followed on the next.

Like pumping on a playground swing we float up to the lip, board speed converted to height, then we rocket again down to the trough. For nearly a mile. The way is: stay with the wave. It is the energy source. Our bodies have main-lined our mind to Ocean’s waves. Empty cliff-lined beaches pass to our right for minutes. After each wave we ride beach jitney taxis back to inside El Faro point.

Two hours later I beamed, one foot in water, the other on land. Nick stepped off his board as it nosed into sand.

“Tommy, I can’t tell if your face looks like the sun or the moon, but it’s all lit up!”

“I’m done hurling myself into the biggest waves,” I said. “God answered yesterday, the Ocean today.”

Time for tongue tacos.

END

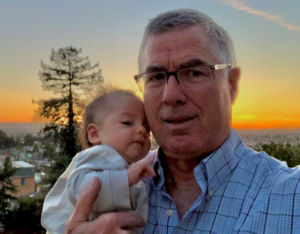

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Thomas Kenneth Fitzmorris is known to his surf friends as “Longride.”

Tom stepped into writing with Stanford’s Creative Writing program in the Fall of 2019. His second class was a workshop for which he wrote the memoir Down to Peru. His story was awarded Prose category second prize, in the nonprofit Blue Institute’s writing contest. Presented here is the debut of Tom’s expanded, revised and enhanced version of Down to Peru.

Tom’s second memoir, “Tolstoy for Knudsen,” premiered in MillValleyLit’s Fall 2021 issue.

A father of four, grandfather of five, his other passion is surfing. Beyond Santa Cruz and environs, Tom has surfed across the Pacific, Mexico, and several other Latin American countries.