A Journey Through Chaos and Beauty: Uzbekistan to Kashmir, 1987

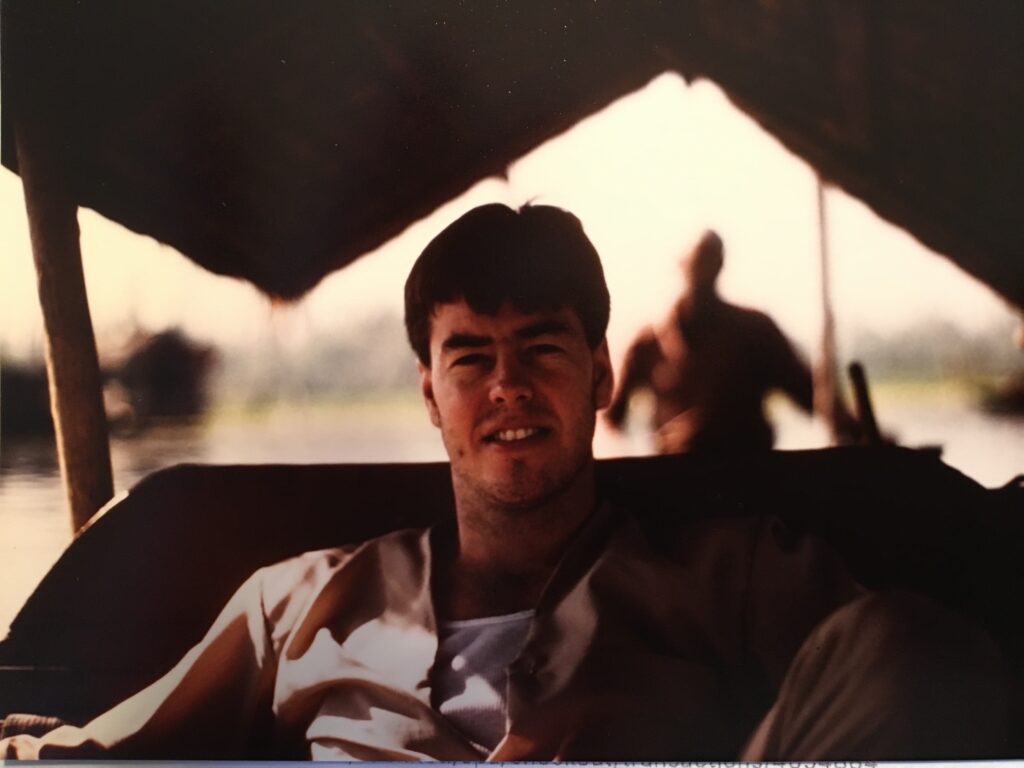

Adventure travel memoir and photos by Gene Fischer

In New Delhi I finally boarded a rickety bus. I’m exhausted after two days stranded at Tashkent’s airport in Uzbekistan. My flight on Aeroflot—mockingly called “Aeroflop”—had made an unscheduled stop there to offload Russian military personnel.

It was 1987, and the Soviet Union was embroiled in the Afghan War. Tashkent, I learned, doubled as a military transport hub. The young soldiers’ faces, etched with dread, reminded me of the haunted expressions of American GIs in Vietnam War photos from Life magazine. A lot of them knew they were not coming back. War’s grim reality was palpable—there are no happy endings.

Stranded in Tashkent

What was meant to be a brief layover turned perilous when the airport came under attack by local Mujahideen, armed with American-supplied Stinger missiles. They were shooting down anything that flew, especially helicopters. The Russians had to secure the area before we could leave, delaying us for a day. I didn’t mind if that is what it took to stay alive, safety trumped haste.

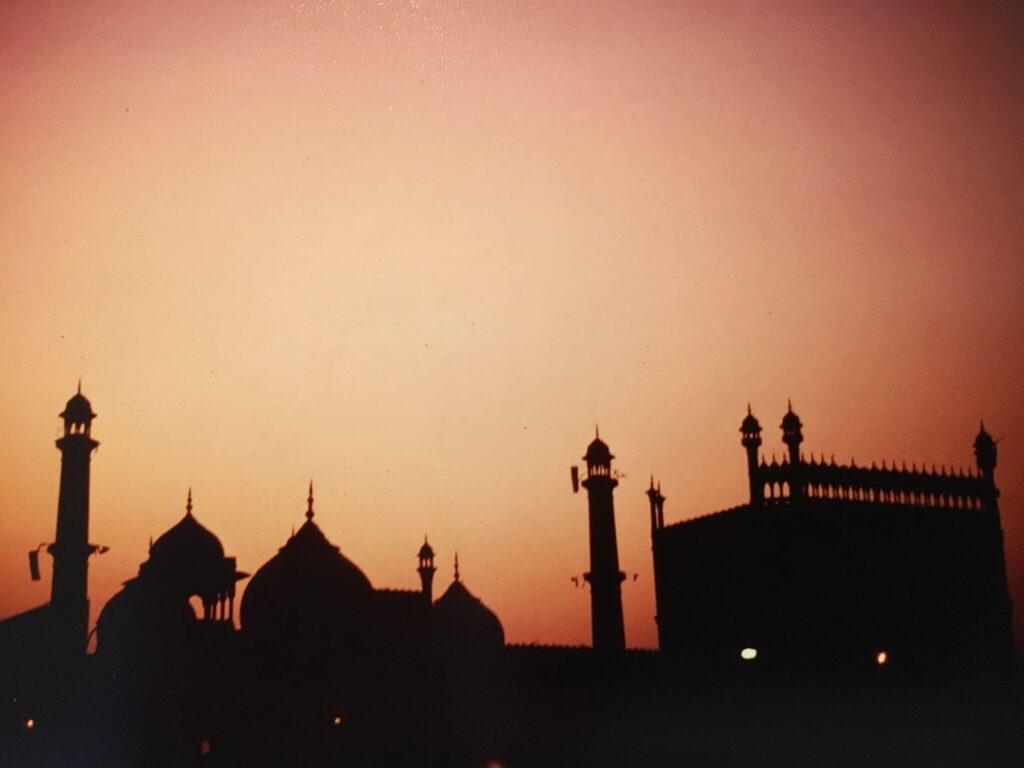

In Tashkent, I teamed up with an Australian, the only other Westerner on the flight. We stuck together, watching each other’s backs in an unsettling environment where Russian or Uzbek eyes followed our every move—even to the bathroom. The whole thing was very creepy. At 4:30 a.m., a piercing sound I mistook for an air raid siren turned out to be the Adhan, the Muslim call to prayer. Some heeded it; others ignored it.

After a tense wait, we finally took off for New Delhi, fingers crossed, prayers muttered. The flight was smoother, the food marginally better than the “slimy postage-stamp-sized fish meat” that was served on our route to Moscow. We were now flying over the Himalayas, we were entering a fortress of towering peaks, otherworldly and majestic.

New Delhi—A Chaotic Descent

Landing in New Delhi was like stepping into a surreal, chaotic time warp—think Luke Skywalker in the wild Mos Eisley cantina from Star Wars. The city was a frenzy of poverty, filth, and disorder. I grabbed my backpack and hopped on a local bus to a guest house that I had booked from a guidebook. The ride revealed a grim reality: thousands of homeless people lined the streets, their lives marked out by chalk on the pavement, like a scene from Dawn of the Dead. Hindu beliefs in reincarnation, tied to animals like cows, were evident everywhere.

Dumbfounded, I watch their sacred cows grazing beside starving children. Even more, the sky is swarming with vultures circling above, drawn by sky burials that is practiced by the other dominate religion over there called Zoroastrian. The whole scene and the juxtaposition of well-fed cows and a shriveled, starving infant on a dirt road haunted me, fueling nightmares about global hunger and overpopulation.

On the bus, I watched a man step into our path and is struck head-on. The driver paused briefly before continuing. I later learned that some, driven by reincarnation beliefs, saw suicide as a path to a better next life. This grim cycle is repeated throughout my journey—some accidents, some intentional. Shocked, I arrived at my guest room, a sweltering, mosquito-filled bomb shelter. Bushed and sweating profusely, I settled in, too drained to seek alternatives.

Finding safe drinking water was my next mission. Sealed plastic water bottles weren’t yet common. After some rest, I hired a barefooted rickshaw driver to take me around on a two-wheeled cart as he helps me locate a pharmacy that has safe potable drinking water. The food was another gamble—dead chickens and other various exotic animals hung on street hooks, swarmed by flies. There was no refrigeration. I stuck to boiled vegetables and rice with chai tea, the only options I trusted.

Getting back to the bunker, I sat outside under a strange tree—red-barked, like a madrona crossed with eucalyptus—watching aggressive ants march in formation like a Navy SEAL team. Everything here, from people to insects, felt alien. I was completely in a different world. That night, I wake up covered in ant bites, the fan had blown them all over me. Between nightmares, bites, and filth, I was fraying.

Overwhelmed in New Delhi

New Delhi’s relentless poverty overwhelmed me. Beggars—blind, limbless, or diseased—lined the streets, some mutilated by “owners” exploiting them for coins. The despair was crushing, and I needed to escape. I caught a train to Jaipur, en route to Kashmir, hoping for relief. The train ride became an even greater nightmare. Unknowingly that it was free for locals, it was packed beyond capacity, a claustrophobic crush of filthy bodies, odors, and bodily functions—sweat, urine, vomit. I vowed never to board another.

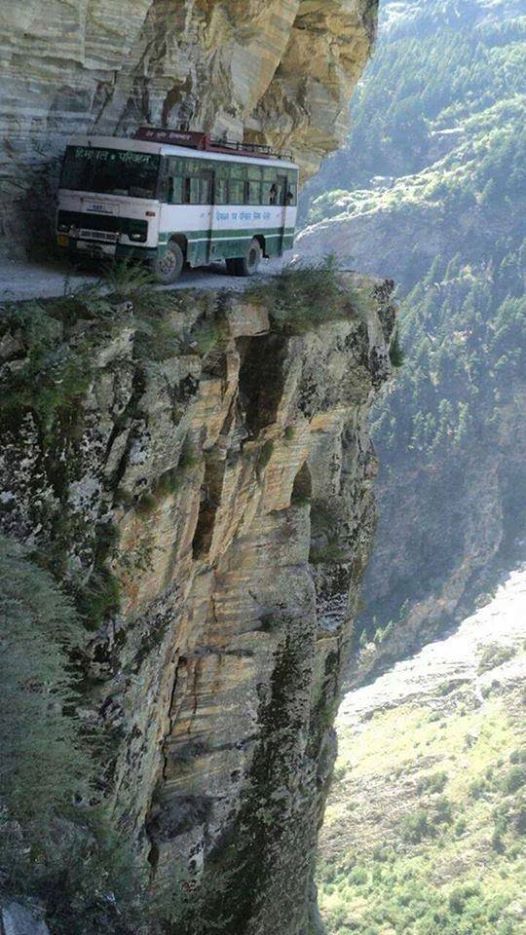

Getting off in Jaipur, I toured ancient ruins but quickly sought out a bus to Srinagar. The bus, a 50-year-old relic with no shocks or padding, was driven by a man blasting Indian music at deafening levels, seemingly unconcerned with death due to reincarnation beliefs. The faster he drove, the more trips he could make, thus more money. The road to Srinagar was among India’s deadliest, a narrow, cliff-lined path plagued by avalanches and wrecks. The driver’s reckless passing on blind corners forced passengers to disembark at times, fearing the bus would plummet.

I made the frightening decision to join some others on the roof, gripping steel bars for safety, passing a graveyard of crashed vehicles below. The year-round road crews that camped next to the highway were always standing and ready with their shovels to repair the road or more likely digging potential graves. The scenery was incredibly breathtaking, but the terror was insanely real. I was thinking that no one would ever believe me—if I ever got home. You could not make this up.

Kashmir: A Haven of Hospitality

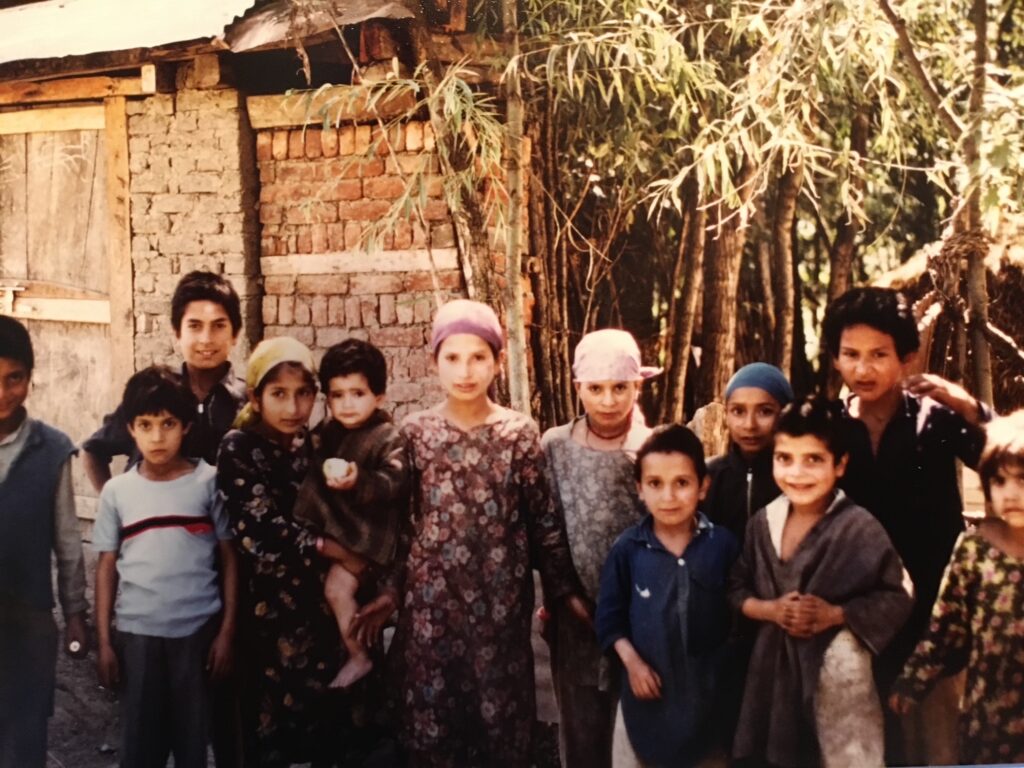

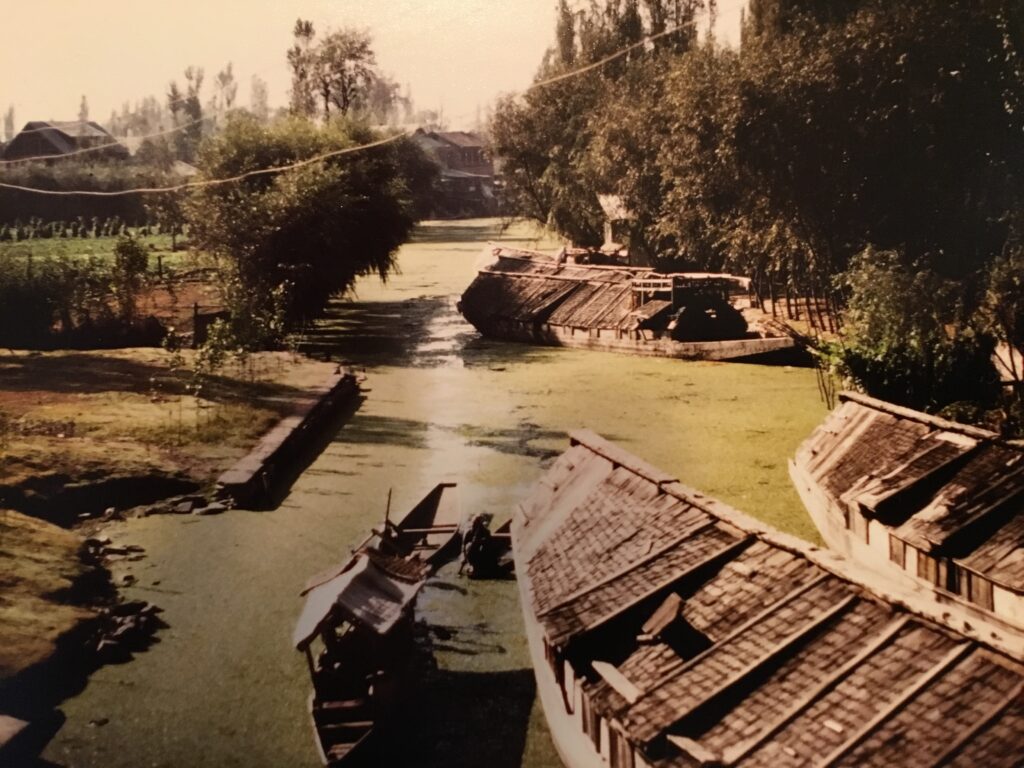

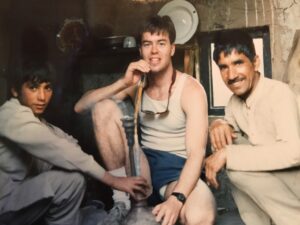

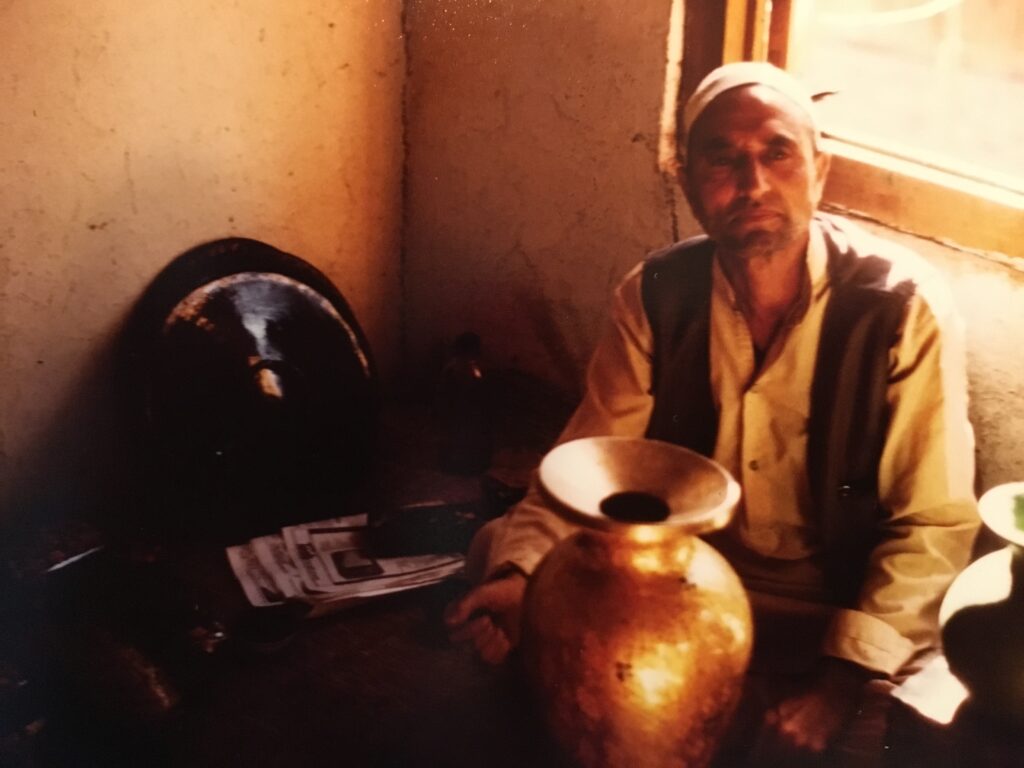

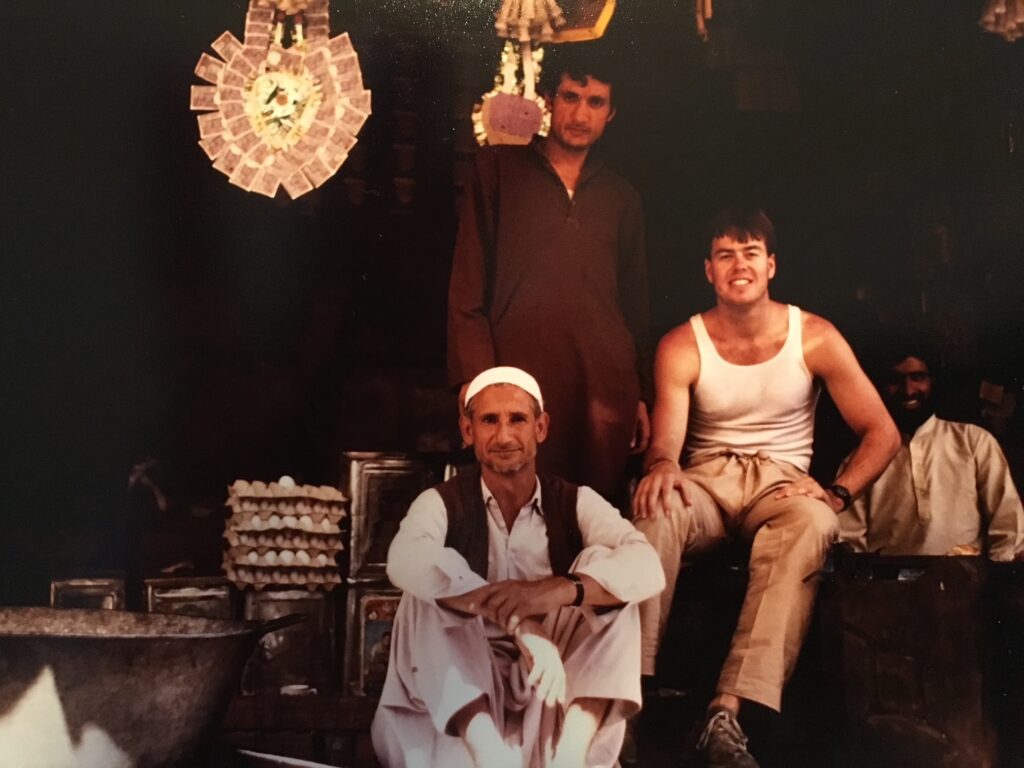

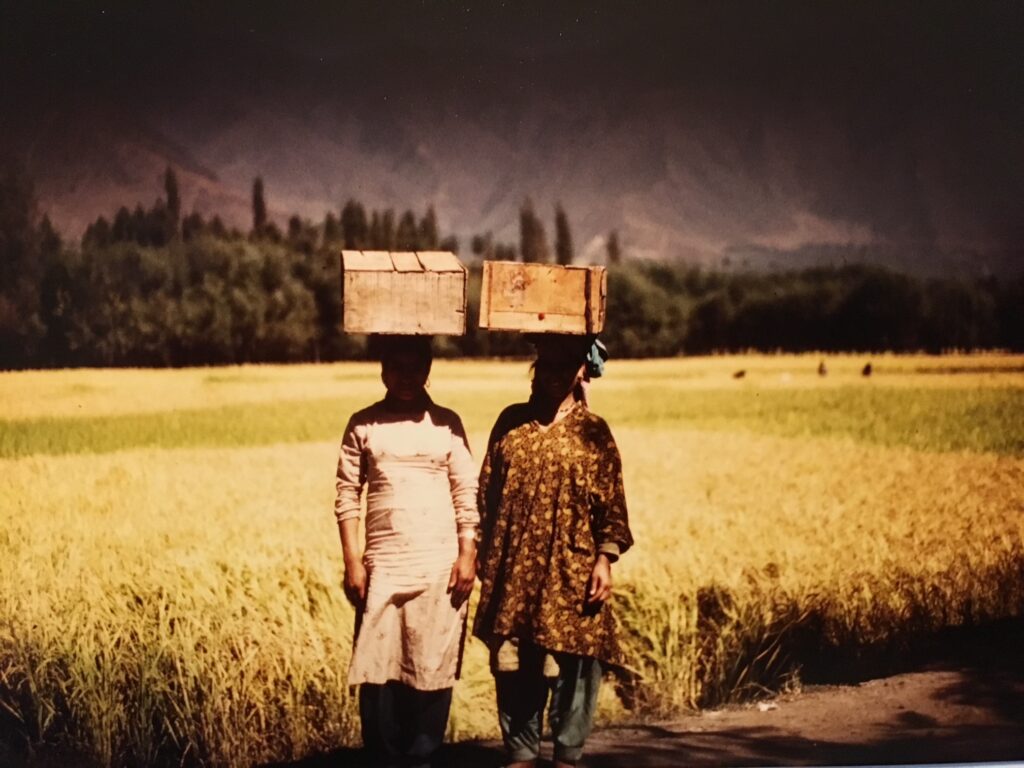

Finally arriving in Srinagar, a Muslim-majority city, I meet Fayez, a kind local who invited me to stay with his family. Their warmth was balm after the chaos. His family were papier-mâché artists, crafting intricate Russian-style nesting eggs. Fayez helped me find a tailor to replace the clothes that I had lost in Amsterdam. A flood had swamped my apartment there and I had few items left to wear. The locals treated me like royalty; their hospitality possibly tied to U.S. support for Afghan fighters against the Soviets. I felt welcomed, even celebrated.

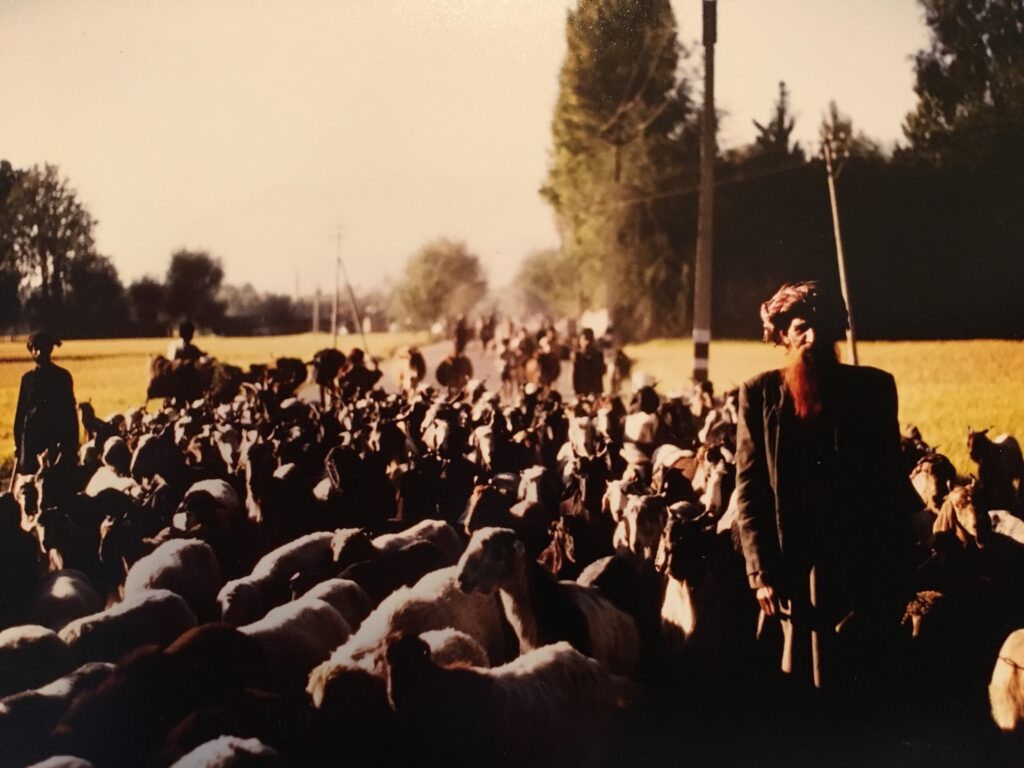

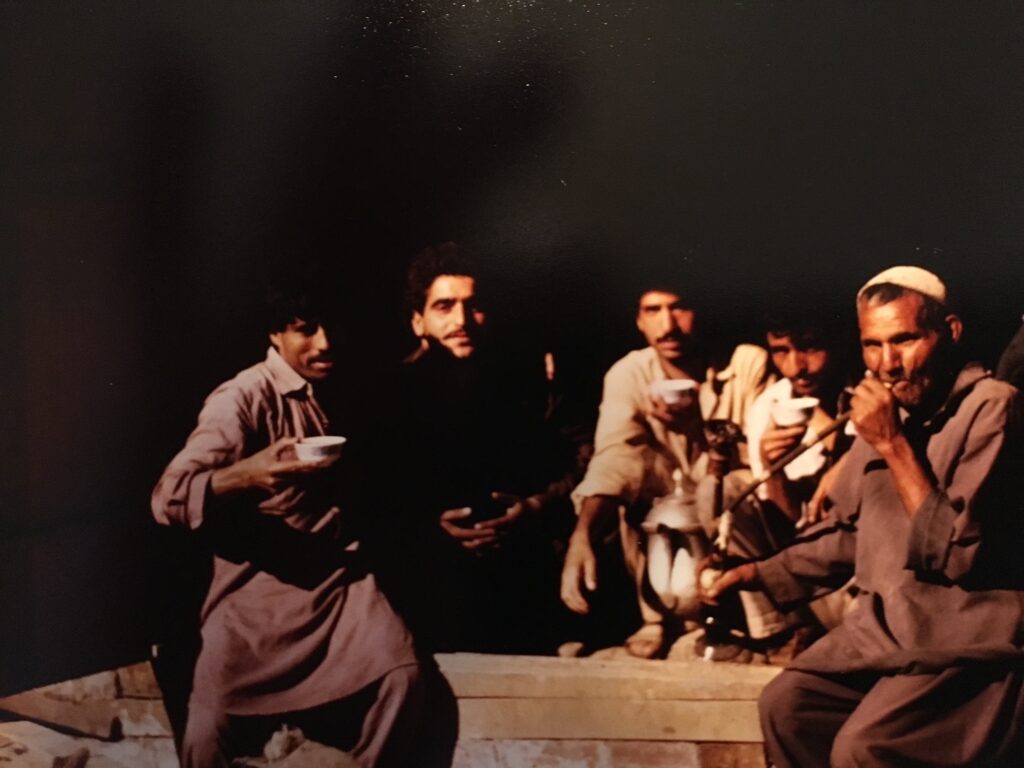

I explored Srinagar’s houseboats and the Himalayas. The 9th highest mountain in the world, Nanga Parbat, can be seen in the distance. I hiked the Liddar Valley and visit many villages. In one, I smoked Afghan hash with a local, easing my altitude adjustment. In another, I witnessed a baby goat’s birth, celebrated with goat milk and cookies. In Pahalgam, I savored pumpkin, rice, and chai during a festive holiday. For the first time, I slept soundly, my body relaxing in the clean, serene environment.

Reflections and Return

After a week of relaxing, I prepared to leave for Agra to see the Taj Mahal. The journey to Kashmir was exhausting, often terrifying, but unforgettable. The people’s kindness stood out against the backdrop of poverty and danger. I looked forward to returning someday on board their new train, not the bus. Ironically, this year of 2025, after 40 years of construction, India opens the tallest train bridge in the world that goes to Kashmir. It is India’s greatest engineering marvels. I anticipate that it will be a spectacular ride that will rival the Swiss Alps.

For the continuation of this journey see previous “Way Down Upon the Ganges River, 1987″

All photos from author except where noted.

About the author:

Fischer’s adventures continue: 2024 motorcycle trip through Vietnam, followed by summiting Mt. Lassen, CA shortly after.

Gene Fisher, known in Santa Cruz surf circles and Tahoe and Jackson Hole ski areas as “Tarzan” (for self-explanatory reasons), is a world traveler and adventurer.

Fischer is the owner of Mobile Climb USA, an interactive entertainment team-building company (www.goclimbawall.com) and free-lances as an independent business development consultant.

He has also continued his passion for helping young people, reported a Carmel Pine Cone newspaper feature on Fischer. “He has coached kids in just about every sport, and has served as a Boy Scout leader and YMCA leader. ‘Life is good,’ he said. ‘Life is grand.’