“The Subterraneans” movie scene, based on Kerouac’s novel. Starring George Peppard and Leslie Caron, and Kerouac credited as screenplay co-writer, 1960.

Bohemia by the Bay

Looking back on the ‘Beat Generation’—the creative, non-conformist spirits of the mid-century and their haven by the Bay. (Originally published 2016)

Story: Jeff Kaliss, Poetry Editor

On the 60th anniversary of writer Jack Kerouac’s coinage of ‘the Beat Generation,’ aficionados of mid-century California could look back on how culture has a way of playing out differently on the frontier, where things look different, and even sound different. For more than three centuries, San Francisco and the Bay Area have functioned as a frontier for the rest of the nation and the world.

In the middle of the last century, in the atmosphere of relative comfort and complacency that followed World War II, San Francisco began gathering creative, non-conformist spirits from the opposite coast, where the 26-year-old Kerouac had come up with a concept of the ‘Beat Generation’ in 1948.

Rejecting some of the core values of mainstream America, Kerouac applied his new term to a breed of ‘new vision’ poets and authors whom he encountered in New York, including literary friends Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and later Gregory Corso. And in the decade that followed, he migrated with most of them westward.

In the homey setting of San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood, fueled by good Italian deli food, coffee, alcohol, marijuana, and an assortment of other uppers and downers, the poets and authors fused with musicians, visual artists, thespians, filmmakers, and other free spirits to form a free-flowing group which San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen dubbed ‘Beatniks.’ They spoke the lingo which had been catalogued by jazzman Cab Calloway in his “Hepster’s Dictionary” of the previous decade. Living in modest “pads” and on little “bread”, these “cats and kittens” found expression in art and on musical “axes”.

As with the gold-rushing Forty-Niners of a century earlier and the Hippies of a decade later, the Beats generated legends about their lifestyle, which in turn attracted many more would-be participants from far and wide, while strengthening the group’s cultural influence.

“I got a kick out of the counter-culture atmosphere,” recalled Ned Eichler, who got to sample it in North Beach while working for his father’s firm, Eichler Homes, before and after his stint in the Army in the early 1950s. “There was part of me that identified,” he continued, “and the great thing about the Beats was, they didn’t insist that you had to be like them.”

Eichler developed an affinity for some, but not all, of the modernist modes of expression associated with the Beats in poems and novels. But he felt less in tune with their embrace of modern jazz, avant-garde painting, and experimental film, casually hip clothing, and a non-traditional approach to sexual and social relationships.

Some of these affects helped open minds and tastes for what was to come, with the Hippies, the Punks, and other subcultures in the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond.

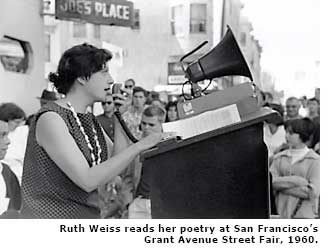

The (now late) poet, playwright, and filmmaker ruth weiss, called by some the ‘Goddess of the Beat Generation,’ was one of the survivors, keeping the Beat spirit alive in appearances around the world. Having escaped Germany and the Nazis with her family as a child in 1933, weiss later divested her name of capital letters (in rebellion against her native tongue) and spent her teens and early 20s discovering America.

“And I ended up in San Francisco, right in North Beach, ‘cause I knew it was a Bohemian section,” said weiss, when I interviewed her as a spry 80. “I mean, Steinbeck and Saroyan…used to hang out at the Black Cat [on nearby Montgomery Street].”

Like many of the gathering Beats, weiss took on a variety of jobs in the 1950s, including posing clothed or nude for the city’s growing number of art students. She read her poems publicly alongside Madeline Gleason, who’d started San Francisco’s first poetry festival in 1947. She also frequented performances by jazz artists, with whom she’d previously kept company in Chicago and New Orleans.

A saxophonist boyfriend, weiss said, “really taught me to open my ‘third ear’” to the sounds of the postwar form of progressive jazz called bebop, or just bop. And then I was writing, and it was just the same kind of rhythm.” Another musician coaxed weiss into reading her poems with jazz accompaniment. She went public with this performance at North Beach’s Cellar club in 1956, creating a fusion of forms that became a trademark of the Beats.

Musician Larry Vuckovich showed up on the same scene after emigrating with his family from the Montenegro region of the former Yugoslavia. Studying music during the day at San Francisco State College, Vuckovich became a night owl in North Beach, where he could dig the jazz jam sessions and rub elbows with his college teacher, John Handy, and his private tutor, pianist Vince Guaraldi, who was a resident of the neighborhood. Though still acquiring a new language and not that attracted to poetry, the young bebopper could understand the mutual attraction of musicians and wordsmiths.

“The poets were hip, they wanted to be current with creative development—so sure, they went to jazz,” said Vuckovich, (then) 72 and living in Sonoma County. “And of course, you had great literature, films, and everything. They all were trying to express the feelings of life.” Vuckovich also enjoyed what he recalled as “the great experience” of interpolating jazz sets with appearances by Lenny Bruce, one of the quick-witted, confrontational comedians booked in the ‘50s and ‘60s at North Beach’s legendary venues Off Broadway, the Jazz Workshop, and the hungry i.

For those who experienced it or wish they had, the elements of Beat style have in our present day taken on the nostalgic glow of artifacts, celebrated and exhibited in a much-changed North Beach: at City Lights, the Columbus Avenue bookstore established in 1953 by (now late) poet and mentor Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and at the much younger Beat Museum, which opened in recent years around the corner. At age 90, Ferlinghetti still lived in the neighborhood, not far from his shop and from several extant Italian delis and cafes that still provided him with “stuff that you can’t get anywhere else.” City Lights Books continued to publish a periodic Review and both new poetry and verse from his long-ago Beat buddies, many of whom are now deceased. (Editor note: Ferlinghetti died at 101 February 22, 2021)

Vuckovich and weiss revived the well-remembered joining of jazz with poetry in a joint performance at Kimball’s East, in the East Bay. With Ferlinghetti, they were part of the ongoing excitement of the Bay Area, whose musical, literary, and other artistic expressions have expanded well beyond North Beach, continuing to challenge and change the aesthetics and attitudes of the rest of the world.

From the Bay Area base line, let’s revisit a dozen of the most prominent road markers of the Beat Generation—special people, places, and things that, a half-century ago, helped inspire and sustain San Francisco’s Beat identity.

Meet the Beats

- Lawrence Ferlinghetti / City Lights Books. In Larry Keenan’s cover photo for the erstwhile City Lights Journal, proprietor Lawrence Ferlinghetti is pictured standing in front of the North Beach bookstore of the same name, brandishing an oversized umbrella above some of San Francisco’s Beat and post-Beat cognoscenti. No matter that it isn’t raining; the photo symbolizes the tall, mannerly Ferlinghetti’s protective and supportive attitude towards the city’s creative souls, persisting more than half a century to the present day.

Studying in Paris in the 1940s, Ferlinghetti, an expatriate New Yorker, had acquired an interest both in literate, user-friendly bookstores and in the city of San Francisco, as it was represented to him by older poet Kenneth Rexroth. Early in the following decade, Ferlinghetti relocated to North Beach and, with pioneering pop culture magazine editor Peter Martin, opened City Lights Books, in 1953, as the nation’s first paperback bookstore.

After Martin sold out to Ferlinghetti in 1955, the latter expanded into publishing, with a book of his own verse, like him measured and elegant, that launched City Lights’ ‘Pocket Poets Series.’ A year later, he published Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg, which bourgeoned both his and the poet’s fame. The paperback, flying in the face of establishment propriety with its unabashed use of language and images, landed Ferlinghetti in a nearby municipal court, as a defendant against obscenity charges.

City Lights Books continues its functions as a center for readings, publications, book sales, and the cordial continuation of the best of the Beat spirit.

- Jack Kerouac. From Massachusetts and New Jersey, respectively, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg met in 1944 while attending Columbia University in New York. There, with the older St. Louis-bred writer William Burroughs, they began a celebration of rebellious words and deeds, which eventually led to their joint migration to the West Coast a decade later.

Personifying the wanderlust of his postwar peers, Kerouac spent time at sea and on a number of road trips (eventually reaching San Francisco), in the company of hard-knock but fascinating characters. One such acquaintance was New York junkie Herbert Huncke, from whom Kerouac borrowed the word ‘beat’ to apply to the contrarian lifestyle to which he and his friends aspired.

All these experiences, and more to come later, were grist for Kerouac’s writer’s mill, resulting over two decades in numerous poems and novels, the most famous of which is On the Road. Lodging in San Francisco or its suburbs, Kerouac became a staple of the North Beach Beat scene, dying sooner than most of his friends (in 1969, of cirrhosis at age 47) and posthumously lending his name to the alley alongside City Lights Books.

- Allen Ginsberg. Son of a mother committed to an asylum, Allen Ginsberg was subject to periods of blazing energy and depression. As a teenager, Ginsberg was relieved to find himself in compatible company, both intellectually and creatively, in New York City’s mid-1940s.

There, Ginsberg wrote for a Columbia student newspaper; hung with Kerouac, Burroughs, and future Beat bard Gregory Corso; and in 1954 followed the path of some of these friends to San Francisco, where he initiated a romantic relationship with his fellow poet and eventual life-long companion, Peter Orlovsky.

Ginsberg’s poem Howl gained notoriety after prompting a much-publicized obscenity trial, but it wasn’t the only work in which the poet made reference to homoeroticism and other sexual matters, which he believed were deserving of full expression in literature and elsewhere.

In poems and publicly, Ginsberg also expressed his dismay at his country’s crass commercialism and at the lack of understanding and mistreatment of mentally unbalanced persons, including his mother, himself, and patients he’d encountered in hospitals.

Ginsberg’s expository style was sometimes suggestive of the title of his most famous poem, seeming like a run-on howl composed of repeated words, coinages, and fantastic images, though all this is also reflective of his ethnic grounding in the literature of Judaism.

After the Beat era, Ginsberg remained a familiar figure in San Francisco and other progressive locales, protesting war and advocating for gay rights and the legalization of marijuana.

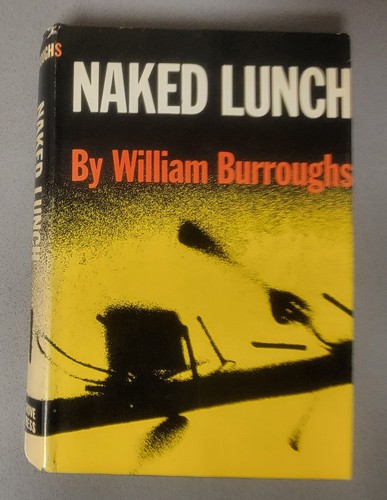

- William Burroughs. Older (born in 1914) and usually better dressed (in suit and fedora) than his fellow Beats, William Burroughs made for a curious sort of mentor to several of the younger Beats, and to many other writers and readers of his several novels in subsequent generations.

Perhaps not evident in his demeanor, Burroughs’ homosexuality and long experience with guns, heroin, and pills were transparent in his writing, which often functioned as thinly disguised autobiography.

Burroughs’ books, including the celebrated Naked Lunch (1962), also referenced the quirky circumstances of his life, including his sometime employment as an exterminator, an unintentional act of manslaughter, and his seamy sojourn in North Africa. His honesty in expression, like fellow writer Neal Cassady’s, helped set a standard for the Beats, as did his exploration of America’s underworld.

But it was Burroughs’ erudition that first made an impression on the teenaged Allen Ginsberg when they were introduced near Columbia in the mid-‘40s. Ginsberg soon shared his acquaintance with another new friend, Jack Kerouac, but Burroughs didn’t follow the two younger writers west until well after their instigation of the Beat culture in San Francisco. Ginsberg and Kerouac, however, championed Burroughs on the West Coast, and later spent time with him in Paris and in Tangiers.

By the 1990s, Burroughs had seemingly surpassed the status of other Beats as a pop icon, appearing in films directed by Gus Van Sant and receiving the adulation of younger icons David Bowie, Patti Smith, and Johnny Depp.

- Michael McClure. The Six Gallery in San Francisco’s Marina neighborhood, west of North Beach, was a memorable site for Michael McClure to render the first public reading of his poetry, in October 1955. New to the city, to which he’d come to study art with abstract expressionist Clyfford Still, McClure had been asked to assemble a reading at the Gallery, a former garage that had become devoted to the visual arts.

McClure enlisted his new friend, Allen Ginsberg, to help recruit poets, who included Philip Whalen, Gary Snyder, and Philip Lamantia, with elder poet and long-time San Francisco resident Kenneth Rexroth functioning as emcee. The event is best remembered for Ginsberg’s introduction of his long, passionate poem Howl, cheered on by an inebriated Jack Kerouac. McClure’s own first book of poetry was published a year later, and he went on to produce many others, suffused with his animalistic approach to the human condition. (He considered people to be “bags of meat” and performed one of his readings for the lions at the San Francisco Zoo.)

Despite this call to the wild, McClure had a benign nature that was easily embraced, in the latter part of the ‘60s, by the Hippies. Like Ginsberg, McClure stood up to authorities, who accused him of depicting obscene acts in his play The Beard.

McClure served as playwright-in-residence at San Francisco’s Magic Theatre, penned the song ‘Mercedes Benz’ (made popular by Janis Joplin), and was acknowledged as a poetic mentor to Doors songwriter Jim Morrison. (Editors note: McClure later collaborated with Doors keyboardist Ray Manzarek.)

- On the Road. Jack Kerouac wrote his chef d’oeuvre, On the Road, in 1951, before the acknowledged emergence of the Beat culture, and set the start date of the narrative in 1947. But the incubation of the Beats was already in process by the earlier date, with the coming together in New York City of Kerouac, fellow writers Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, and the charismatic soldier of fortune, Neal Cassady. The foursome is featured in the Viking Press first printing of On the Road (1957) under fictitious names.

Despite the pseudonyms (which incidentally weren’t used in Kerouac’s original manuscript, typed over a period of three weeks on a continuous scroll of tracing paper), many of the novel’s events were based on the real-life experiences of Kerouac and his friends and acquaintances that took place during the period that the Beat culture was coalescing.

The book’s title references four journeys made by Kerouac across the U.S. and Mexico, some in the company of Cassady. Cassady inspired Kerouac not only as a vital fellow traveler but also because of his own literary style: natural, without traditional literary affect, and forthright in recounting sexual adventures.

Although some of the racier episodes and the real names of the protagonists were edited out by Kerouac before the initial publication, they were mostly restored, 38 years after the author’s death, for The Original Scroll edition of the book, published in 2007.

Still, enough salaciousness remained in the first published edition of On the Road in 1957, along with accounts of a marijuana-fueled foray into Mexico, to garner plenty of positive and negative reactions from Beats and the wider reading public. The book helped reinforce images of the Beats in general, and San Francisco (one of the featured locales) in particular, and was enormously influential on later writers.

- Howl. Arguably the most widely recognized poem from the Beat era, and an enduring landmark in 20th century American literature, Howl was revised several times by its creator, Allen Ginsberg, right up to the point of his first public reading of it at San Francisco’s Six Gallery in 1955.

Ginsberg had written the long poem at his cottage in Berkeley at the urging of his therapist and of his poetic mentor, Kenneth Rexroth, while devoting himself to writing full time and striving to free his voice. He found models of expression in William Carlos Williams and in his fellow New York expatriate Jack Kerouac, but set out to create his own form of versifying, based on the repetition of key words and the basing of line lengths on the rhythms of breathing.

This incantatory form, somewhat evocative of Jewish liturgical text, supported the content of Howl, which bemoaned the repression of a variety of counter-culture characters. In one of the poem’s four sections, Ginsberg, inspired by an episode of peyote-fueled visualization, rails against the monster of contemporary materialism.

During the Six Gallery reading, the poets and others who were assembled recognized the passion and uniqueness of Ginsberg’s vision, as did Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who set about publishing Howl and Other Poems, and a reporter from the New York Times, who gave the poem national exposure.

The objects of Ginsberg’s empathy and criticism resonated with the Beat Generation, several of whose prominent figures appear within Howl, often in coded references. Peppered with homoerotic and other sexual allusions, Howl gained further fame as the subject of an obscenity trial, at which Ferlinghetti prevailed.

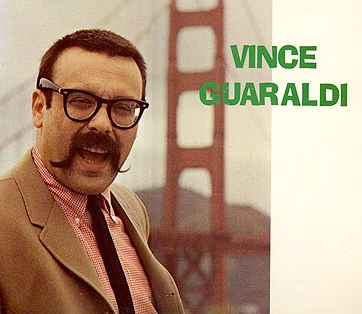

- Vince Guaraldi. “Jazz didn’t need any poetry,” maintains jazz pianist Larry Vuckovich. “It was poetry in itself.” But in the 1950s, jazz was happening in the same environs as poetry, in North Beach, where one of the neighborhood’s most distinctive-looking musicians, the mustachioed Vince Guaraldi, became the young Vuckovich’s piano teacher.

“San Francisco in the ‘50s covered the whole [musical] spectrum,” Vuckovich remembers, and Guaraldi’s keyboard and compositional style embodied several genres: cool phrasing, Latin syncopation, and a light-hearted approach to voicings evocative of country player Floyd Cramer.

Hard-bop players were closer in rhythm and spirit to the written language of the Beats, but the denizens of North Beach frequented clubs where Guaraldi worked his smoother stylings. They also caught him in the company of Latin leader Cal Tjader, who launched Guaraldi’s recording career and employed him throughout the ‘50s, until the pianist left to focus on a solo career. Guaraldi also appeared elsewhere in San Francisco, sometimes engaging Vuckovich as a ‘sub’ or as a partner in dual-piano gigs.

The breezy classic, ‘Cast Your Fate to the Wind,’ from Guaraldi’s 1962 album Impressions of Black Orpheus, brought him a jazz Grammy and crossover placement on the pop charts.

A couple of years later, Guaraldi secured another long-term gig, scoring a series of television productions and a full-length film based on California cartoonist Charles Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip. The pianist’s sweet ‘Linus and Lucy’ theme for Peanuts brought him the greatest renown and fame, long outlasting his premature death at age 47 in 1976.

- Mort Sahl. Credited as one of the forefathers of contemporary stand-up comedy, Mort Sahl could be more accurately tagged as a comic social commentator, an important subset of the stand-up panoply.

Born in Montreal and brought up in Southern California, Sahl came north in the early 1950s to Enrico Banducci’s hungry i nightclub in North Beach to hone his chops. Newspaper in hand and casually dressed in a pullover sweater, he’d comment sardonically on current events, especially politics.

“[Sahl] was just so charming,” recalled Catherine Munson, then a young married biochemical researcher and soon to become the first lady of sales for Eichler Homes. “We were heavily involved in the politics and excitement of change, so we thoroughly enjoyed Mort.”

Despite his rather academic appearance, Sahl’s mordent political criticism resonated with the anti-authoritarian attitude of the Beats. And though he lacked the self-deprecating insight of Woody Allen and the risqué blue humor of Lenny Bruce, Sahl was much revered by contemporary and later comedians; in fact, Allen compared Sahl’s influence on comedy to Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker’s on jazz. Sahl was also befriended by several American Presidents, recorded a dozen albums (including one at the hungry i), and appeared in several films.

- Lenny Bruce. The hungry i, along with other North Beach venues, also helped spotlight the stand-up comedy career of Lenny Bruce, whose approach shared Sahl’s criticism of the establishment but differed distinctly in Bruce’s use of character voices and confrontational profanity.

Bruce’s spontaneous, inspired, sometimes eccentric riffing was in fact much closer to the spirit of bebop than was the smooth, reserved demeanor of Sahl. “I preferred Bruce to either Allen or Sahl, because Bruce was more biting,” said Ned Eichler. “But my parents just didn’t take to him. They liked Woody [Allen] and the folksingers.”

The law’s surveillance of Bruce’s material for obscenity was more pernicious than that suffered by the Beat poets, who were of course drawn to Bruce’s club appearances on both coasts. Bruce was in fact arrested several times, and ultimately died of a morphine overdose while awaiting appeal on a workhouse sentence.

Among Bruce’s San Francisco fans was newspaper columnist Herb Caen, who dubbed him “a rebel, but not without a cause.” Bruce recorded some of his overdrive schtick for Fantasy, the Berkeley-based record label, and remains a role model for practitioners of ‘blue’ stand-up comedy.

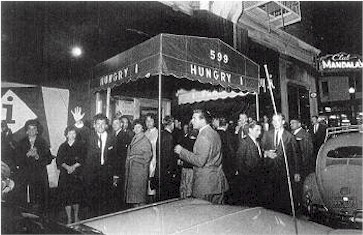

- hungry i. The brick-wall décor duplicated in stand-up comedy clubs across the nation is said to have originated at the hungry i, the venue opened by colorful North Beach impresario Enrico Banducci at 599 Jackson Street, after he’d purchased the enterprise with a hip and mysterious name in the mid-‘50s from its previous owner, Eric ‘Big Daddy’ Nord.

Interspersed with the comedy of such critical minds as Mort Sahl, Woody Allen, and Lenny Bruce was live music from national touring jazz and folk acts. The Kingston Trio recorded at the club, as did the Limeliters, musical satirist Tom Lehrer, and Mort Sahl. As its national reputation grew, the hungry i also helped boost the careers of comedians Bill Cosby, Godfrey Cambridge, and Professor Irwin Corey, as well as neighborhood resident Vince Guaraldi.

It is said that Banducci bowed to the pleadings of a very young Barbra Streisand, granting her an extended booking in the late ‘50s that served as her steppingstone to national fame.

By dint of the cutting-edge comedy in particular, and despite its relatively sophisticated setting, the hungry i attracted Beat audiences as well as such local cognoscenti as the young Ned Eichler and his parents.

By the mid-‘60s, with stand-up and folk less in fashion, Banducci had decided to sell the club and concentrate his efforts on the café that still bears his given name, at 504 Broadway.

- The Cellar. The reputation of this little venue at 576 Green Street preceded its opening in the heart of North Beach in 1956, with crowds five times the 100-person capacity soon clamoring to get in.

Sometimes called The Jazz Cellar, it had been converted by jazz musicians Wil Carlson, Jack Minger, and Sonny Nelson from an old Chinese restaurant into one of the city’s best-loved showcases for bebop and progressive music. This alongside the nearby Jazz Workshop, the Black Hawk in the Tenderloin district, and a few venues further west in the Fillmore and Richmond districts.

A week after opening the nightclub, Nelson invited a friend, the 26-year-old poet ruth weiss, to read her work with jazz accompaniment. It was a hit—and a draw for Beat audiences seeking late-night entertainment, as well as for such aspiring bebop musicians as the young Larry Vuckovich. “Then I started asking other poets to come and join me,” weiss recalls, “none of who ever gave me any credit, and some who became very famous.”

Veteran poet Kenneth Rexroth picked Lawrence Ferlinghetti, still relatively unknown for his verse, to partner with him in a live recording at the Cellar on the Fantasy label, accompanied by the ‘Cellar Jazz Quintet.’ Jack Kerouac professed his love for The Cellar in his writing, extolling “the girls with dark glasses and blonde hair, the brunettes in pretty coats by the side of their little boy (The Man)—raising beer to their lips, sucking in cigarette smoke, beating to the beat of the beat of Bruce Moore, the perfect tenor saxophone…”

END

A museum where the Beats live on

The Beat Generation continues to carry on its rich legacy in the heart of San Francisco’s North Beach—thanks to Jerry Cimino, the nouveau-Beat entrepreneur behind the neighborhood’s fascinating Beat Museum.

In 2006, a half-century after it began to thrive, Beat culture became enshrined at 540 Broadway Street, around the corner from the landmark City Lights Books. The Beat Museum’s grand opening featured readings and recollections by Beat icons Michael McClure and Al Hinkle as well as John Allen Cassady, son of the late Neal and the surviving Carolyn Cassady.

Under the direction of Cimino, the venue has since continued to regularly host celebrations of poetry and prose by visionary writers dead and living.

In keeping with dioramas found at other kinds of museums, there’s an evocation, particularly on the upper level, of a lived-in 1950s Beat pad, with furniture, fixtures, and a typewriter of that era. Bop and West Coast ‘Cool Jazz’ burbles in the background.

Individual exhibits showcase such landmark works as Kerouac’s On the Road and Ginsberg’s Howl, and enlarged photos of Beat luminaries adorn the walls. Supplementing City Lights’ holdings, a vast collection of books of Beat literature, poetry, and culture (as well as of the Hippie and rock cultures that followed) are for sale. There are also audio and video recordings, posters, postcards, and the like.

Cimino and his staff are fabulously knowledgeable and friendly. Check them out at kerouac.com and 1-800-KER-OUAC. And continue to follow the Beat to Hippie journey at Camino’s new Counterculture Museum in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury.