A(nother) Metaphysical Movie Review

By Robert V. Tobin

There is no such thing as simple national origin story, which always involve complications, controversy and chaos. In addition to winning a battle or birthing a country, they also reveal next steps in civilization’s evolutionary cycle. Realities of everyday life are rarely revealed in binary us-against-them analyses, and never in those involving military engagement. Myths and misperceptions form a ‘fog of war’ that distorts any attempt to make sense of it all afterward.

“The American Revolution” is Ken Burns’ latest (and first) chapter in our country’s formation saga. Twelve hours long, it seems as much an ordeal to endure as the war itself. Released before the 250th anniversary of our Declaration of Independence, his documentary depicts our earliest attempt to address a continuing challenge: how to balance unity and freedom.

If Burns is right that its national parks are America’s best idea, resolving this quandary remains its most pressing concern. In anticipation of this anniversary, his film allows us to review the personal, communal, national and international implications of its founding, both then and now.

INTIMATE INDEED

One reason Burns’ work is subtitled an “intimate history” is the multiple, sometimes incestuous relations among the rebels, loyalists, native tribes, Africans, English, French, German and eventually Spanish participants in this dispute. Sometimes thin, often shifting lines between them led to a ferocity that heightened residual bitterness among both winners and losers of these confrontations. Regional differences further divided rebels, causing General Washington to continually admonish his soldiers to consider themselves Americans rather than Virginians, New Yorkers, etc. Imagine how different it would be today if Democrats and Republicans heeded his request.

A second reason for this “intimate history” is the nature of war itself. When hand-to-hand combat is its determining factor, victories are fleeting and subjugation only temporary. As areas deemed pacified became cauldrons of renewed violence, war sometimes became murder. Justice, a battle cry of this struggle, was selectively applied; Burns tells us of patriots mutinying for lacking food, clothing and pay going unpunished in Pennsylvania, but executed in New Jersey.

A third reason this is an “intimate history” is because war’s finality is as personal as it gets. Nearly seven thousand American revolutionaries were killed in action, and twice as many died of typhoid, small pox, influenza and other battlefield diseases. Comparable casualties among the British included former friends turned sworn enemies. Young men coming of age desiring to fight for their country had to decide: which one?

BIRTHING PAIN(S)

Neither this nor any other people’s revolt ever achieved full-fledged citizen governance, if you go by Webster definition of democracy: “an organization or situation in which everyone is treated equally and has the right to participate equally in management, decision-making, etc.” That’s why Burns’ documentary closes with a quote from Dr. Benjamin Rush, a Founding Father who declared as the war ended: “… the Revolution is not over.”

Since some states would not approve the U.S. Constitution as written, its ink was barely dry before being amended ten times by the “Bill of Rights.” These were written by James Madison, later our fourth president, who saw this document as nothing more than “a draft of a plan” for adapting existing practices to unforeseeable developments. Benjamin Franklin voiced qualified approval, “with all its faults.” Thomas Jefferson warned against allowing its guidance to become rigid and unchangeable.

Burns bemoans today’s tendency to glorify and even deify our country’s Founding Fathers. Too often, he finds, they are depicted as wise philosophers in wigs reaching consensus on the issues of the day. In fact, willingness to sacrifice individual benefits for collective advantages was no greater then than now. Their various affiliations made agreement difficult and compromise inevitable. This tale would seem farfetched had it happened elsewhere, and remains as pertinent today as it was compelling then. In Burns’ retelling, it becomes something most rare: television worth watching.

SUSPENDED DISBELIEF(S)

It’s hard to believe the military phase of our nation’s birth lasted seven years (1777 to 1782). Even harder to believe is that it took another five years to forge agreement among thirteen independent entities about what their victory meant. Half of the participants in those deliberations came directly from battlefields where they defended principles not fully articulated, and definitely not yet agreed upon. According to Alexander Hamilton, these leaders’ primary aim was to avoid their greatest fear: an “unprincipled man” seizing power and becoming a demagogue. They had learned first-hand that societies not governed by ethical principles and the will of the majority default to policies based upon might-makes-right and end-justifies-the-means. Notably, they were less concerned about another maxim (those-with-the-gold-make-the-rules), since that’s who they were and what they were doing.

Few recognize the beginning of their demise, and even fewer then believed an empire would be undone by its own arrogance. Disparaging what they did not understand, British leaders forgot how initial success creates a false sense of progress, or how quickly disdain breeds resentment. These tendencies predisposed them to dismiss the power of an idea whose time had come; their country’s erosion of world dominance over the next two centuries began at that moment.

Even so-called “rebels” had trouble believing in their own army, as it was so lacking in soldiers, guns, bullets, food, pay, clothing, shoes, tactical expertise, and combat success. They forgot it is possible to lose every battle and still win the war when properly prepared and positioned for the ultimate confrontation. “There is nothing like a common foe to unite previous enemies,” Burns observes, but “the war bringing these colonies together led to a peace which threatened to tear them apart.” Subsequent imposition of taxes and other early assertions of federal authority drew protests suppressed firmly and violently – the very reaction that caused Americans to revolt in the first place over the same complaints still reverberating today.

COMMONALITIES

Burns also shows how much our first war was like all others. Neither side attained all promised benefits, making it harder to justify miseries suffered by both. Each side saw the other as uncivilized, uncouth and unworthy of respect or consideration. Both knew God was on their side, even though Abraham Lincoln noted the impossibility for any deity to be “both for and against something at the same time.”

Most combatants were jobless, landless, ordinary citizens defending rich property owners who, with rare exception, exempted themselves from enlistment. Seeming successes often involved costly blunders attributable as much to ignorance as hubris made by leaders quick to claim credit in victory and blame others for defeat.

And, as in all wars, this one had heroes and villains … sometimes in the same person.

- Benedict Arnold was among young America’s most accomplished generals until offering the British a key fort on the Hudson River (West Point).

- The richest American at the time, Robert Morris, helped finance a Revolution he profited from immensely by intermingling personal and public funds in speculations on war supplies.

- Washington’s precedent in relinquishing power – first militarily, and later politically – is widely considered his greatest accomplishment; nearly as remarkable was his perseverance despite shortages in men, material, and morale – the last of these including his own. Burns and others believe his eventual success was due to more capable generals, and his decision to ruin Native Indian settlements via habitat destruction normalized a policy of genocide pursued throughout the following century.

IRONIES ABOUND

Delegates to America’s first Continental Congress had no template to follow in a world ruled up to that point by monarchs and bandits. They worked to differentiate state from federal powers, create co-equal branches of government and define monetary policies, all while managing a war and forging foreign alliances. In the process, their attempts to define ‘the public good’ became mired in political disputes and personal quarrels. “Articles of Confederation” serving as an interim platform for resolving inherent conflicts failure to do so; this sowed seeds for America’s second uncivil war fought seven decades later among ‘unionists’ and ‘confederates’ still arguing over the line between local and national jurisdiction.

Awakened by what Burns considers “a wanton abuse of power,” the patriots’ rebellion launched a de-colonization process triggering liberation movements worldwide, starting with the French Revolution (1789). America’s subsequent interventions in other nations’ affairs have not always advanced the same freedoms for their citizens our forebearers fought and died to provide us.

Freedom of religion was among the earliest attractions of those drawn to America. But this was found no truer among the hundreds accused, dozens convicted, and nineteen executed during the Salem Witch Trials (1692-93) than the Pennsylvania Quakers whose pacifism subjected them to property confiscation and exile in the late 1770s. Others finding more rhetoric than reality in such promises included Jews aboard a ship denied permission to dock in U.S. ports after fleeing Nazi Germany (1939), and Muslims deprived of travel visas in the late 2010s.

Thomas Jefferson, designer of America’s small government structure, expanded its scope by doubling the nation’s geographic size through the Louisiana Purchase (1803). His model was never adjusted to accommodate an eventual eight-fold increase (275 million to 2.3 billion acres) in administrative responsibility due to additional territories attained through the Texas Annexation (1845), procurement of the Oregon Territory (1846), the Mexican Concession (1848), the purchase of Alaska (1867), and the coup giving America control of Hawaii (1893).

Most ironic, Burns says, was having “all men are created equal” proclaimed by Jefferson and fought for by Washington, some of America’s largest slave owners. These champions of liberty insisted Africans emancipated during the war be returned; it was the British who persevered in their commitment to grant slaves their freedom, and who abolished slavery altogether three decades before Americans again fought each other over the right to perpetuate it.

EPILOGUE

Democracy, Burns concludes, requires an engaged citizenry to keep its governance process vibrant.

His exposition of our country’s origin story reminds us that contention is not only inevitable, but also healthy and helpful if maturely handled. Dissent is a source of strength in the American playbook, not an indication of weakness or cause for demonization.

Like all art, Burns’ film helps us to clarify our thoughts and feelings. This allows us to more calmly express our own opinions about what matters most, and better hear other citizens doing the same.

Citizens’ responsibility to do so is what our American Revolution was – and continues to be – all about.

Robert V. Tobin is the father of four, stepfather of four, and grandfather of eleven great people brightening prospects for a world founded upon trust, optimism and compassion.

A(nother) Metaphysical Movie Review

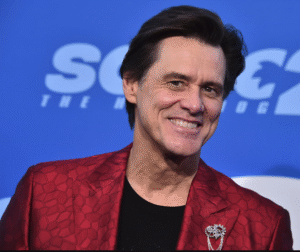

The Evolution of a Funny Man: Jim Carrey

from Robert V. Tobin

*********************************************************************************************************

One professional hurdle shared by actors of all kinds: the difficulty in moving from one modality to another after being typecast in a particular genre.

Comedians struggle most in this regard, deemed natural rather than skilled at what turns out to be the most difficult acting job of all. They also face another obstacle: nightclub lifestyle hazards which make “making it big” a longshot at best. These combine to make a comedian’s career similar to a Middle Ages peasant’s: cold, hard and short.

Initially rejected by both The Johnny Carson Show or Saturday Night Live, Jim Carrey squeezed stand-up dates between lackluster movies for a dozen years before becoming the only major actor on all five years of In Living Color (1990-94). This led to outlandish comedic roles in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective, The Mask, and the aptly named Dumb and Dumber, all landing in 1994.

Thereafter, he made the leap from slapstick to thoughtful movies more pertinent and prophetic today than in the years they were made.

This transition began with Liar Liar (1997), a tragic comedy about a lawyer whose habitual deceit of himself and others nearly ruins his work and family life until he discovers honesty really is the best policy. This film dramatizes how situational ethics and selective truthfulness undermine clear thinking and mutually beneficial decision-making. Absence of these is concerning in any era, and increasingly so today.

Carrey’s range of talents became unignorable the following year when he won a Golden Globe Award (Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama) for The Truman Show in 1998, whose exploration of the influences of perspective on perception anticipated the expansion of Reality TV beyond its Candid Camera roots. A year later, he earned another Golden Globe Award in the opposite category (Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy) for his sensitive portrayal of Andy Kauffman in the biographical dramady Man on the Moon (1999).

Subsequently, Bruce Almighty (2003) previewed what might happen if the Higher Power – played by Morgan Freeman – gets tired of all our complaining and puts someone else in charge; Carrey’s character uses newly acquired omnipotence to advance selfish interests until realizing the value of empathy. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) dives deeply into dilemmas arising in romantic partnerships. 2008’s Yes Man (based on a real-life memoir by Danny Wallace) presented an only somewhat lighthearted account of the debilitating nature of lethargy with its underlying pessimism and the inertia which results—noting enroute the possibilities and pitfalls of self-help strategies for their alleviation.

The Majestic arrived in 2001 amidst this exposition of life challenges, entwining the personal with the universal in a manner entertaining, educational, and even encouraging.

Carrey’s role personifies some of the screenwriters accused of being a communist in the 1950’s. Some indeed were informed advocates of Russia’s radical adaptation to economic problems sweeping the world in the early 20th century. Many were simply curious about alternatives to capitalism after its shortcomings were exposed by The Great Depression at the end of the Roaring Twenties. A few, like this movie’s Peter Appleton, went to these public meetings find a romance partner. All were exercising their constitutional right to learn about a country which became our ally in World War II.

When an unproven hindsight allegation took away his job and girlfriend, Appleton flees Hollywood – an act that could indicate guilt or desperation. He is taken to the nearest doctor after being found wandering a coastal beach when a car accident leaves him with amnesia. This lands him in a small town suffering the same post-war tragedy sustained by countless others around the globe after losing many – and, in some cases, most – of their young men in far-away battles.

The town’s mayor, sheriff, doctor, and eventually even Appleton himself become convinced of what they all desperately wanted to believe: that he is Luke Trimble – a local hero still missing-in-action nine years after WWII ended. Trimble’s father and girlfriend lead the jubilation ensuing as at least one of this town’s gone-but-never-forgotten men seems to have finally found his way home.

Celebrating this restoration, Appleton’s new family revives a long-deferred plan to rejuvenate their community’s sole movie theater – The Majestic, where local residents formerly gathered before being overcome by sadness. Everyone joins together to bring it and, by extension, their community and country back to their former glory. Describing all three, Luke’s father s intones: “In a place like this, the magic is all around you. The trick is to see it.”

That magic becomes even more elusive as these three subplots collide upon discovery of Appleton’s damaged car, alerting investigators from a congressional committee on “unamerican activities” to the whereabouts of this suspected communist just as his amnesia starts to recede. Today’s viewers of this movie are hard-pressed to ignore its foretelling finale, as politicians manipulate processes and coerce confessions to advance their own agenda. Their violation of the Bill of Rights tramples “truth, justice, and The American Way,” the closing line of every mid-Fifties Adventures of Superman television episode even as those values were being corroded by McCarthyism.

Not until three decades later would we recognize Appleton and the town’s residents were experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which made them even more prone to entanglements of Sociogenic Illness, also known as mass hysteria. The latter can spread through any group experiencing excitation, loss, or alteration of function (Psychiatry Journal – 2016). Both synergize each other, enmeshing questions of character and culpability as community members individually and collectively strive to heal from successive shocks to their mind, body and spirit.

This movie also displays a third communal ailment known today as ‘gaslighting,’ as commonplace in the 1950s as in 2001 when The Majestic opened while national support was being mustered for wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. In both eras, citizens’ own sanity, their neighbor’s motivations, and their leaders’ veracity were being questioned when anything less than unquestioned acceptance of questionable information was demonized as unpatriotic.

As film critic Roger Ebert noted at the time: “There could have been no hint of the tragedy of Sept. 11” while The Majestic was being made, but the movie “is uncannily appropriate” two months later upon its release. He found it to be a stark contrast to the end-justifies-the-means style of patriotism promoted in the Rambo movie franchise and elsewhere around that time. This explains The Majestic’s largely negative reviews, which were contradicted by Ebert’s conclusion that it “… expresses a faith that our traditional freedoms and systems are strong enough to withstand any threat, and that to doubt it is – well, un-American.”

Like all great entertainers, Jim Carrey’s lifetime of work presents us with a mirror that allows us to look within ourselves for humanity’s most treasured assets: honesty, humility, accountability, adaptability, kindness, optimism and commitment. He helps us more easily and clearly see these by helping us find the humor in it all as well.

At its best, entertainment sheds light on the challenges of Real Life unfolding in Real Time. Perils of the unfortunate, prosecution of the innocent, and perseverance required of those pursuing long-term gains rather than short-term benefits – these are timeless themes of those responding to this industry’s highest calling over the last two millennia. Ancient Greeks and Romans, Shakespeare and Moliere, George M. Cohan and Lin-Manuel Miranda, and so many others use formats ranging from situation comedies and costume dramas todepict obstinate obstacles to personal development. Their efforts to correlate message and method have become ever more daunting as their mediums become increasingly beholden to the highest bidder in these days of mergers and acquisitions.

May they continue doing their best to be their best, inspiring the rest of us to do the same.

The End

More Metaphysical Movie Reviews:

A(nother) Metaphysical Movie Review

By Robert V. Tobin

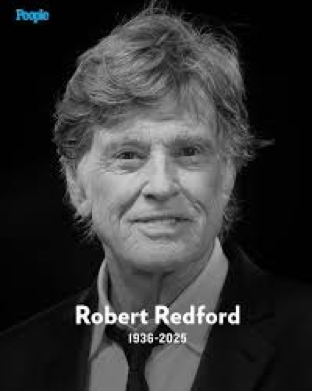

EPITAPH

Almost no one is in favor of racism, sexism, misogyny or homophobia, and even fewer want polluted air or water.

Loud complaints alleging nefarious Hollywood bias in such matters raise a question: is it the complainers or entertainers who are out of touch with their audience?

Robert Redford devoted his career to answering that question. This former Marin County (Tiburon) resident would have remained in obscurity if his artistry and agenda were incompatible with consumer tastes and interests. His productions’ cash receipts indicate otherwise: $3.1 billion domestically and $6.6 billion worldwide, placing him among the Top Ten in producer, director and various acting roles.

The basis for this disparity between rhetoric and reality is conveyed in a recent New York Times column by Republican pollster Kristen Soltis Anderson (8/29/25). Her data finds just one-quarter of American voters ‘strongly liberal’ (13 percent) or ‘strongly conservative’ (11 percent), placing a veto-proof majority in the middle ground on social and fiscal matters. Anderson’s conclusion: “… the political center today is less a point on a spectrum and more of a mind-set, an openness to weaving together a worldview with various strands from right and left — paired with a belief that, as broken as things are now, there is hope they can get better in the future.”

These findings concisely encapsulate the evolution of Redford’s lifelong attempt to balance concern and optimism while holding unswerving light on life’s darkest, most daunting subjects.

His early career found this pretty boy seizing many opportunities but taking few chances, and perhaps wisely so. It is now hard to imagine him between 1960 and 1964, slogging through nearly thirty appearances in TV shows such as Perry Mason, Dr. Kildare, The Twilight Zone and The Untouchables. Three more years were absorbed by forgettable movies with such apt titles as Situation Hopeless – But Not Serious (1965) and This Property Is Condemned (1966).

His later career choices sometimes leaned toward cheesy roles implying commercial rather than artistic aims. But his judgment was on target regarding typecasted starring roles: even as he was struggling to find work, he was smart to refuse ill-fitting opportunities in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and Bonnie and Clyde (1967), as well as later films like Star Wars (1977).

Immediately thereafter, Redford became bankable thanks to back-to-back blockbusters – Barefoot in the Park (1967) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1968). These gave him leverage to serve as producer for the first of nearly sixty movies and documentaries unlikely to come to viewers’ attention otherwise. The Candidate (1972) depicts inexorable compromises imposed by our country’s electoral process just as its leaders were becoming impeachable, developments he documented for posterity in All the President’s Men (1976) even as pressure was already mounting to forget that painful saga’s sordid details.

Immediately thereafter, Redford became bankable thanks to back-to-back blockbusters – Barefoot in the Park (1967) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1968). These gave him leverage to serve as producer for the first of nearly sixty movies and documentaries unlikely to come to viewers’ attention otherwise. The Candidate (1972) depicts inexorable compromises imposed by our country’s electoral process just as its leaders were becoming impeachable, developments he documented for posterity in All the President’s Men (1976) even as pressure was already mounting to forget that painful saga’s sordid details.

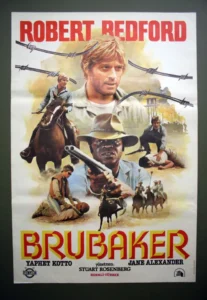

In more than fifty subsequent movie roles and ten turns in the director’s chair, Redford’s continued exploration of the body politic proved equally clairvoyant. Domestic security concerns were examined in Three Days of the Condor (1975), Sneakers (1992), Spy Game (2001), Lions for Lambs (2007) and The Company You Keep (2012). Interplay between power and corruption in our prison system was scrutinized in Brubaker (1980) and The Last Castle (2001). Unflinching portrayals illuminated the pervasiveness of graft in the early days of television – Quiz Show (1994) – and in the real estate development industry – The Milagra Beanfield War (1988). Influences on the news media were brought into focus in Up Close and Personal (1996) and Truth (2015). Remnants of colonialism provided the backdrop for Out of Africa (1985) and Havana (1990). The process by which national crises beget mass hysteria giving rise to obstruction of citizens’ right to due process was the focal point of The Conspirator (2010).

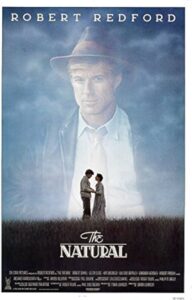

As he matured, Redford’s work reached beyond the political to the personal. A deep dive into the family trauma of suicide earned him a director’s Oscar for Ordinary People (1980). Inconveniences of aging were the subtext of The Natural (1984), An Unfinished Life (2005), Our Souls at Night (2017) and Old Man and the Gun (2018). Other resonant themes included immoderations of wealth: The Great Gadsby (1974) and Indecent Proposal (1993); the consequences of crass consumerism: The Electric Horseman (1979); the pertinence of life’s metaphysical dimensions: The Horse Whisperer (1998) and The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000); a worst-case retirement scenario: The Clearing (2004); and the physical, mental and emotional obstacles to remaining unflappable as life’s storm waves crest: All is Lost (2013), where, as the movie’s sole character, he spoke almost no words.

Redford’s movies and documentaries celebrating nature’s wonders are too numerous to mention; prominent among the former are A River Runs Through It (1992) and A Walk in the Woods (2015). Interest among Northern Californians and others in Saving the Bay (2009), a three-part environmental series he narrated, generated the highest rating of any PBS program on the evening of its initial broadcast.

More lasting impact came from his launch of Sundance Institute and its annual Film Festival. More than eleven thousand artists since 1981 – now 1,400 annually – are supported in the development of their skills and presentation of their work in film, music and live theatre mediums. The Institute’s Native American and Indigenous Film Program tells stories otherwise silenced. Redford himself mounted several made-for-TV movies from Tony Hillerman’s compelling books about the intricacies of law enforcement on the Navajo Reservation – Skinwalker (2002), Thief of Time (2003), Coyote Waits (2003), and, in his final work product, the multiple episode series Dark Winds (2022-2025).

As personal, professional and political identities increasingly intertwined, his daring choices carried viewers to the precipice where problems and solutions uncomfortably interact. His message in any of these capacities was always simple and even conservative: life can be cold, hard and shorter than we wish. It requires elevation of long-term gains over short-term benefits, and the patience, persistence, and courage to act in accordance with abiding ideals. It necessitates a refusal to accept neither of the lesser of two evils, and a commitment to remain calm and clear when considering their alternatives – especially as animosities emerge.

Perhaps Redford’s greatest acting job was in role modeling a form of leadership whose only real test is followership. He did this in a manner rarely seen today: confident but not cocky, critical but not disparaging, aspirational but also realistic. In the process, he proved it was possible to avoid personal scandal in a profession awash in it. And, even while acknowledging the impracticality of Mother Nature’s complete protection from the world’s vagaries, he put his money where his mouth was by prioritizing stewardship of precious resources we were blessed to inherit and are now challenged to pass along unfouled to our children’s children. Such dogged pursuit of incremental progress moved us closer to a better tomorrow.

A favorite quote from T.S. Elliot – “There is only trying. The rest is none of our business” – was chosen by someone born into the depths of The Great Depression who worked his way to the top of a business unaccustomed to the determination, diligence, and dignity he brought to it.

Robert Redford left that industry stronger and this world better than he found it. And so, as Charles Dickens wrote about reformed Scrooge: “… may that be truly said of us, and all of us!”

END

Robert Tobin is the father of four, stepfather of four, and grandfather of eleven great people

brightening prospects for a world founded upon trust, optimism and compassion.

Original “The Graduate” poster signed by Dustin Hoffman.

A(NOTHER) METAPHYSICAL MOVIE REVIEW from Robert V. Tobin

MOVIE: “The Graduate” (1967)

DIRECTOR: Mike Nichols

SCREENPLAY: Calder Willingham & Buck Henry

LEAD ACTORS: Dustin Hoffman, Anne Bancroft, Katherine Ross

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Robert Turtees

SOUNDTRACK: Simon & Garfunkel and Dave Grusin

A new season of school commencement exercises prompts a look back at how “The Graduate” predicted many aspects of America’s future.

Rife with outstanding performances, this film presented a new generation of creative talent. Dustin Hoffman’s movie debut attracted the first of seven Academy Award nominations for Best Actor; he has been awarded two thus far in a lifetime of acting achievements. Mike Nichols earned the Academy’s Best Director honors, making him one of few entertainers receiving an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony award – the last of these an incredible eight times for classic Broadway shows ranging from “Barefoot in the Park” and “The Odd Couple” to “Annie.” The prominence of Katherine Ross’ role led to her casting as the third star in “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” Anne Bancroft returned to limelight after previously winning an Oscar for her role as “The Miracle Worker,” the young teacher – legally blind herself – who helped Helen Keller learn to communicate despite being unable to see, hear or speak. Simon & Garfunkel’s path to supergroup status was accelerated by three Grammy awards for the movie’s soundtrack.

This prescient coming-of-age story introduces us to a young man burdened by the expectations of those confined by traditions and taboos largely unspoken but strictly enforced. When college provided neither a compass nor map for his transition into the Real World, Benjamin Braddock had numerous offers of assistance thrust upon him – in one case literally.

Interplay between comedy and tragedy crystalizes when a friend of Braddock’s parents propositions him while her husband is arranging a date with their daughter. One of the film’s iconic lines – “You are trying to seduce me Mrs. Robinson … Aren’t You?” – is among the top 100 quotes in cinematic history. Power disparities, toxic jealousy, overbearing and/or undermining parents, and debilitating secrets all come to the fore in this cautionary tale.

“The Graduate” marked a new phase in theatrical exposition of relations between older women and younger men. Other contemporary examples extend from the platonic (“Harold and Maud”) to the sensual (“Summer of 42”). More recently, Angela Bassett (“How Stella Got Her Groove Back”), Jennifer Lopez (“The Boy Next Door” and “The Mother”), Emma Thompson (“Good Luck to You, Leo Grande”), Anne Hathaway (“The Idea of You”) and Nicole Kidman (“Babygirl”) explored the possibilities and pitfalls of such interactions.

Rupert Murdock, Bill Belichick, and so many other men face no stigma for their embrace of considerably younger partners. Octogenarians such as Al Pacino and Robert De Niro barely get a raised an eyebrow for fathering children with woman decades younger than themselves. Leave it to the French to reverse this double standard, as Bridgette Macron is widely credited with guiding her husband’s political ascendence. But Emmanuel Macron is not the first president to marry his former school teacher, having been preceded in this distinction by Millard Fillmore – America’s 13th president (1850 to 1853).

Another aspect of this movie’s foreshadowing: the privileges made accessible to many – but not all – Americans thanks to opportunities for educational advancement and wealth accumulation triggered by the technological revolution following World War II. The G.I. Bill and a progressive tax structure inhibiting billionaire-hood fueled unprecedented economic growth that carried the middle class to its highpoint just as this movie was released.

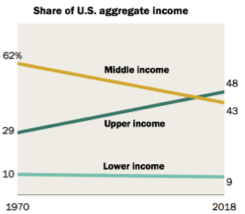

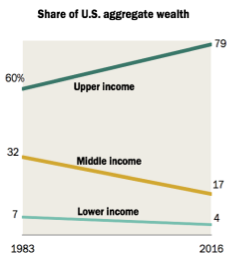

Immediately thereafter (from 1970 to 2018), according to a Pew Research Center study in 2020, American middle income households’ share of aggregate income dropped from 62% to 43% while upper income households’ share rose from 29% to 47%, a trend continuing since then. In this same timeframe, aggregate wealth of upper income households rose from 60% to nearly 80% while middle income households’ share dropped from 32% to 17%. The poor only got poorer during this period, with their share of total income dropping from 10% to 9% and their share of total wealth sliding from 7% to 4% in this same period. With the benefit of hindsight, it is clear those disparaging economic redistribution are the ones benefitting from its ongoing occurrence.

Two subsequent developments this movie did not predict: the Gig Economy launched by bootstrap entrepreneurs attempting to reverse this ever-widening financial disparity by working for Lyft, DoorDash, etc., and the driverless cars and semi-trucks that will soon destroy it.

This film’s most famous anticipation of emerging trends came in its single-word of career advice, as “Plastics” became another of the top 100 movie quotes of all time. The petrochemical industry, valued at $5 billion when this film was released in 1967, was already a major component of “the military-industrial complex” President Dwight Eisenhower waited until his last day in office to warn us about nearly a decade before. Sixteen presidents since then – as often Democratic as Republican – made only token attempts to corral what has since become an $820 billion monster which has nearly twice as many lobbyists as there are members of Congress.

It’s no coincidence the first Earth Day occurred just three years after “The Graduate” premiered. It took from then until now to realize recycling efforts worldwide have processed just nine percent of all plastics ever produced. The remaining ninety-one percent marinate in landfills and oceans to be inherited by countless future generations after having gifted each of our bodies – and theirs too – with as much as a credit card ‘s worth of microplastics.

“The Graduate” accurately depicts what was then viewed as a miracle product that will change lives in ways only now becoming clear. Plastics have become as ubiquitous as fast food and soda pop, the former now recognized as many times more lethal even as its production is being de-regulated while the latter attracts politicians’ faux outrage. If you think that has nothing to do with money and power, check out “Dark Waters” (2019) or “The Insider” (1999). These two too true stories raise troubling questions about the lack of personal liability of those responsible for deliberate and sometimes deceptive corporate actions with fatal consequences for others and billions in profits for themselves and their investors.

Watching our children and grandchildren, nephews and nieces graduate from their schools over the next few weeks makes one wonder whether their world will change as much … and little … as Benjamin Braddock’s.

_________________________________________________________________________

More METAPHYSICAL MOVIE REVIEWS from Robert V. Tobin

THE CHOSEN

DIRECTOR & PRODUCER: Dallas Jenkins

ACTORS: Jonathan Roumie, Elizabeth Tabish, Shahar Issac, Paras Patel, Vanessa Benavente, George H. Xanthis, Noah James

PRODUCTION COMPANY: 5&2 Studios

In its 5th of 7 seasons, with 40 episodes currently available.

Many welcome Passover, Ramadan, or the Lenten/Easter season as an opportunity for reflection and healing. Like every cinematic entertainment, several recent films documenting various aspects of this occasion require suspension of disbelief. Their actors are not actually who they pretend to be; the story does not always unfold exactly as things occur; and their conclusions may not be what we expect, wish, or are prepared to process. Yet their medium, to paraphrase Marshall McLuhan, conveys their message.

Productions with numerous episodes over multiple seasons present additional challenges. Patience, endurance and discernment are not cultivated by a world unfolding in momentary flashes. As the thinnest of threads connecting the past and future, the present moment is well suited for quick appraisal but affords little chance for contemplation … let alone revelation. Assertions of the miraculous demanding a faith contradicted by fact constitute further reason to avoid such programming altogether.

These factors made it likely not many would watch “The Chosen,” and that even fewer would accept its invitation for introspection. Yet this production achieved remarkable success by pioneering a unique crowdfunding model attracting $10 million to its first two seasons, and ever onward thereafter. The production’s fifth season, premiering in movie theaters recently and via streaming next month, continues to examine circumstances surrounding the arrival and departure of Jesus through the eyes of those who knew him best – his disciples.

The list of others similarly challenged by his message is not a short one. Episodes introduce us to the High Priests who long predicted imminent arrival of exactly such a messiah, but somehow certain this one wasn’t it. The ruling Roman elite and their minions are shown striving to preserve their lifestyle by perpetuating the lifecycle of the fading empire empowering them. The disgruntled populace squeezed between these competing forces fervently anticipate arrival of a military as much as spiritual savior who would vanquish their nemeses.

Factual accuracy was not the primary goal for gospel writers of this era, theologians’ ongoing arguments notwithstanding. New Testament authors instead sought to illustrate lessons hard to grasp and difficult to abide; vividly illuminate pitfalls best averted at a time when education – let alone social media – was unimaginable; and promote values and practices fostering collective coherence in chaotic circumstances.

Historians find evidence confirming existence of this man about whom everything else has been argued vehemently and often lethally ever since. This continuing debate about who he was detracts from what he said; this includes: extending loving kindness to everyone, regardless of whether they deserve it; helping those who need it, especially those who make us uncomfortable doing so; turning the other cheek, extending forgiveness 70 x 7 times if necessary; judging not, that we not be judged; and treating others the way we want to be treated, and not the way they treat us. There is no more radical an agenda.

Given how much of Jesus’ energy was devoted to admonishing people to wake up, it is ironic some now deem being “woke” the harshest of criticisms. The one thing he said more than any other – fear not – constitutes an admonition hardest to apply when most pertinent. He saw how our wants blind us from seeing we already have what we need; it is our vulnerabilities and insecurities that tell us otherwise, pushing us toward what used to be called the “Devil’s Playground” before our culture’s de-mythification process took over.

Within this parable about parables, its most famous is most applicable currently. In response to a skeptic’s inquiry as to who is one’s neighbor, The Good Samaritan story uses a foreign adversary to suggest compassion be applied on the basis of need, not nationality, ethnicity, religion, societal, financial or legal status (Luke 10:29-37). Jesus’ conclusion – “go and do likewise” – prescribes a set of actions, but also an attitude which removes a distinction between insiders and outsiders that separates ‘us’ from ‘them’.

Differing views about what did or didn’t happen before and after Jesus’ death ought not detract from a message as revolutionary today as it was resisted two thousand years ago. The question of whether this story is literally or metaphorically true sidetracks us from the only real issue: whether we are willing to remove any impediments to loving kindness from our thoughts, words and actions. A big ask indeed.

Jesus found the greatest of sins rooted in the hypocrisy of self-righteousness. He bemoaned those proclaiming adherence to principle while hiding their pursuit of wealth, power and privilege. Even if only metaphorically, New Testament’s stories warn about temptations imbedded in the road to success; conflation of loyalty with allegiance, and silence with consent; propensity for betrayal to come from within, sometimes conveyed by a kiss; difficulty discerning between our lower and higher selves; and dangers of conjuring an illusion of crisis to justify actions unconscionable if not illegal.

Like the ancient texts on which it is based, “The Chosen” says as much about the disciples of Jesus – then and now – as it does about him. Both face difficulty understanding anything that cannot be comprehended, and reluctance in accepting that which is not already agreeable. Its most recent episodes warn viewers of dangers arising whenever people believe to be true whatever they currently think, then selectively apply principles and practices to advance individual interests at the expense of The Greater Good. Watching the early apostles grapple within themselves and among each other while confronting such challenges makes it impossible to see this as a tale about days long past.

Still pertinent is G.K. Chesterton’s acerbic observation a hundred years ago: “… the Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting; it has been found difficult and left untried.” Like those of the past, loudly self-acclaiming Pharisees today intertwine religion without compassion with governance without democracy. Although our country was largely monocultural and monotheistic at its beginnings, the founders anticipated hazards when intertwining governmental power with religious authority. Their first amendment to a freshly minted U.S. Constitution made explicit protections for freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and petition, yet the demonization of dissent is as dangerous now as it was deadly for Jesus then.

The recurring nature of these challenges makes this an enduring story well worth retelling, and rehearing.

Those who disparage two millennia of reverence for a liberator advocating good works as the cornerstone of good living are hard-pressed to explain today’s wild popularity of superheroes, Marvel-related and otherwise. These latter-day saviors are celebrated for helping the helpless and restoring hope to the hopeless who, polls show, constitute a growing majority of our population. Small wonder so many are so enthused by someone telling them: “you are the light of the world … don’t hide it under a basket” (Matthew 5:14-16).

“The Chosen” reminds us not to do that to ours.

END

PREVIOUS METAPHYSICAL MOVIE REVIEWS

from Robert V. Tobin

TWO MOVIES: “Black Bag” & “No Other Land”

In “The Celestine Prophecy” as well as in quantum physics, it is suggested that what we perceive as coincidence or serendipity is actually synchronicity.

This conclusion is less ignorable after seeing “Black Bag” and “No Other Land” on the same weekend when a New York Times op ed column* acknowledged the Covid virus originated in a Wuhan bio-lab.

“Black Bag” is a spies-spying-on-spies thriller unfolding in the current-day. It studies how personal interests intertwine with institutional investments and international intrigues to produce effects completely un-anticipatable and potentially devastating. I leave it to you to see how that turns out, and instead highlight its underlying – pun intended – cautionary tale about how secretiveness fertilizes the seedbed in which the likelihood of deceiving oneself and others grows ever larger.

Those in the so-called “intelligence” community are admonished not to tell even their own spouses where they’re going or what they’re doing, keeping all such information hidden in their ‘black bag.’ This not only gives the movie its title; it also exposes the outer limits of a shared human aspiration: complete freedom. This film’s protagonists eventually find the apparent advantages of unaccountability are accompanied by a loss of genuineness that exposes vulnerabilities at life’s surface and inhibits experiences of richness at its depths. While often seemly ill-advised, this movie reminds us that honesty really is the best policy in personal, organizational, and international relationships. Commitment to its value shapes the morality which assures it.

The consequences of such scruples’ absence are vividly illustrated in “No Other Land.” This documentary introduces two young journalists living a half-hour apart and a world away. One has no voting rights and zero mobility while living under military law; he is one of countless Palestinians being forcibly displaced by expanding Jewish settlements. The other has voting rights and unrestricted travel privileges while living under civil law; this Israeli is one of hundreds of thousands of protesters in his own country and millions around the world who condemn antisemitism without endorsing Zionism and defend any nation’s right to self-defense while opposing the genocide of its declared enemies.

Jiggling hand-held camera shots, dramatic in-your-face confrontations, and quiet conversations convey a West Bank Palestinian community’s experience in the decades before October 7, 2023, when Hamas terrorists killed 1,189 Jewish concert goers, injured more than 7,500, and kidnapped 215. Seeing that horrific attack as unconscionable is just as important as understanding it did not arise out of nowhere.

Exactly where is this “other land” to which they were being asked to relocate, asks a mother whose son has just been shot by soldiers waving demolition notices for homes bulldozed even as new construction permits elsewhere were being denied and building tools seized. Equally poignant was the young Israeli’s increasing helplessness in quelling his Palestinian collaborator’s hopelessness as their efforts to mobilize public concern fail to ease legal indifference and military intimidation. Desperation erodes trust and allegiance among friends, and leads to bad decisions among enemies.

Learning about this dilemma is easier said than done, with news media subject to bias and this film not yet having a national distributor or streaming outlet even after winning an Academy Award. Its only available tickets at a small East Bay cinema on a rainy Sunday afternoon matinee were in the front row. Upon entering the crowded theater, we found younger, middle age and older Palestinians constituted most of the audience; I had never seen so many women wearing the hajib. Theirs and other attendees’ silence during and after this show was deafening, as we all quietly contemplated the ramifications of dislocating a culture several millennia old.

As they talked among themselves outside the theatre afterward, I wanted to say something … anything … to express regret for my country’s provision of the explosives that imploded their lives. But, as frequently happens when most applicable, saying “sorry” felt so inadequate I avoided doing it knowing full well any accountability evaded was my own. No doubt they are safer here than there but surely, they too must wonder what “other land” they will move to if anti-immigrant rhetoric translates into deportation policies here and elsewhere.

As Elvis Presley observed (and later found out the hard way himself): “The truth is like the sun. You can shut it out for a time, but it ain’t goin’ away.” Both these stories underscore difficulties in choosing between short-term benefits and long-term gains. Either can be pursued, but not simultaneously. Each has advantages as well as drawbacks, the former usually more obvious than the latter and those more immediate coming from the most temporary, least renewable outside sources. When pursuing their attainment, information-sharing is selective at best; misrepresentation is in the eye of the beholder; and the preferred outcome often secured by the loudest arguer, biggest gun, and/or fattest wallet. Sometimes all three are required.

Reality imitated art when all these lessons came to life the same weekend in the aforementioned New York Times op ed column describing subpoenaed communication between researchers and bureaucrats conspiring to obscure origins of the Covid virus. Afraid the truth would give credence to legitimate concerns as well as wild accusations, they instead did the very thing for which they condemn their critics: interfering with the public’s right to know by lying to protect their work and the institutions supporting it. Worse, they deflected a deepening political divide to a later moment when its exasperation is now even more untimely. Worst, their ruse distracted attention to – and delayed remediation of – lax security measures allowing human exposure to this deadly pathogen in the first place. Advantages gained by such deception never last long, and are aways outweighed by their costs.

Rudyard Kipling advised: when “being lied about, don’t deal in lies or, being hated, don’t give way to hating.” Deviousness created the world of cold calculation and callus indifference depicted in both these movies, and also found whenever any end is allowed to justify its means.

END

*”We Were Badly Misled About the Event That Changed Our Lives” by Zeynep Tufekci, March 16, 2025.

_________________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________________

BLACK BAG is a 2025 American film.

DIRECTOR: Steven Soderbergh

SCRIPTWRITER: David Koepp.

ACTORS: Cate Blanchett, Michael Fassbender, Marisa Abela, Tom Burke, Naomie Harris, Regé-Jean Page, and Pierce Brosnan.

Running time: 133 minutes.

Robert Tobin is the father of four, stepfather of four, and grandfather of ten who brighten prospects for a kind and loving world

END

The Brutalist

Metaphysical Movie Reviews™ by Robert V. Tobin

2024 co-production (U.S., the United Kingdom, and Hungary).

Directed by Brady Corbet, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Mona Fastvold.

Cast includes Adrien Brody, Felicity Jones, and Guy Pearce.

Running time: 216 minutes.

In “The Stoic Challenge,” William Irvine describes ancient Romans’ proclivity to approach seeming impediments not as obstacles to avoid but rather hurdles to overcome.

A title like “The Brutalist,” and an overture, intermission, and epilogue extending three-and-a-half hours, gives this movie almost as many stay-away warnings as Academy Award nominations (ten).

But those who overcome such hurdles will find themselves intrigued intellectually, informed historically, and challenged spiritually by a production meeting the simplest, clearest definition of art: it makes us feel.

This film renders a florid fictional portrayal of truth(s) emerging when real people encounter harsh realities. There is an acclaimed architect separated from his wife and orphaned niece in midst of the Hungarian Holocaust. He makes his way to a Pennsylvania relative who is helpful until suddenly not. Similar ‘help’ is then provided by a highly successful neighboring businessman having all the good intentions by which the road to hell is paved. This family’s eventual reunion and ongoing survival are threatened once again by the same brutalizing fear-based hatred which initially divided it. Cumulative impacts on all involved forge an emotional toxicity which, as Mark Twain predicted, corrodes the vessel in which it is contained.

Atypical layout of the opening credits and disjointed introductory camera shots quickly dislodge any subliminal expectations about entertainment and storytelling. Inverted angles of the Statue of Liberty further dispel any similarity to typical self-congratulatory tales giving more prominence to locals’ hospitality than immigrants’ perseverance. From there, “The Brutalist” delineates a societal dilemma as hard to deny as it is easy to ignore.

Sporadic disassociation between audio and visual tracks mirrors the sometimes-rattling dimensions of Real Life, while continual flip-flopping of good/bad characters disturbs our left-brain’s proclivity toward consistent binary categorization. Late 1940s chamber-of-commerce videos are interspersed to celebrate not just a place to live, but also a way of life in which a proliferating middle-class masks growing disparity between rich and poor. These videos’ sunny disposition contrasts jarringly with the discontentment and disrespect this story’s ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ display toward themselves and each other.

All of this unfurls – or, more accurately: unravels – within the context of building construction using the architectural style for which the film is named. It is no coincidence Brutalism emerged in Eastern European countries during their foreign occupation after World War II, describing a design template of exposed structural components completely monochromic and unadorned. A common critique is the cold, dehumanizing effect of resulting facilities on interpersonal relationships foisted around and within them … and throughout this movie.

In “The Brutalist,” the past is prologue to a wide variety of present-day discombobulations. Among these: foreign dystopias in which home becomes horrific; myriad disruptions of involuntary displacement; self-deceptions justifying everyday deceits; conflicts triggered when both spouses are working; pain-relievers with consequences more problematic than the injuries they treat; and influences of class and culture that foster casual, often unconscious correlations between ethnicity, poverty, capability, and possibility.

Regarding the most prominent of these gulfs – migration, the lessons of an ancient empire are again advisory. In the second of his eleven volume “Story of Civilization,” historian Will Durant says the Romans built no border walls until they did no good. He finds this to be a consequence of history’s most recurring nightmare: the lean and mean always take over the fat and happy. “The Brutalist” puts us at the center of this ongoing epic battle in which winners and losers are difficult to differentiate.

At the end it becomes clear “The Brutalist” is not any single one of the narrative’s distinctive characters. Rather, it describes a way of being all of them – and us as well – can become ensnarled when good intentions get more attention than actual effects. The script’s stark depiction of barriers to communication with those we love makes even more ominous our difficulty connecting with those we don’t.

Like some great works of art, this one imitates life at its most profound and unnerving. The tale’s protagonists demonstrate a very human propensity described by every psychologist since Buddha, i. e. accusing others of that which we are most guilty. Their weaknesses, as Socrates observed, are their strengths taken to excess. Their tendency to react rather than respond in crisis situations reveals our psyche’s simultaneous inclinations toward dominance and brittleness. And their racism and sexism share a symptom in common with mental illness and alcoholism, all of which constantly tell us we don’t have it.

All dramas – comic or tragic – arise from people concurrently pursuing respective interests. No one, author David Deida notes, can protect us from the “necessary confrontation with reality” which results.

But this chance to witness the impact of global forces on small-town residents in the safety of our neighborhood theater, or in the comfort of our couch at home, may offer the nearest opportunity to see ourselves in others, and them in us.

This makes “The Brutalist” not so much a show to enjoy as an experience to be savored.

END

Robert Tobin has been playing with words and music for seven decades.

Robert Tobin is the father of four, stepfather of four, and grandfather of ten who brighten prospects for a kind and loving world